Dimitri Keriotis on Dangling the Literary Carrot

Dimitri Keriotis’s short story collection The Quiet Time is forthcoming this fall from Stephen F. Austin State University Press. His stories have appeared or are forthcoming in the Beloit Fiction Journal, Flyway, BorderSenses, Evening Street Review, and other literary journals. He teaches English at Modesto Junior College and co-coordinates the High Sierra Institute. He and his family live in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada.

At the end of last semester, memoirist and poet Suzanne Roberts came to Modesto Junior College (MJC) to read and to talk with students. A couple of nights after the event, I walked into an English 101 class and instantly heard, “That was really something Thursday night.” Tito, a re-entry student in his fifties, was talking to me. He repeated, “That was really something.”

“Yeah? What specifically?” I asked.

“Just going and hearing an author, a real author. That’s something I’ve never done before. I didn’t know what to expect, but, man, was that really something. I can’t wait to read her book.”

I teach in a community where literary events are as rare as double rainbows. Not surprisingly, most of my students have not heard of a book reading, which makes attending one out of the question. Even those who have heard of readings rarely want to go to one. P&W funding has allowed our school to consistently bring writers to MJC for the past eight years. Comments like Tito’s are not unusual. But to be honest, most students who attend our readings do so because the event is part of a class, or because it is offered as extra credit. It is unfortunate that just like many of my colleagues, I resort to such a tactic to ensure a decent turnout—attach an extra credit assignment to the reading. This move feels like a foul, as if I’m paying my students to become part of a large enough audience. It saddens me to think that without this approach only five students would probably show up. But is dangling a carrot wrong if it helps students grow? Tito’s comments suggest not. Those of us who savor literary events feel personal growth happening as we listen to a writer deliver a gripping passage, answer a juicy question, or discuss issues of craft, so we return time and time again, but how can those unaware know to go? They can’t unless guided there by way of an incentive.

More often than not, my students later report that a reading was worth their time. After the Suzanne Roberts reading, a student e-mailed me about it: “As I headed to the Little Theatre, I really wanted to be at home on my couch playing the latest version of Grand Theft Auto [this is verbatim!], but I needed the extra credit, so I went. I thought the whole thing was going to be stupid, but I’m glad I went. She was cool, and I learned something new. I might even go to another one someday.”

Enough of my students have been turned on to literature by hearing authors read their work, answer their questions, and talk with them one-on-one while their books get signed that I won’t dare ditch my approach. We don’t always know what’s good for us until someone basically forces us to do something that can have a lasting effect.

Anyone for some extra credit?

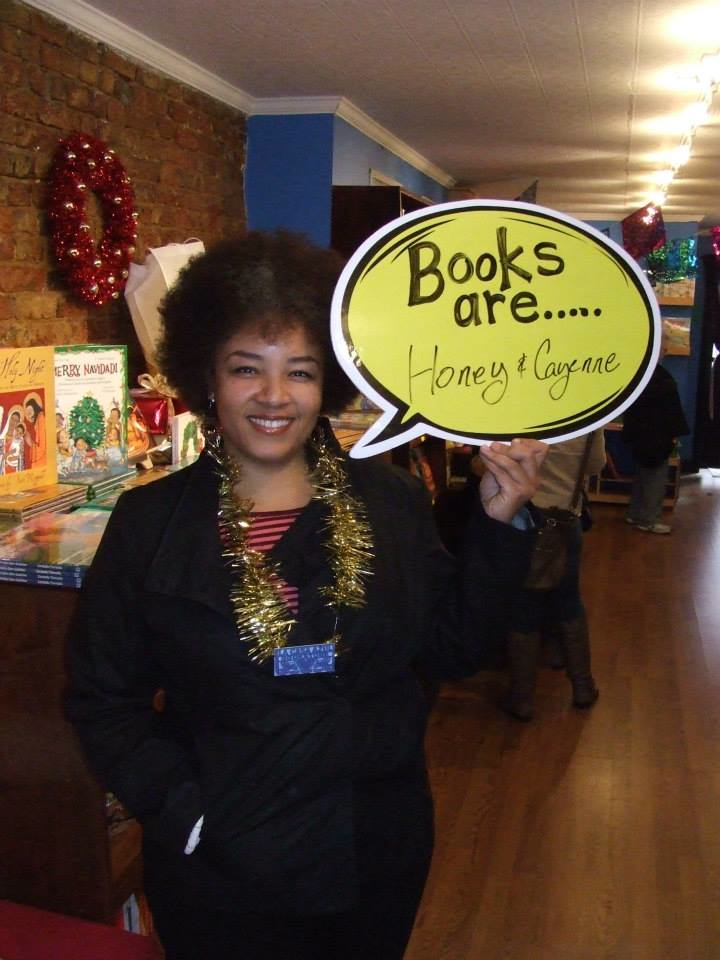

Photo: Dimitri Keriotis. Credit: Ingrid Keriotis.

Major support for Readings/Workshops in California is provided by The James Irvine Foundation. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

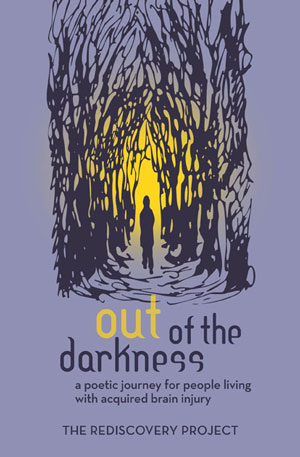

In my years of working with people who’ve experienced an acquired brain injury (ABI), I often hear how destabilizing and isolating the cognitive, emotional, social, and physical aftermath of ABI can be.

In my years of working with people who’ve experienced an acquired brain injury (ABI), I often hear how destabilizing and isolating the cognitive, emotional, social, and physical aftermath of ABI can be. The project was conceived of in 2011 during a discussion I had with poetry therapist John Fox, CPT. Years earlier, during grad school, I attended John’s poetry therapy class and felt an affinity for his work with poetry as healer. By 2012, John’s organization, Institute of Poetic Medicine, was on board to graciously fund the program. Rediscovery Project was launched later that year at Brain Injury Network of the Bay Area and continued in 2013, thanks to funding from Institute of Poetic Medicine, P&W’s Readings/Workshops program, and Bread for the Journey-Marin Chapter.

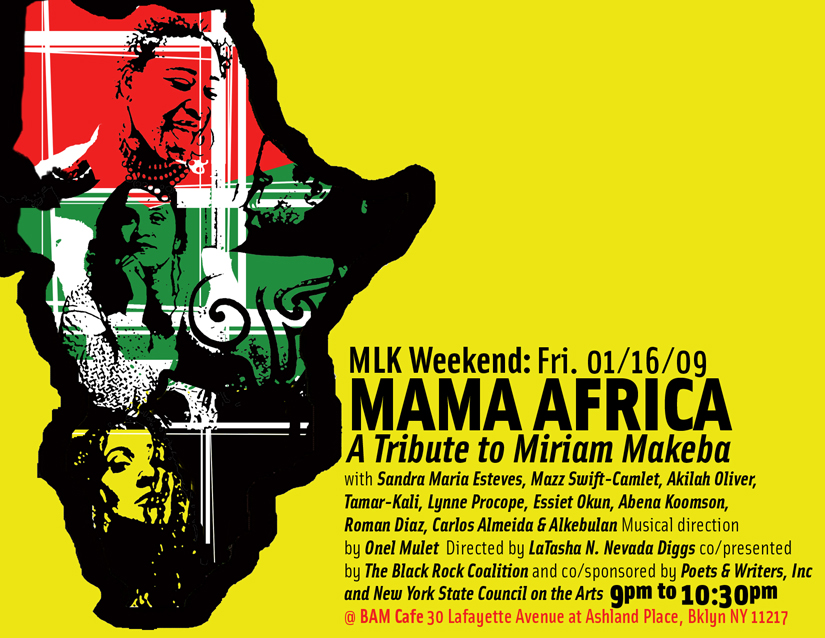

The project was conceived of in 2011 during a discussion I had with poetry therapist John Fox, CPT. Years earlier, during grad school, I attended John’s poetry therapy class and felt an affinity for his work with poetry as healer. By 2012, John’s organization, Institute of Poetic Medicine, was on board to graciously fund the program. Rediscovery Project was launched later that year at Brain Injury Network of the Bay Area and continued in 2013, thanks to funding from Institute of Poetic Medicine, P&W’s Readings/Workshops program, and Bread for the Journey-Marin Chapter. Somewhere in the Bronx there is a community garden called Hispanos Unidos. There, a cherry tree produces thirty pounds of cherries annually. Cucumber, cabbage, beans, figs, jalapeño peppers, peaches, and eggplants are grown and harvested. Tinkerbelle the cat guards the flock of chickens that live underneath the makeshift house. Inside the house on a wall is the worksheet for those who maintain the garden. The membership is ten dollars per month for men, five for women. The house serves as site of inquiry and celebration and as a location where Latinos maintain their cultural ties and language. It is a place where one can disregard the actual city residing outside the gates of the garden, where one can find respite in an array of fruits and vegetables. Where a rooster crows above the overhead subway train. It is gardens like this one that became the inspiration for Lincoln Center’s La Casita poetry and music festival.

Somewhere in the Bronx there is a community garden called Hispanos Unidos. There, a cherry tree produces thirty pounds of cherries annually. Cucumber, cabbage, beans, figs, jalapeño peppers, peaches, and eggplants are grown and harvested. Tinkerbelle the cat guards the flock of chickens that live underneath the makeshift house. Inside the house on a wall is the worksheet for those who maintain the garden. The membership is ten dollars per month for men, five for women. The house serves as site of inquiry and celebration and as a location where Latinos maintain their cultural ties and language. It is a place where one can disregard the actual city residing outside the gates of the garden, where one can find respite in an array of fruits and vegetables. Where a rooster crows above the overhead subway train. It is gardens like this one that became the inspiration for Lincoln Center’s La Casita poetry and music festival.

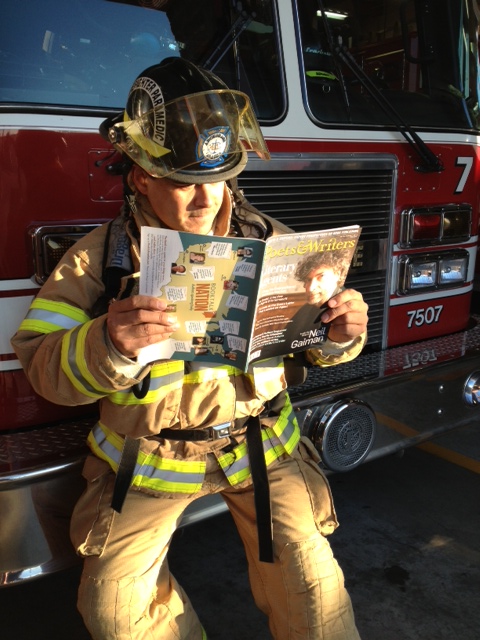

What are your reading dos and don’ts?

What are your reading dos and don’ts?

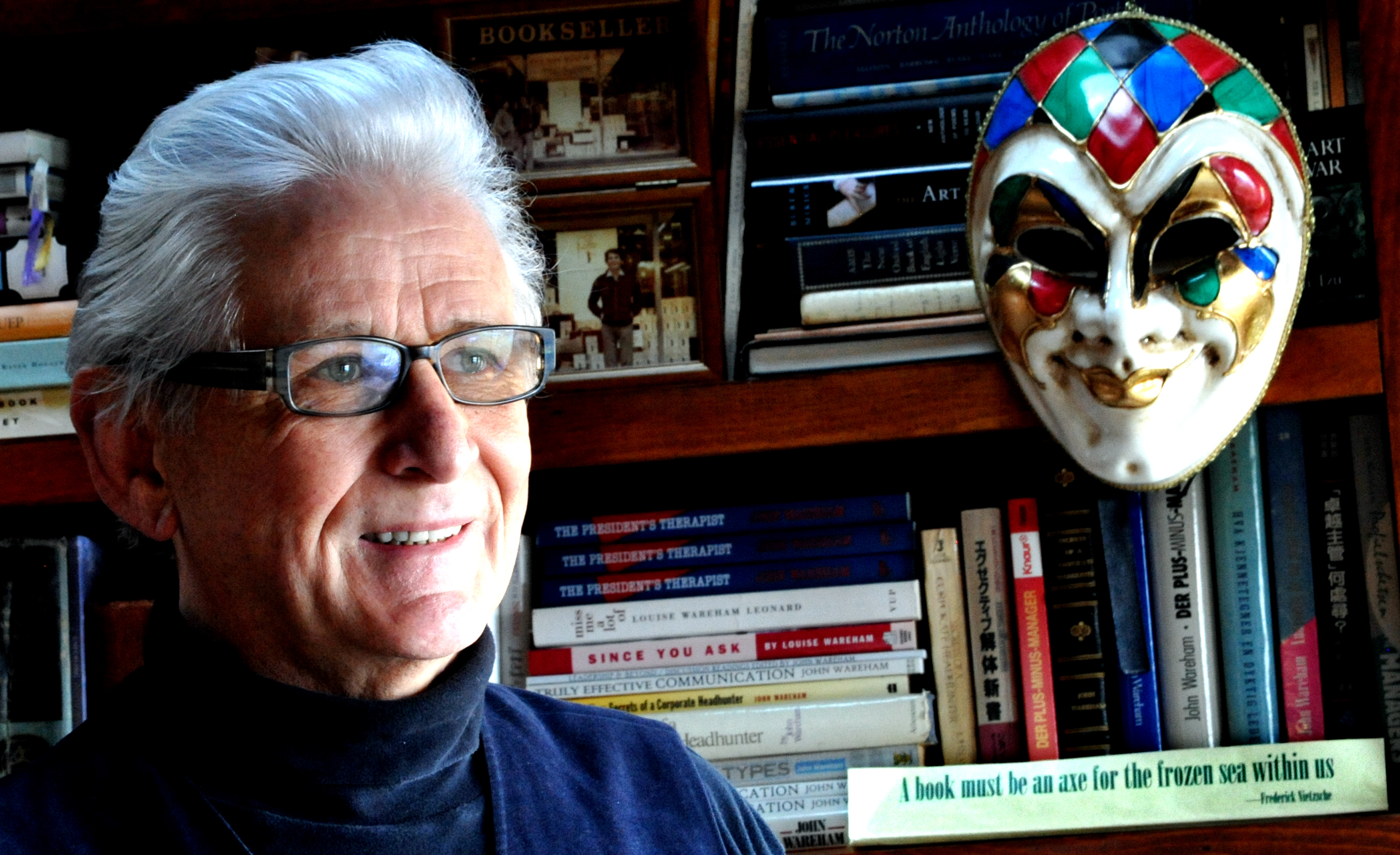

I have spent a lifetime advising corporations how to select and develop winning teams and leaders. One day nearly twenty years ago, an aspiring executive client with a drug habit wound up in Rikers Island, and gravitated to a rehab program.

I have spent a lifetime advising corporations how to select and develop winning teams and leaders. One day nearly twenty years ago, an aspiring executive client with a drug habit wound up in Rikers Island, and gravitated to a rehab program.