Carolyn Kellogg is staff writer at the Los Angeles Times where she writes about books and literary culture and can often be found blogging at the Los Angeles Times Jacket Copy. Her work has recently appeared in the Columbia Journalism Review, Black Clock, Bookforum, the anthology The Devil's Punchbowl: A Cultural and Geographic Map of California Today (Red Hen Press, 2010), and on the Paris Review website.

![]()

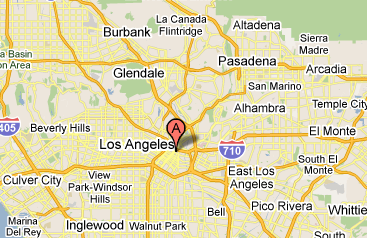

Like many people in Los Angeles, I came here from somewhere else—Rhode Island, by way of New Hampshire—and the city’s beauty, its hugeness, urbanness, and unknowableness made me stay. I still don’t know all of Los Angeles, because however well mapped, well photographed, and well chronicled, it’s a city that is also eminently up for reinvention. That’s a trope about those who come here too—that the West Coast in general, and Hollywood in particular, is a place for reinventing yourself—and if it’s a tired truth for people, it’s what draws them here. Raymond Chandler, Joan Didion, Nathanael West, John Fante, Charles Bukowski, Chester Himes, Ross Macdonald, Harlan Ellison, Ray Bradbury—even those typically associated with other regions of the country—William Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Aldous Huxley, all were informed by the city, some in ways that became evident in their work. Perhaps the writers who carry on that tradition today—Mona Simpson, Gary Phillips, Susan Straight, Marisa Silver, Rachel Kushner, Mark Danielewski, Salvador Plascencia, T. C. Boyle, Michael Jaime-Becerra, Aimee Bender, Carolyn See, Jane Smiley, Percival Everett, Alex Espinoza, and Sarah Shun-lien Bynum, among others—are also drawn to this city’s constant revision, its moving parts intersecting in unexpected ways.

While my job is to write about books and literary culture for the Los Angeles Times, I often find new venues and attractions along the way. I don’t think I will ever know all of this vast metropolis or the endless riches it has to offer.

Literary Locations

Literary Locations

El Alisal (200 East Avenue 43), named for the sycamores that surround it, is the home built by Charles Fletcher Lummis, who in 1884 walked from Ohio to California to take a job as the Los Angeles Times’ first city editor. His letters to the paper chronicling his 143-day walk are collected in A Tramp Across the Continent, his first book, published in 1892. He eventually became the editor of the magazine Out West, publishing writers such as John Muir and Jack London. In 1905 he became city librarian and in 1907 established the Southwest Museum, known for its collection of Native American artifacts, many of which Lummis himself gathered. It took Lummis twelve years to build his stone and wood home, which he did with his own hands. While it now sits in a nook near the Arroyo Seco Parkway, it was once a grand place that attracted the city’s cultural luminaries for galas—which Lummis called “noises”—that went well into the night.

The Los Angeles Public Library (630 West Fifth Street) has seventy-three branches, of which the central library is the heart and historic jewel. The building, capped by a glittering mosaic pyramid and a “torch of knowledge,” was completed in 1926; it includes an oft-overlooked, mural-filled atrium on the second floor. In 1986 a devastating fire destroyed more than four hundred thousand of the library’s books, but it galvanized the city to improve and restore the overcrowded building. The resulting expansion included room for computers on every floor and a contemporary auditorium where the library holds its ALOUD series—lectures, performances, and discussions with writers such as T. C. Boyle, Michael Chabon, Christopher Hitchens, Arianna Huffington, and Colson Whitehead. Between Flower Street and the library’s front door sits a small park, threaded with walkways, a long fountain, and, of course, benches, convenient for reading.

“Los Angeles, give me some of you! Los Angeles come to me the way I came to you, my feet over your streets, you pretty town I loved you so much, you sad flower in the sand, you pretty town.” That’s Arturo Bandini, the alter ego of John Fante, in the 1939 novel Ask the Dust. Bandini and Fante’s stomping grounds were Bunker Hill, a ridge along the west edge of downtown Los Angeles that at the time featured rows of Victorians that had been chopped up into seedy boarding houses. The neighborhood was targeted for redevelopment in 1955 and much of the hill itself was razed. Some elements remain, though, including the funicular Angel’s Flight, the shortest railway in the world. Restored in the early nineties, Angel’s Flight runs between Hill Street and California Plaza and costs twenty-five cents to ride—almost affordable enough for Arturo Bandini.

When Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World, moved from England to Southern California in 1937, in his early forties, he did what might be expected of a middle-aged Brit formally educated at Eton and Oxford: He worked on screenplays. But Huxley was restless and curious and eventually dabbled in psychedelics while living in the far desert town of Llano near Palmdale, and in a nearby mountain settlement called Wrightwood, where behind his cabin, in a trailer out back, he wrote Ape and Essence. Back in Los Angeles, Huxley had become friends with Jiddu Krishnamurti and became deeply involved in a branch of Hinduism called Vedanta. He and friend Christopher Isherwood frequented the Vedanta Temple (1946 Vedanta Place) in Hollywood, which is open to the public.

If you want to see the Gutenberg Bible, Jack London’s drafts of The Call of the Wild, Christopher Isherwood’s personal photos, and the Ellesmere Manuscript (ca. 1410) of the Canterbury Tales, spend an afternoon at the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens (1151 Oxford Road). Industrialist Henry Huntington’s rare books collection forms the basis of this library, and a cultivation of fourteen thousand rare and exotic plants make up more than a hundred acres of the botanical gardens—perfect scenery for drafting a poem or story. His former estate houses the library, its permanent exhibits, and artwork handpicked by his wife. In recent years, the library, which has a staid reputation, has made some surprising acquisitions, including science fiction writer Octavia Butler’s papers, and those of Charles Bukowski.

The eight tutoring centers that make up 826 National, Dave Eggers’s literacy nonprofit, include street-front retail stores with unusual themes—the Brooklyn Superhero Supply Company in New York City; the Greenwood Space Travel Supply Company in Seattle; Liberty Street Robot Supply and Repair in Ann Arbor, Michigan; the Boring Store in Chicago; and the Pirate Store in San Francisco. In Los Angeles, it’s the Echo Park Time Travel Mart (1714 West Sunset Boulevard), a quickie-mart for the time traveler who’s passing through. Proceeds from its sales—merchandise includes beer cozies, ray guns, mustaches for every era—support the nonprofit.

Author Dwellings and Haunts

While the ordinary tourist might be enticed by tours of movie star homes, writers may get more out of the houses and hangouts of legendary authors who lived and wrote in Los Angeles. Note that these homes aren’t the museum type—they’re currently occupied and considered private.

The Great Gatsby is now considered one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, but F. Scott Fitzgerald’s fame was far from secured a decade after its publication. In the late thirties, with Zelda in and out of institutions and their daughter away in private school, Fitzgerald moved to Hollywood, ready to make money in pictures. For a time, he brought in a good salary from MGM, but like his earlier earnings, it went fast, and then the work dried up. In the summer of 1940 his twice-yearly royalty statement for Gatsby and Tender Is the Night totaled a whopping $13.13. In November of that year, he had a mild heart attack in Schwab’s Pharmacy (which closed in 1983 and was knocked down in 1988 to make way for a succession of malls) and was advised to rest, so he moved out of his third-floor apartment and in with his lady friend, Sheilah Graham, at 1443 North Hayworth Avenue in West Hollywood, where he died at the age of forty-four from a second heart attack.

Nathanael West’s family money was pretty much gone by the early 1930s when he moved to Hollywood. He’d already clocked time as a hotel clerk back in New York City as he wrote novels and screenwriting paid only slightly better. He was living in the Parva-Sed-Apta Apartments (1817 Ivar Avenue)—the type of place that has only a Murphy Bed and a kitchenette—when he wrote The Day of the Locust. He sent his friend F. Scott Fitzgerald the galleys, noting that it wasn’t easy writing a book between “working on westerns and cops and robbers.” Although The Day of the Locust wasn’t an immediate hit—it sold fewer than fifteen hundred copies—it has now come to be seen as one of the most bleakly incisive stories of strivers in Hollywood.

When Thomas Mann won the Nobel Prize for Literature, he was every inch a German writer. But that was 1929, and after Hitler’s rise, he left the country. Mann lived in Switzerland and taught at Princeton before moving to Los Angeles. He settled in Pacific Palisades, a small community high in the hills above the coast, living first in a rental (740 Amalfi Drive) and then in a house (1550 San Remo Drive) he and his wife built. Although he became a U.S. citizen in 1944, Mann continued to write in his native German. Doctor Faustus, first published in 1947 in German, when Mann was seventy-two, was published in English a year later by Alfred A. Knopf. In 1952 Mann moved back to Switzerland, where he died in 1955.

Charles Bukowski’s tales of living an underground life are full of dives and dames and occasional depravities. The logical stop to honor the poet and novelist might be the Terminal Annex of the U.S. Post Office (900 North Alameda Street), where he worked, memorialized in his semiautobiographical book Post Office. But, Bukowski, who Time magazine called a “Laureate of American Lowlife,” likely enjoyed himself far more at the race track at Santa Anita Park (285 West Huntington Drive), located east of downtown in Arcadia, where he spent hours betting on horses. (His widow hopes to turn their San Pedro home into a museum, but for now, she still lives there.)

Bookstores

Los Angeles is home to dozens of independent bookstores, but the three most tuned in to contemporary literary culture are Vroman’s Bookstore in Pasadena, Book Soup on the Sunset Strip in West Hollywood, and Skylight Books in the Los Feliz neighborhood. Vroman’s (695 East Colorado Boulevard) claims to be California’s oldest and largest independent bookstore. While its Pasadena location seems out of the way to some, it regularly hosts big draws like David Sedaris. Book Soup (8818 Sunset Boulevard), which offers a heavy selection of art titles and hip fiction in a compressed space, has got to be one of the most awkward places on record to give a reading. Still, its L-shaped layout, thinner than a grocery store aisle, does offer intimacy and attracts big-name authors such as Patti Smith. Skylight Books (1818 North Vermont Avenue)—known to locals for the enormous ficus tree that grows in the middle of the store, just under the eponymous skylight—hosts readings by authors such as David Mitchell and Dave Eggers and features an eclectic stock (you’ll find Chomsky with your Chabon) and a newly opened annex with art books, comics, and magazines.

Two of the most unique comic bookstores in the country are located in Los Angeles: Secret Headquarters, named one of the world’s ten best bookshops by the Guardian in 2008, and Family Bookstore. Secret Headquarters (3817 West Sunset Boulevard) is designed like a men’s club from the 1930s, accented in dark wood with a pair of elegant leather chairs by the front window. Split equally between mainstream superhero comics and indies, the stocked titles cater to adults who fell for comics when they were younger. Family Bookstore (436 North Fairfax Avenue), co-owned by indie comic artist Sammy Harkham, is a highly curated bookstore focused on comics and art. Family irregularly hosts an array of events from author readings to gallery shows to talks, featuring the likes of Trinie Dalton, author of Wide Eyed (Akashic Books, 2005); graphic novelist Jaime Hernandez; and Michel Gondry, director of Eternal Sunshine for the Spotless Mind.

Other notable bookstores: Diesel (225 Twenty-Sixth Street at the Brentwood Country Mart) in nearby Brentwood is known for its author events and “urban California aesthetic.” Eso Won Books (4331 Degnan Boulevard) in the Leimert Park neighborhood, immediately recognizable by the silhouettes of James Baldwin and Malcolm X in its front window, caters to the city’s African American community. Iliad Bookshop (5400 Cahuenga Boulevard) in North Hollywood was named one of the best used-book stores in L.A. by Los Angeles magazine. Libros Schmibros Lending Library & Used Bookshop (2000 East First Street)—part library, part used-book store—is a nonprofit organization founded by former National Endowment for the Arts reading initiatives director David Kipen; Mystery and Imagination Bookshop (238 North Brand Boulevard), which sells used and out-of-print sci-fi and mystery books, is known for being Ray Bradbury’s favorite bookstore and it’s where he celebrated his ninetieth birthday; Stories (1716 Sunset Boulevard) features a mix of new and used books and a café with a gritty but dressed-up patio where authors read.

Festivals and Reading Series

The annual Los Angeles Times Festival of Books takes place over a spring weekend and hosts more than one hundred fifty thousand people. Speakers include best-selling authors such as T. C. Boyle and Jonathan Lethem, as well as prominent agents and editors. There is a children’s area, which features stage performers—such as actress Bernadette Peters, who read her children's book while perched in an enormously oversized chair at the 2010 festival—and music, a poetry stage, and hundreds of tents with vendors selling books, journals, and other bookish wares.

In addition to traditional venues like bookstores, readings can be found in unusual places as well, if you know where to look. Every other month, Vermin on the Mount, which features readers from the indie scene, is held at the dimly lit Mountain Bar (473 Gin Ling Way) in Chinatown, which is partially owned and decorated by artist Jorge Pardo, a MacArthur "Genius" Fellow. Tavin (1543 Echo Park Avenue), a boutique and salon located in Echo Park, holds semiregular readings with female authors. Over in Culver City the Taylor de Cordoba (2660 South La Cienega Boulevard), a contemporary art gallery, regularly brings together authors and culinary types as part of its Eating Our Words series. Recent pairings included poet Dana Goodyear and chocolate maker Patricia Tsai. Rhapsodomancy, a series that features two poets and two fiction or nonfiction authors—past participants include Sarah Manguso, Chris Abani, and Jericho Brown—holds its readings at the dark, red-walled Good Luck Bar (1514 Hillhurst Avenue) in Los Feliz. And Tongue and Groove, a monthly offering of short fiction, personal essays, poetry, and spoken word, accompanied by music, is held at the Hotel Café (1623 1/2 North Cahuenga Boulevard) in Hollywood, with raw brick walls and fewer seats than attendees.

Some major literary series in Los Angeles do not have permanent homes: Writers Bloc, which typically holds its programs in venues in Beverly Hills, has featured conversations with high-profile writers such as Paul Auster, Joan Didion, Norman Mailer, Joyce Carol Oates, Salman Rushdie, and David Foster Wallace, plus stunning duos with artists such as Christopher Hitchens and Kurt Vonnegut, Dick Cavett, and Mel Brooks. Launched in 2010 Live Talks Los Angeles has hosted authors such as Scott Turow and Robert Reich, who discussed their latest books in onstage interviews. On the edgier side, Rare Bird Lit, also launched in 2010, has hosted Chuck Palahniuk, James Ellroy, and Dennis Lehane. Events are often held at Largo at the Coronet (366 North La Cienega Boulevard), a 1920s variety theater.

A few more unexpected places you might find a literary event, if the timing is right: Beyond Baroque Foundation (681 Venice Boulevard), a legendary poetry center hosts readings by local and traveling poets and open-mike nights, and the Steve Allen Theater (4773 Hollywood Boulevard), where the Center for Inquiry–Los Angeles has hosted events with the Rumpus and McSweeney's Books.

Bars and Cafés

Established in 1919, there is still no better place in Hollywood to get a martini than Musso and Frank Grill (6667 Hollywood Boulevard), which perfected this traditional drink for no less than William Faulkner, Nathanael West, John O’Hara, Raymond Chandler, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Its stretch of Hollywood Boulevard now features tourist shops and the paparazzi-friendly Geisha House, but in the 1930s it was surrounded by bookstores: Pickwick on one side and Stanley Rose on the other. Writers who considered themselves slumming in Hollywood would come to Stanley Rose for the notable book selection, Rose’s erudite and colorful conversation, and the back room, where commiseration often turned swiftly to boozing. Musso and Frank had laid claim to a few back rooms on the block, and legend has it that the writers got full restaurant and bar service in the bookstore’s back room. In the 1950s Stanley Rose’s closed and Musso and Frank expanded into its former space. James M. Cain, Budd Schulberg, William Saroyan, and John Fante were among those who drank there—and, if you order a Musso and Frank martini at the bar, you will be too.

While these bars aren’t literary per se—famous writers didn’t drink or pen their famous works there, agents and editors don’t schmooze there—their bookish décor will, perhaps, inspire your work-in-progress: Hemingway’s (6356 Hollywood Boulevard), featuring ceiling high shelves of old books, a wall of vintage typewriters, and a smoking patio describe as “a bit Paris, a bit Key West, a bit Cuba” serves up specialty drinks named after the author. The law books lining the walls of Hyperion Aveue Tavern (1941 Hyperion Avenue) in the Silver Lake neighborhood do nothing to indicate that this used to be a boys-only leather bar, nor does the live music, which features bands that range from quiet country and folk to full-blown punk. Library Bar (630 West Sixth Street) is located downtown in the shadow of the central Library. While it’s too dark to read the books on the shelves, the décor, food, and drinks might just be enough to stir up a lively literary discussion. The Wellesborne (10929 West Pico Boulevard) in West L.A., with its booth seating, fireplace, and book-lined walls, is chock full of inspiration.

Los Angeles is big on personal space—large apartments, wide yards—but when it comes to finding a public space to write, it gets tricky. As in any other city, coffee shops can be a good bet, but be warned: Here in L.A. they’re brimming with screenwriters, who’ve set up with laptops and lattes. A favorite for locals is the Starbucks-alternative Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf, a spiffy Southern California chain that provides a Wi-Fi code on request. The random library branch is a personal favorite of mine, but you have to get a library card to log in to the Internet. For visitors? The best bet is the backyard of that person you’re staying with.

Writers who know Los Angeles best have done some of their best writing about freeways. Think Joan Didion in her novel Play It As It Lays or Raymond Chandler in The Little Sister. After midnight on a weeknight try driving on Interstate 405 and over the hill into the valley, or early on a Sunday morning take the 10 from downtown to the ocean or head north on the Pacific Coast Highway. The rhythm of Los Angeles’s roads has seeped into its decentralized heart, into the minds of writers for decades, and you, too, will hear it as your wheels spin and spin and spin.