On Wednesday, April 9, five months after his death at age eighty-four from acute renal failure, hoards of literary aficionados, friends, colleagues, and readers of Norman Mailer attended a memorial for the author at Carnegie Hall in New York City. Among the scheduled speakers were authors Don DeLillo, Joan Didion, and William Kennedy, actor Sean Penn, and members of Mailer’s family.

I learned about Norman Mailer in 1980 when, as a young woman, I read his controversial book The Executioner’s Song, a chronicle of the life and death of convicted Utah murderer Gary Gilmore. Mailer stirred something in me to write. But my first attempt—I wrote eighty-five pages, in pencil, about my own troubled childhood—dredged up so much emotional muck that I tucked it into a manila envelope and scratched Mailer’s name on it, hoping one day he would guide me to finish the book.

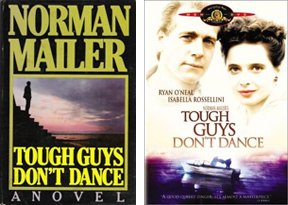

Six years later, our paths crossed again, this time in person, as we met by chance in Provincetown, Massachusetts, where Mailer was then dabbling in film as a screenwriter and director. He frequently spent the summers vacationing at his home on the tiny hook of seaside land at the end of Cape Cod. On Labor Day weekend, 1986, the sixty-three-year-old author was scouting for locations and background talent for the film adaptation of his novel Tough Guys Don’t Dance, starring Ryan O’Neal, Isabella Rossellini, and Lawrence Tierney.

For Bostonians the Cape was the place to be during any holiday. My brother and his friends shimmied on the dance floor of The A House, a darkly lit local bar where the pounding rhythms of the blaring music replaced your heartbeat. On the cramped dance floor we gyrated in a frantic sweat and passed around a small, dark-brown bottle of Poppers that spilled between our hands. One sniff of the amyl nitrate sent heat waves through our bodies and our hearts into overdrive, casting a yellow haze over the disco ball lights. Our short-lived euphoric laughter gave way to an aching jaw as the heaviness of reality reemerged.

It was then I noticed a man with an eight-millimeter camera on his shoulder shooting me while I danced. I figured he was with the Provincetown News taping the Labor Day festivities. He stood on the perimeter of the dance floor panning the dancers before focusing on me. There was another man with him—older, with thick, white, wavy hair and protruding ears. He approached and introduced himself. I strained to hear him over the music. With a forceful voice thick with a Brooklyn accent he announced, “Hello, I’m Norman Mailer. We’re shooting some footage for a movie I’ll be making. You have high energy. Is it alright if I shoot you for a party scene?”

“Okay,” I responded apprehensively.

He walked away and the cameraman stepped forward and filmed me as I camped it up. The man who I thought could only be an impostor—certainly not my literary idol—returned with a white cocktail napkin and pen, handed it to me, and asked for my name. “Would you sign your name on this napkin permitting me to use this footage?” he asked. I took the pen and napkin. I noticed there was something already scrawled on it. As I cocked my head, tilting the napkin towards the light to read it, his voice barreled over the music: “It states that you release to me what we taped. Your signature makes it a legal and binding document.”

I nodded and signed the napkin. He thanked me, smiled, and—like a man on a mission—turned to make his way out of the thickening crowd. I went back to my brother who was still dancing and shouted in his ear, “Is that Norman Mailer?” He bobbed his head to look above the crowd and answered, “I think so. It looks like him. Why?”

I described the strange scene to him, and as we moved off the dance floor, he stepped on something. When he reached down for the object, he pulled up a strip of eight-millimeter film that was strewn across the floor. “You’re already on the cutting room floor!” he cackled.

When the bar closed we walked up Commercial Street. Mailer was standing off of the sidewalk observing the stream of partygoers. I pointed him out to my brother who confirmed that it was indeed the esteemed author. I strutted over.

I asked what the movie was and how much longer he would be filming. He appeared open and replied in a husky tone from deep in his gut, “I’m making a movie from a novel I’ve written titled Tough Guys Don’t Dance. Have you ever been in a movie?” I replied that no, I hadn’t, and sheepishly added, “I tried writing an autobiography once, but stopped after eighty-five pages. I didn’t want to remember anymore.” He listened curiously as I told him more about myself.

I don’t know why I confided in him. I don’t know if he was interested or just being polite. I expected to be shunned, but for some reason it was important for me to bare my soul. I guess part of me was still searching for the father I lost as a child. The unconditional understanding Mailer had for a strange, young creature like myself had a profound impact on me. After I finished my story he inquired with a half-lit smile, “Would you like to be in my movie?” Without hesitation I gleefully answered yes. He must have seen the excitement in my eyes—my face aglow with hope.

His letters, notes, and doodles—the encouragement and advice that he sent to me over the last twenty-one years—still hang above my desk. His words helped me to become the writer I always wanted to be. “Don’t level off,” he once wrote to me, “The worse thing about leveling off in writing is when it begins to sink after a while. It could end up being tougher than anything you’ve ever done. But also, it could be the most enjoyable thing you’ve ever done.”

My paternal affection for him never waned, even after he begged me not to lipstick kiss the backs of the envelopes when I wrote—“since that just causes trouble with my wife,” he said. As a wise, elder, male figure, Norman provided what I, as a young, fatherless woman, sought. I grew up in his letters. I emptied my longings into the messages I wrote to him and asked for guidance as a young writer. In turn he advised me in my writing career and reluctantly critiqued works in progress. “As understood I don’t go in for critiquing pieces—I save all that for my own stuff like the greedy bastard I am,” he quipped.