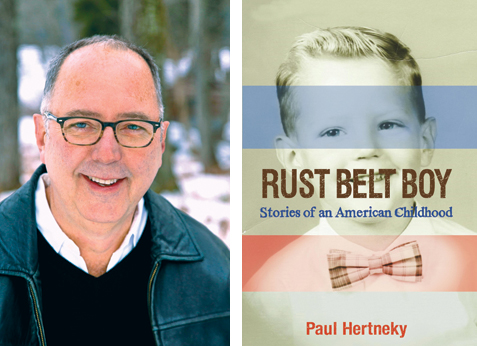

Rust Belt Boy: Stories of an American Childhood

By Paul Hertneky

The Prurient Power of Pierogi

In a place averse to looking back, cultural traditions in Ambridge emerged through religion, song, dance, and food. Mostly food, though, because every day when it hit the table it reminded us of our origins.

Housewives in the 1960s experimented with modern food, but they fell back on what they learned from their mothers. And the kitchens in church basements and parochial schools turned out some of the best Old Country cooking. For me, the melding of food and religion came together on meatless Fridays.

Sitting at a kitchen table my father had built, I picked up my bowl to finish the sweet brown milk left behind by the Cocoa Krispies, letting myself go cross-eyed, pretending I didn’t hear my mother click her tongue at my slurping. I stood up and set the bowl in the sink while checking the kitchen counter for my lunch box, and not seeing it. Oh, wow, it’s Friday, I thought when it hit me—no packed lunch today.

My father sat quietly, working his daily crossword, doodling profiles of beautiful women in the margins, his usual morning meditation.

“Dad, could I have some money for pirohi?” Not pierogi, which is what Poles and Croatians called the handmade, stuffed dumplings, served swimming in butter and onions. We Czechs and Slovaks had our own word.

Even though Milt would happily pay for my lunch, he insisted that I ask, as part of a larger lesson about money. “If you can’t ask for it, maybe you don’t need it,” he would say, explaining that when he went to the credit union or the bank for a loan, he had to ask; they didn’t just give it to him.

He smiled and dug into his front pocket, coming up with a fistful of change.

“How much?”

“Thirty-five cents.” Enough to feed a nine year-old.

He held out a calloused hand and reminded me to take enough for milk. “Sixty-five for me,” Mark said as he swaggered in. He was three years older. My father whistled low in mock-disbelief and snapped each coin on the Formica table one at a time. Betty jerked away from the counter where she had been buttering toast, annoyed by the snapping of the coins. Mark kissed her and she handed him a glass of grape juice. He downed it, grabbed the change and two slices of toast.

Watching quietly behind his empty bowl, Chris, who was just finishing first grade, looked up at Mark with wide eyes and announced, “Pirohi today!” Mark swallowed and said “Well, it is Friday, doofus.” With that, Betty, known for her prickly morning moods, popped Mark behind the right ear. He shook it off, and after a hurried round of kisses, we headed out the back door on a typical Friday morning, going off to school with more freedom than on the other days of the week. None of the Catholic schools provided everyday lunches, but their churches raised money with pirohi, or pierogi, or pirozhki. On Friday, without lunchboxes or bags, I had a free hand with which to gesture and swat, pick up pebbles and throw them at street signs, on our way to the bus stop.

Streets in the neighborhood ran like creeks to a river that was the main road. Out of the tiny households came kids with an array of European surnames: Marcia Sokil, with her fine and even Ukrainian features, would get off the bus at Sts. Peter and Paul; Dave Duplaga, a Pole, would say goodbye in front of St. Stanislaus, Bobby Cipriani at St. Veronica’s.

Swaying like a drunk around the corner, the bus skidded onto the gravel shoulder. It was a heap, an eyesore even in its industrial surroundings. Tosta’s Bus Company served the parochial schools, hauling their students in broken-down buses of two designs: the salvaged city bus, and the retired tour coach. The city buses, with fare boxes, shiny handrails, outdated billboards and cables for requesting a stop, were like rolling funhouses. In contrast, the coaches were dark and quiet, with overhead luggage racks and high, reclining seats that were threadbare and torn.

All the buses had rusty floorboards with holes big enough to see the road, but too small to lose a foot through, and gearboxes that just caught. The drivers, all mechanics, wore greasy jumpsuits and smelled like garlic, motor oil, and sweat. One smoked a pipe while he drove, stuffed with what could only have been plain old oak leaves.

“Oh…God…no,” I groaned when the door swung open and smoke rushed out like a late commuter. I saw the goofy smile of the green immigrant, holding the door lever with the same hand that held his goosenecked pipe, its mouthpiece crushed from his few remaining molars.

Inside, a cloud hung over the luggage rack. The usual choke of moldy seats and exhaust fumes that seeped up through the floor was overwhelmed by the smoldering trash in the driver’s pipe. We made gagging sounds and laughed, but the driver only watched us and smiled with his pipe in his teeth. Most days I prayed for the bus to break down. My hopes sprang from the frequency with which it happened—first a loud clunk, then a whimper from below, the driver cussing and wrestling the rig onto a lawn or a sidewalk. They never called for help, preferring to slide their toolboxes stored under their seat and fix it themselves.

On Fridays, though, my brothers and I wanted a smooth ride. By the time the bus wheeled to the curb in front of Divine Redeemer, I noticed Chris’s vacant stare and gaping mouth. The poor little aromatically sensitive guy, who ran from the house to escape offensive cooking odors, had turned khaki. I yanked our bookbags from the luggage rack and escorted Chris down the aisle and stairs. On the sidewalk, he doubled over and gulped the fresher air while I stood behind him, throwing my head back and inhaling like a hound in a stiff breeze. That’s when I caught it. The scent of Friday shot to my salivary glands. When two nuns pushed open the churches’ oak doors, even the latent incense gave way to the embrace of butter and onions.

During Mass, the promise and seduction became unbearable. My stomach clawed toward its quarry while I knelt through the long Latin consecration. I stared at the ornamental sacristy and my eyes glossed over, seeing Jesus feeding hordes of followers by multiplying pirohi instead of loaves and fishes. Or my gaze landed on the soft white mound of Monica Halicek’s top vertebra. How its contours transported me, how its roundness resembled a tender potato pirohi.

Rising for the Our Father, I examined my conscience for any transgressions that might keep me from momentarily stemming my cravings with the appetizer that was communion. The unleavened wafer seemed a poor substitute for the flesh it presumed to replace. A better choice, I thought, would have been a slice of pepperoni.

Friday mornings dragged. Through religion, geography, and history lessons, I learned only forbearance. Even the nuns admitted their cravings and their secrets for coping: muttering mantras like “Jesus, have mercy on me”—ejaculations, they called them (setting up real teenage confusion down the road)—until the moments of weakness passed.

Billy Evans poked me in the back while Sister Tomasina answered a knock at the door. “How many you gettin’?” he asked.

“A half dozen,” I whispered out of the corner of my mouth, careful not to turn around.

“I’m gettin’ a whole dozen.” Of course you are; you’re fat.

When noon arrived, Sister Tomasina opened the door and the full force of cooking odors washed over us. She cuffed her sleeves and folded her thick, hairy forearms as she stood in the doorway and watched the younger kids file toward the basement. I squirmed in my seat, fishing out the coins and slapping them on my desk for a final count. Satisfied, I cupped my hand at the edge of the desk and slid the coins into it, except for the nickel that bounced off my thumb and fell to the tile floor, found its edge and rolled all the way to the back wall, where it disappeared between a row of bookbags.

Billy noticed and we were both tracking the nickel when Sister Tomasina must have signaled the class to rise and form a queue. Caught by surprise, I spun and stood, tipping over my chair. While righting it, I turned to see the angry nun hustling toward me. Her black robes billowed like a crow descending on roadkill. She took me by the ear and dragged me, sidestepping, to face the blackboard two inches away. When I dared to look sideways, I saw Billy being flung ear-first to my side.

I closed my eyes and memorized the color of the bookbags the nickel had rolled between: red and powder blue. But I doubted I’d have a chance to retrieve it. I might end up staying at the blackboard throughout lunch. Sister Tomasina’s heart had long ago been removed, we theorized, frozen and broken into particles that, when added to torpedoes, made them more deadly. Maybe she’d let us go later, when the entire school had eaten the best pirohi varieties. Billy seethed. I would pay for this on the playground.

As our classmates marched out, the sweet aroma intensified and God’s own forgiving breath must have swept in and subdued the nun. She ordered us to catch up with the others, but before we escaped she drew a four-foot pointer from the folds of her apron and sliced the air behind us, cracking both of our buttocks simultaneously.

The sting made us hop. But we were giddy as we started down the stairs and Billy elbowed me hard enough to knock me into the rail. That was it; retribution delivered. He didn’t hold grudges. Besides, we were dropping into the most overwhelming sensual pleasure either of us would know until puberty, with a narrow escape behind us.

The pupils, as we were called, filed into a bright multipurpose room filled with long tables, folding chairs, and noisy pirohi hogs. This feast was open to the public, and local workers on their lunch breaks sat along the west wall. Kids filled half of the tables in the vast middle, and along the east wall, facing the room, sat a brigade of silver-haired grandmothers. They carefully spooned fillings—mashed potato, sauerkraut, cottage cheese, and lekvar, a prune preserve—into the disks of dough they cradled in their floury hands. They folded the edges together and pinched the semicircular dumplings into shape.

The pinchers would seldom rise. Other volunteers rolled out the dough and cut it into circles with teacups, or mixed fillings and delivered them to the pinchers in heaping bowls, then returned to harvest the finished pirohi.

Pinching and chatting in Slovak or Czech to the friends who flanked her, my grandmother, Anna Rosol, found my face and smiled, flashing perfect false teeth. I broke free of my classmates, now dazed in pirohi nirvana, and scrambled behind the pinchers—“Hi, Mrs. Hovanec, Mrs. Yaniga, Mrs. Duda, Mrs. Sinchak, Mrs. Tabachka”—until I reached my grandmother’s strong arms and soft cotton apron. She kissed me and hugged me hard, pressing her wrists into my back. Her hands, kept chaste for touching food, flew away from me. She was careful like that.

By now, Billy had reached the serving line and I had to hurry. I patted the coins in my pocket and sorely missed that nickel. I suppose I could have asked my grandmother for one, but I knew she was too poor. If she were to give it to me, she’d probably walk home instead of taking the bus. Still, the shortfall forced me to reconfigure my usual order, maybe cutting out the lekvar, its mellow sweetness made sophisticated when it met salt, pepper, butter, and onions. I hated quandaries such as these.

Just as I was about to pick up a plate, a hunchbacked woman in a dark print dress emerged from the kitchen lugging a giant bowl of snowy cottage cheese. She saw me at once, cried my name, and set the bowl down. She wiped her hands and grabbed my face, mashing a kiss on my lips before pushing me away and tugging at the ear still tender from my trip to the blackboard. Like a magician, she let go and presented me with a shiny quarter in the palm of her hand.

Grandma Hertneky, an osteoporotic angel, always greeted me in public with a gangway flourish—even though I saw her nearly every day. Her gypsy drama, in greeting, feeding, scolding, mourning, or scaring, never subsided. She counterposed Grandma Rosol, whose serene demeanor shrouded her in ethereal gauze.

Now I was flush. I knew all the ladies wielding spoons, too, and one scooped four glistening potato pirohis onto my plate. Then I boldly ordered two kraut to go with my usual two lekvar, forcing me to hold the plate with both hands. Searching for a seat, I saw Chris, nose-down, all business. I also spotted Mark, who had just cruised in with the upperclassmen and stood on his tiptoes to assess my plate, as if he might cross the room and steal it. He winked at me.

With the long-awaited aroma buttering my face, I found Billy and sat, just before my knees were about to buckle from excitement. I freed my fork from its napkin wrapper, grabbed the salt and pepper, checked the caps for cruel jokes, and seasoned my little treasures. With my fork, I cut the firm potato pillow in half, exposing the fine filling placed there by ancient hands, refined through generations of argument, fulfilled by sunlight, pitchforks, and cauldrons of boiling water. I flipped its gaping side down in a pool of butter and smeared it across the plate.

The first bite made me close my eyes. The multipurpose room fell silent and every cavity in my head absorbed a humble gift composed of elements that sang secret lyrics to notes along an archetypal scale, a harmony to my subconscious. In my pirohi rapture I could be lost and found, week after week, even when I reached the age when ardent kisses tried to surpass it, and never really could.

Excerpt from Rust Belt Boy, Stories of an American Childhood by Paul Hertneky. © 2016 Paul Hertneky. Published by Bauhan Publishing, Peterborough, New Hampshire. Used by permission.