Poetry contests sponsored by the International Library of Poetry and its affiliates—the International Society of Poets, Watermark Press, poetry.com, and so on—have drawn submissions from more than five million poets since 1983, when the organization was founded in Owings Mills, Maryland. Unlike most literary contests, those sponsored by the ILP charge no entry fees. Another distinctive characteristic of the ILP contests is the near certainty that every submission will win publication in one of the dozens of anthologies the organization publishes each year.

No entry fee? Little chance of rejection? Any poet worth her iamb has reason to be suspicious. And, indeed, the ILP appears on several Internet-based contest-scam watch lists. The Academy of American Poets, a venerable nonprofit organization, receives many complaints from ILP contestants who confuse the Academy (www.poets.org) with the International Library of Poetry (www.poetry.com). “We often get calls demanding to know when some anthology or plaque reproducing the caller’s poem will arrive—and of course, these products have always been paid for in advance,” says Tree Swenson, the Academy’s executive director. “It’s hard enough to maintain the distinction of our programs from those of other serious literary organizations; it’s a nightmare to be confused with commercial firms that seem unconcerned with literary quality.”

The Better Business Bureau of Greater Maryland has received hundreds of complaints in recent years about the ILP. While it notes that the complaints have been resolved and that the ILP has a “satisfactory record” with the bureau, the BBB does classify the ILP as a “vanity publisher” and makes note that the quality of poetry “does not appear to be a significant consideration for selection for publication.” The organization even drew the attention of 20/20, the ABC news program, which reported on an ILP contest in 1998 and concluded, “The real winner of the contest is the company, that’s clear.”

Clear profit, for sure, but then ILP is a for-profit business. It markets its anthologies, each one containing hundreds of 20-line or shorter poems, for $59.95 to the poets it publishes. This is another way that ILP contests differ from traditional literary contests: Published authors do not receive gratis copies, a standard protocol for traditional publishers. To see their names in print, the published poets must purchase the anthologies, which are titled A Blossom of Dreams, A Falling Star, A Fleeting Shadow, and so forth. On top of the $59.95 cost of an anthology, ILP poets can pay $25 to have autobiographical material accompany their work. Poets can also purchase merchandise featuring their own poetry: wallet cards, tote bags, and plaques. Watermark Press, an ILP affiliate, will publish an individual poet’s collection for a fee, ranging from $500 to $1,500. Membership in the ILP is an additional $125. Benefits of membership include a member plaque, a cloisonne pin, a decal, a patch, a subscription to the organization’s quarterly magazine, and a $100 discount on ILP conference registration fees, which are $600 a head (not including transportation, food, and lodging). The dollars do add up.

Most poets who are savvy in the ways of standard publishing practice steer clear of the ILP and businesses like it. They prefer contests that choose renowned poets to serve as judges, thus giving the contests—and the winners—genuine literary cachet. But lately some well-respected poets, including Pulitzer Prize winners, National Book Award finalists, a former chancellor of the Academy, a former U.S. poet laureate, and state poet laureates, have lent their time and talent—for a fee—to the organization. What gives? Is there more to the ILP than meets the jaundiced eye?

Poets still can enter any of several ILP competitions, including monthly contests that offer a $1,000 prize and an annual contest that offers $10,000, by completing an online entry form and submitting a poem of no more than 20 lines. Only poems that contain obscenities or are otherwise deemed offensive by the ILP’s editorial staff are rejected. All other submissions are automatically posted on poetry.com and accepted for publication in an anthology printed by Watermark. Many poets whose poems appear in an anthology are named semifinalists for “Poet of the Year” and invited to attend a biannual conference, where they contend for the $20,000 grand prize. According to the ILP, more than 4,000 poets from 60 countries attend its conferences each year. Typically the audience is composed of “very ordinary citizens who happen to write poetry,” says Len Roberts, ILP’s education director. “Very, very few MFAs…mostly people like your aunt or cousin who now and then pick up a book of rhyming poetry, love it, and then write a rhyming poem for a relative or for nature.” One of the biggest criticisms lodged against the ILP is that the organization takes advantage of poetry hobbyists by offering credentials no traditional publisher or editor would value.

Roberts, who is the author of 10 books of poetry, including Black Wings (Persea Books), which was selected by Sharon Olds for the National Poetry Series in 1988, does not dispute that the ILP had image problems when he joined the staff in 2000, but he says things are changing. “Four years ago, when poetry.com asked me to be their education director, they invited me to one of their conferences. It was awful,” says Roberts. “The presentations overlapped, and most of the topics touched on self-publishing. The ‘big names’ were singers, entertainers, etcetera.” Since then, Roberts has solicited distinguished poets to participate in ILP activities. He also signed up judges and presenters, and arranged for lectures that dealt with issues beyond self-publishing. Roberts says that the ILP’s audience is “truly mainstream America,” and that his goal is “to bridge the gap between what contemporary poets are doing and these folks.”

But is asking Pulitzer Prize–winning poet W.D. Snodgrass and former Academy chancellor David Wagoner to share the bill at the 2004 conference in Philadelphia with Florence “Mrs. Brady Bunch” Henderson and the Shirelles bridging the gap or accentuating it?

Grace Cavalieri, author of eleven books of poetry and longtime host and producer of the radio program The Poet and the Poem, has attended several ILP conferences, including the 2004 Philadelphia event, and thinks Roberts is helping the ILP undergo a metamorphosis. “He hired ten presenters, all with advanced degrees (me among them), and at the convention[s] we give seminars and lectures and real teaching sessions, with heartwarming results,” Cavalieri says. “It is poetry for the masses, as far as I am concerned, and my mission is altruistic.”

Michael Waters, a professor at Salisbury University in Maryland and the author of 11 books of poetry, had reservations when Roberts invited him to lecture on the creative process at a 2002 conference in Hollywood, California. “I didn’t know much about the organization except its not-so-great reputation,” Waters says. Roberts told Waters he was trying to change that reputation, and that big-name poets, including Snodgrass and former U.S. poet laureate Robert Pinsky, would be attending. Roberts suggested that Waters speak with poets who had previously attended an ILP conference, so he called Fleda Brown, Delaware’s poet laureate, and Thom Ward, the editor of BOA Editions. “I asked them what went on,” Waters says. “What they told me is that I should do exactly what I would do at other conferences, but that these people would be at a high school level.”

Waters says that he was allowed to be honest with ILP participants; he was free to tell them that they should not have to pay to have their poetry published. “I think if [a publisher] accepts work, [it] should give one free copy. What [the ILP is] doing is something different from what we normally see. They’re packing in hundreds and hundreds of short poems in the anthology, and I imagine it’s a moneymaking enterprise for them. What they then do is give these folks the chance not only to buy it, but also to win a large chunk of money. I don’t like the idea. It’s nothing that I would do myself. On the other hand, it’s somewhat comparable to what other folks do when they send in twenty-five dollars to have their own manuscripts read.”

Divergent opinions about the ILP persist. Some say that opportunities to educate the general public about contemporary poetry should be embraced. Others cringe at the idea of revered poets associating with an organization that doesn’t use merit as a basis for publication. Still others take a practical stance: Poets, too, have to make a living, and the reported stipends that the ILP pays to participating poets are sizable, ranging from $5,000 to $10,000.

“There are people for whom, in many ways, the ILP works,” says Lee Briccetti, executive director of Poets House, a nonprofit literary center and poetry library in New York City. “These people are interested in seeing themselves in print and being a link to their grandchildren or families. Their effort is more to get their words out to a community than to make a literary career.

“The real problem occurs,” Briccetti says, “when people don’t have information about how our field operates. We see a lot of people who are very pumped up and excited about what they have won without really understanding that it’s not a contest with literary clout. That is how poetry.com has built its business.” Briccetti believes that many people don’t understand that a lot of the trappings—plaques and pins and patches—are gimmicks, and that the organization takes advantage of their ignorance of how standard poetry publishers operate. “People are disappointed when they find out,” she says.

One of those disappointed poets was Nick Carbo. In the early 1980s, Carbo, who has subsequently published three full-length poetry collections with independent presses, submitted one of his poems to what was then called the National Library of Poetry anthology. It was accepted, and Carbo paid $45 for the anthology in which his poem appeared. “As a beginning poet, I had no idea what to expect,” Carbo says. “I fell for the biggest neon sign out there.”

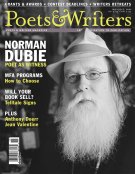

Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Stephen Dunn attended an ILP conference in Washington, D.C. in 2002. He says it was “one of the most humiliating experiences of [this] poet’s life.” Like Waters, Dunn was invited by Roberts, who told Dunn that he intended to improve the organization, and he offered Dunn an honorarium. After he accepted the money, Dunn says, he realized he had made a mistake and broke off further ties to the organization. But it was too late to back out of the event in D.C.

At the conference Dunn mingled with a large number of poets, many of whom proudly showed off their poetry trophies. Dunn says that, when he gave his reading, he felt that people were not listening; many seemed to be combing their hair and preening. He realized that they were preparing to be chosen for the $20,000 “Poet of the Year” prize. Dunn thinks “a good many poor people are duped” into believing their semi-finalist status validates their talent and, as a result, they think they have a good chance of winning big money. The problem is, everyone at the conference is a semi-finalist. “The organization covers itself by actually giving a few large cash awards on the last day,” he says. Dunn continued with his reading, but when actress Joan Collins suddenly arrived, Dunn says he was edged off the stage early so that she wouldn’t have to wait to make a grand entrance.

“When he read, the audience did not connect, for whatever reason, with his poems,” Roberts says. “Being who they are, they began to talk—there were about twenty-five hundred people at the banquet reading—and then we could hardly hear Stephen at all. He finished the reading, told the audience that they were probably the most offensive audience he had ever read to, and that was that.”

“On the other hand,” Roberts says, “Lucille Clifton read at the next conference and received two standing ovations at both of her readings. She connected, the audience responded, and there was a bit of that poetry magic in the air.”

Recently the New York State Consumer Protection Board, a state-funded watchdog organization, commenced an investigation into poetry.com and the ILP. Although Jon Sorensen, director of marketing and public relations for the NYSCPB, believes that the ILP “takes advantage of people both emotionally and financially,” he was forced to postpone his investigation because of the low volume of complaints about the organization.

Margo Stever is a poet, founder of the Hudson Valley Writers’ Center, and coeditor of Slapering Hol Press.