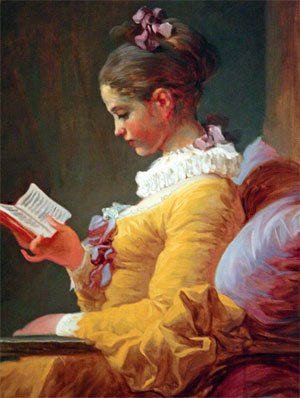

For the past few months, literary writers, editors, and critics have been using some strong adjectives while discussing To Read or Not to Read, a report released last November by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). “Scary,” “sad,” and “downright depressing” have been common responses—and for good reason. Reading in America is in serious decline, according to the NEA, especially among the young. Fewer than one-third of thirteen-year-olds read for pleasure every day—a 14 percent decline from two decades ago—while the percentage of seventeen-year-old non-readers doubled over the same period. Americans between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four watch television about two hours a day, the study reveals, but read for only seven minutes.

These and other findings in the report—which confirmed and expanded upon those previously published in Reading at Risk, the 2004 NEA survey indicating that Americans were reading fewer books of fiction, poetry, and plays—have obvious implications for writers, both in terms of the audience and market for their work and, more generally, for literature’s lasting impact on American culture.

Whereas Reading at Risk focused mainly on literary reading trends, culling information from a survey of more than seventeen thousand people aged eighteen and older about their consumption of novels, short stories, poetry, and plays, To Read or Not to Read gathers statistics from more than forty national studies on the overall reading habits of children, teenagers, and adults, and includes all varieties of reading, including books, magazines, newspapers, and online reading.

Both studies, however, come to the same grim diagnosis: There is a general decline in reading among teenage and adult Americans.

“The odd thing is that there’s no lack of writers,” says Donna Seaman, associate editor of Booklist, the review journal of the American Library Association. “I see hundreds of books every week—beautifully crafted, deeply felt works of fiction and poetry—and yet people are reading less. Everyone wants to write, no one wants to read; the disconnection is startling. That’s a real puzzle and a real challenge for creative writers in particular. I think we’re in danger of becoming a lost art, a lost world, if we’re not awakening the love of reading in young people.”

Novelist Audrey Niffenegger, author of The Time Traveler’s Wife

(MacAdam/Cage, 2003), agrees: “When you hear things like this, your

stomach kind of falls and you think, ‘We’re headed for perdition.’”

“It makes me very concerned that serious reading is becoming such a

specialized endeavor that it’s completely separate from the culture,”

says Christian Wiman, the editor of Poetry magazine, whose book of

essays, Ambition and Survival: Becoming a Poet, was published by

Copper Canyon Press last year. But Wiman realizes that no matter how

overwhelming the problem may seem, quiet resignation is not an

appropriate response. “I don’t think it’s always been that way,” he

continues, “and I don’t think it’s a foregone conclusion that it has to

be that way. I’ve heard people say, ‘You can’t resist the current, you

can’t resist the times.’ But you do have to resist the currents of the

times when they’re negative. These declines in reading are real, and

something has to be done.”

But what? Teachers shoulder much of the burden of improving reading

skills among students, but the new NEA report suggests that parents can

play an important role by reading to their children and modeling the

habit. Other strategies might arise as we begin to understand another

reason why young people are reading less—one that is more complicated

than the notion that they’re simply watching too much TV or spending

too much time surfing the Internet. According to Timothy Shanahan, a

professor at the University of Illinois, Chicago, and past president of

the International Reading Association, many young people don’t read

because, they say, it’s lonely.

“What kids like about [instant messaging] and text messaging is that

it’s playful and interactive and connects them to their friends,”

Shanahan says. “The Harry Potter books were popular not mainly because

of this wonderful story and the language, I don’t think, but because it

was this huge phenomenon that allowed young people to participate in

it. What was exciting was reading what your friends were reading and

talking to them about it. People of all ages are hungry for that kind

of community.”

The NEA seems to agree, pointing to the Big Read, its national program

in which communities around the country are reading American novels

such as Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence and Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck

Club. Similarly, a year after Reading at Risk was released the Poetry

Foundation partnered with the NEA to organize Poetry Out Loud, a

program in which students memorize and recite poems as a way to forge

connections to poetry. And book clubs, from the Oprah Winfrey

juggernaut to small neighborhood gatherings, continue to gain momentum.

But some say another fundamental factor in the decline of reading must

also be addressed: contemporary writers themselves, who have a

critical role to play if current trends are to be reversed. “I do think

for a long time writers turned completely away from the audience,”

Wiman says. “You can’t simply go back to the past, of course, but I do

think writers have to be aware of an audience.” Niffenegger points

specifically to modernism as a wedge between writers and readers.

“There was a shift away from narrative, where writers gave you less and

less and made you work harder and harder. People got the idea that

everything was going to be like Finnegans Wake, and everybody just

said, ‘Okay, we’re going to the movies.’”

Still, not everyone foretells the apocalypse. Tree Swenson, the

executive director of the Academy of American Poets, insists that all

signs point to an increased interest in poetry in America, particularly

online. “The Internet is a well-matched medium for poetry, in part

because the unit of consumption isn’t the book of poetry—it’s a single

poem, short and compact,” she says. “The Web and e-mail have also

facilitated people sending poems to one another. Yes, the larger trends

are disheartening, but if I can come back to poetry, I can find my

thread of optimism.”

To Read or Not to Read has the potential to inspire positive change.

“On the surface, the study would seem to be bad news for aspiring

writers, because you have the impression that the audience base is

depleting,” says Sunil Iyengar, the NEA’s director of research and

analysis. “On the other hand, there’s a tremendous opportunity for

meaningful interactions that can arise from the data. Booksellers,

publishers, teachers, librarians, businesses all have a common interest

in increasing reading because it exalts their mission. But it also

presents an opportunity for writers. By writing well, you’re filling

not only a market need; you’re raising the whole level of cultural

discourse in this country, because right now the bar is relatively low.

Writers could be taken more seriously than ever if people heed the

results of the report.”

To read the full report, visit the NEA’s Web site at www.nea.gov.

Kevin Nance is the critic-at-large at the Chicago Sun-Times.