Since the financial crisis of 2007–2008 and the recession that followed, the book business has shuddered through intense turbulence: corporate mergers, acquisitions, spinoffs, and bankruptcies; startups that sizzled and then ceased; the fall of Borders and the rise of Amazon; new book formats, business models, imprints, and agencies; litigation; technological upheaval; and a host of other unexpected challenges and radical transformations.

And yet writers keep writing and readers keep reading. In the midst of such tumult, that’s just about all the stability I could ask for—and perhaps all our business really needs.

But what of the publishing professionals who came of age in the business during those disruptive years? Could it be that the agents and editors who took root in this new climate are of a hardier stock, and that their perspectives on culture and commerce will differ significantly from the generations that preceded them? As this group of up-and-comers becomes the establishment, they will shape what gets published, why, and how.

I recently invited four young agents—Claudia Ballard, Seth Fishman, Melissa Flashman, and Alia Hanna Habib—to my office to talk about what it means to be a literary representative today. Each of them has achieved success in the postcrisis years. Over a couple of six-packs of beer and some chips and cookies (blame the new economy for my chintzy spread) our conversation took off. Here are brief biographies of the participants:

Seth Fishman started his career in publishing at Sterling Lord Literistic in 2005, and has been an agent at the Gernert Company since 2010. His authors include Kate Beaton, Anna Bond, Ann Leckie, Randall Munroe, and Téa Obreht.

Claudia Ballard is an agent at William Morris Endeavor, where she has worked for nine years. Her clients include Marie-Helene Bertino, Marjorie Celona, Amelia Gray, Eddie Joyce, and Emma Straub.

Alia Hanna Habib became an agent at what is now McCormick Literary in 2010, after working for five years as a publicist at Houghton Mifflin. Her clients include John Donvan, Ophira Eisenberg, Elizabeth Green, Josh Levin, and Caren Zucker.

Melissa Flashman became an agent at Trident Media Group in 2002, after working as a “coolhunter” and an assistant at ICM. Her clients include Stephanie Mannatt Danler, Kristin Dombek, Stanley Fish, Emily Gould, and Kate Zambreno.

![]()

Let’s start with your first interaction with a writer. How does their material find its way to you, and when it does, what makes you respond to it?

Fishman: I was all about the small magazines when I first started out. My first client came from reading Tin House. People ask now whether those magazines matter; they do. Even if we don’t have time to read them now to look for new clients, our assistants are reading them—at least I hope they are. That first client led me to a number of other clients, including Téa Obreht and her book The Tiger’s Wife, which was my first sale. Those connections are incredibly important.

Habib: Whether I’m reading the Atlantic or a literary journal, if something grabs me the way it would grab anyone as a reader, I’m going to write to that person. Don’t we all look for clients that way? But I do a lot of nonfiction, and in many ways that process is different.

Aren’t there also many similarities: story and voice and that elemental thing that makes someone pay attention? What’s universal about how you respond as a reader and an agent?

Habib: I’ll give you an example. I was reading an article in the Atlantic about the first diagnosed case of autism by two writers, John Donvan and Caren Zucker, at a moment when I thought I had read more than enough about autism. The first line caught my eye. The reader in me noticed that I was reading the article really quickly. Then the literary agent part of me asked, “How do I help make this a book a lot of people will want to read?” I think our job is partly to see what the writer doesn’t see.

Ballard: There’s also a real community of writers out there, and incredible resources for unpublished writers to connect to the publishing community so that agents can find them. Tin House is a fantastic magazine for that, because they publish new voices every issue. It isn’t easy for writers who are just starting out, but writers refer other writers. The more you are tapped into a community, the more you’ll benefit from that flow. It’s about getting your feet on the ground and getting your name out in the universe.

Flashman: Two questions always come up when I’m at writers conferences. People in MFA programs always ask if they need to be in San Francisco or New York City, and people in New York always ask if they need to have an MFA. I don’t think either one matters, necessarily. What matters is that they are both cultural ecosystems. Maybe you don’t have an MFA and you live in Austin or Louisville. What matters is being around other writers, supporting one another’s work, and reading. Maybe you start a literary magazine, or maybe someone gets into the Oxford American, and through that door, three more writers come in. That’s how it works.

What about social media?

Habib: Social media can create those communities too. Roxane Gay did that so brilliantly—she created a ready readership for her books by engaging so openly and honestly on Twitter. She’s not my writer—I wish she were! But that’s another way to open the door.

Fishman: I’ve learned that different social media systems are for totally different things. For me, Twitter is for professional contacts, and Facebook is personal. I’m an agent but I also write, and when I put something on Facebook about my book publication day, I get three hundred likes—it’s like a super birthday. But if I put it on Twitter, I might get six retweets and fifteen likes.

Ballard: I don’t tweet, but I use Twitter to see what everyone else is talking about.

Flashman: I make secret lists on Twitter for different ecosystems. For instance, I’ve been thinking about a type of fiction you might call an art-school novel, and where to find the girls who like reading it. I know where they are on social media, and I know there are certain publishers and editors who can publish that type of book well. And I keep track.

So, social media is a way of being part of a community, rather than what publishers might call “platform”—thousands and thousands of followers who are primed to click Buy?

Ballard: Being tapped in doesn’t necessarily translate to platform. It’s a way in which you can engage. It makes it a lot easier for people who don’t live in places where a lot of writers happen to congregate. Still, when a writer sends me a query, I connect first and foremost with the writing.

What’s important for you to see in a query from a writer?

Fishman: All I want from a query letter is reasons to go to the next page—reasons to read the book. While I’d like to say I read everything, I have an assistant and we have interns who look at things first. When I look at a query letter, I read the first and third paragraphs. I don’t care about the synopsis—not because I don’t care what the book is about, but because a lot of writers don’t know how to write a good synopsis. The first paragraph is where writers will tell you about any direct connections to you.

Flashman: It will also tell you if this book is even in a category that you represent. I wouldn’t know a good science fiction novel if it punched me in the face. So if someone is pitching me science fiction, either there’s a connection or they liked one of my other novels, in which case I might be interested. But if there’s no connection to any of the authors I’ve represented, I’m just not the right agent. There is a great agent at my agency, John Silbersack, who does science fiction. He represents the Dune estate. He’s edited Philip K. Dick. He is the man. Those writers should be e-mailing him, not me.

How much material comes in to you in comparison to what you take on?

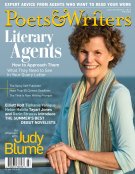

Ballard: Well, if your name is listed on the Poets & Writers website, you will get a lot of queries. I probably get a query every ten minutes. I have to engage with them very, very, very quickly. It’s important to make your query succinct and to target the right agent for you.

Fishman: Otherwise it’ll just get put away. My assistant filters things for me. Now I probably get only three or four every other week that the assistant thinks are good enough. I’m not looking for much more to represent right now. But the last book that my assistant brought to me and said, “You have to read this now,” I stopped what I was doing, read it, loved it, and sold it.

Ballard: I personally read all my queries, but it’s hard. It’s a volume game. But when you have a lot of volume, you pick out the things that you feel most connected with even more quickly. I do take referrals more seriously. It’s a two-way street. You want to feel a connection to the work, but you also want a writer to feel connected to you.

Do writers need to write better query letters to get your attention, or do they just need to write better books?

Flashman: They need to approach the right agents. I think there’s a way of focusing queries to ten or fifteen agents: Sit down with a legal pad, or your iPad, and find roughly ten novels that are similar. Writers usually thank their agent at the back of the book. Keep a running list of novelist, novel, agency, agent. Go to the Internet, make sure the agent’s still alive and taking on clients, and go from there.

Habib: I’d add, when you’re looking at those books that you love, to also look at lists of successful debuts and see who represented them. I think we’re all saying that when you get a query, and it’s from someone who’s read and liked one of your client’s books, it helps.

Fishman: There are so many other simple things. Make sure the person is the correct gender!

Flashman: “Dear Mr. Flashman…” no.

Fishman: And sure, we’re overwhelmed, but we want to find something good. We want that desperately. We’re not being assholes. We’re just being human. We connect with the things that we connect with. We have bad days; we have good days. If someone goes online and says, “Don’t submit something to me today,” on Twitter, then you shouldn’t, because that person’s really trying to tell you something.

Let’s talk about MFAs. Seth, you have a master’s in writing, and Melissa, you wrote a great essay about them in the anthology MFA vs NYC.

Flashman: I think some people might think I’m on Team NYC, and against MFAs, because I’m here in New York publishing. But I’m actually very pro-MFA, because I think some of those programs are like the WPA for writers—the good state programs especially, where they give writers money to go study. You don’t need to go when you’re twenty-two. It’s often better to go when you’re thirty, thirty-five, when you have more of a life behind you. But you don’t need to go to an MFA program at all. You can hang out with other writers and write anywhere.

Ballard: My take is that MFA programs attract like-minded writers. People who want to be a part of the writing community, or want to take the time to say, “I’m going to focus on this.” It doesn’t create talent, but it can provide you a lot of feedback and time. Some people feel the workshop scenario is not for them, but I find that people who are serious about a writing career tend to seek them out. It’s not a necessity. But it signals seriousness to an agent. Seth, you went to one—what do you think?

Fishman: I don’t necessarily perk up based on where a writer went. We’ve all seen work from writers who went to the famous places and we’ve passed on it. There are other hybrid programs that I would like to recommend, though. In the speculative-fiction world, the best thing I’ve seen is called Clarion. It’s five thousand dollars for six weeks, and features huge teachers like Neil Gaiman and George R. R. Martin. I represent a lot of people from there. It’s like a boot camp.

Flashman: So you’ve found that ecosystem.

Fishman: Right, I’ve found the ecosystem that’s perfect for me. And I love it and I shouldn’t be telling anyone about it. At the same time, I’m sure there are versions of it in other genres. There have to be.

Ballard: There are also writers conferences like Bread Loaf or Sewanee where writers seek out like-minded people who can’t take much time away from making a living, but are often incredibly talented.

Habib: And to get back to query letters: At least in our office, our assistants and interns do give a closer read of the material in the slush pile that says the writer got an MFA.

Fishman: I’m looking for expertise. If a book is about geology, I want to know if you’re a geologist. Same with fiction and an MFA.

What else matters?

Flashman: Like all agents and editors, I want a novel that, as one of my writers said, “has blood in it.” I want a novel that’s very deeply felt and urgent. I went to a PhD program almost right out of college and realized very quickly I did not want to be an English professor. There’s a tendency among writers to go straight into an MFA program, and for some writers, like Téa Obreht, it’s great. She had a great story and something urgent to tell. But a lot of writers don’t know their story yet. It might not surface till later.

Habib: I was a publicist before I became an agent, and when we’d have to publicize novels, the goal for fiction was always to develop a nonfiction hook. That’s the stuff that you can talk about in interviews, and it can develop naturally with writers who have life experience. When a book lands at a publisher and the writer has had a world of experience and can talk from a place of knowledge, that’s gold. That gets publishers excited to publish a book well.