The rain started on a Friday afternoon in early June. By the following Monday morning, up to ten inches had fallen on the lush, green fields of southern Wisconsin. Rivers crested several feet above normal, levees everywhere threatened to break, and dams strained against the deluge while residents of at least six small towns in the southwestern portion of the state were evacuated. The Kickapoo, a crooked tributary of the Wisconsin River that twists and turns from Wilton to Wauzeka, rose to twelve and a half feet, its water covering villages such as Gay Mills, Viola, and La Farge, where the residents of about fifty homes fled to higher ground. Forty miles to the east, Lake Delton, a 267-acre body of water that is a popular tourist destination, found a way around its dam and washed out Highway A, chewing a five-hundred-foot-wide channel to the Wisconsin River, which runs just seven hundred feet away. Within a few hours, seven hundred million gallons of water—and four well-appointed homes—surged into the river, leaving behind a muddy lakebed littered with boats, buckets, cinder blocks, and dead fish. On Tuesday, the Wisconsin State Journal announced the destruction on its front page (“A ‘CATASTROPHE’”) in letters an inch and a half tall.

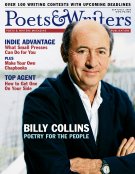

Novelist David Rhodes (Credit: Lewis Koch)

Nearly equidistant from the Kickapoo and Lake Delton, the Baraboo River meanders alongside the town of Wonewoc, whose eight hundred residents were spared heavy damage from the flooding, though portions of Highway Q were falling into the ditches as late as Tuesday afternoon. Novelist David Rhodes lives with his wife, Edna, on thirty-five acres of land about ten miles outside of the town, in the “driftless region” of Wisconsin, so named because its rugged terrain lacks the glacial deposits of rock, clay, sand, and silt—known as drift—that is typical of the state’s landscape. Looking at the Rhodes’s gravel driveway after the flooding, however, drift quickly comes to mind. More than nine inches of rain had washed down the jagged bluffs and hills, flowed through the valleys, and over their driveway, pushing hundreds of pounds of gravel across their front yard. From the shaded deck of his hundred-year-old wooden farmhouse, bejeweled with wind chimes, Rhodes looks out over the mess and considers aloud a fanciful plan to acquire from a local stonemason several life-size rhinoceroses and set them on the misplaced gravel with a sign that reads, Do Not Feed the Animals. Edna says this is not the first time he has voiced the idea.

Rhodes has seen this kind of flooding before—he’s lived in Wonewoc since 1972, and in recent years his front yard has resembled a riverbed on more than one occasion. When he moved there from Iowa City, where he had been a student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, his first novel, The Last Fair Deal Going Down, had already been published by Atlantic-Little, Brown. Within two years of his moving to Wonewoc, his second novel, The Easter House, was published by Harper & Row, its appearance compared by one New York Times critic to the publication of Sherwood Anderson’s classic Winesburg, Ohio; within three years, his third, Rock Island Line, which eventually would be lauded by the legendary novelist John Gardner, was published by Harper & Row; within four years, his first wife was pregnant with his first child, a daughter; and within five years, a horrifying motorcycle accident broke his back, paralyzed him from the sternum down, threw his marriage into a tailspin from which it would not recover, and all but erased his name from contemporary literature for the next three decades, his books quietly falling out of print, forgotten.

Through it all, Rhodes has continued to write. He is indifferent about the business of publishing, immune to the imperative of making his work known, downright shy of the limelight. But the act of writing...well, that’s a different story. Much more than a habit, far deeper than a discipline, writing is nothing less than his salvation. “It gives me a certain amount of peace,” he says. So, when a college student in Grand Rapids came across Gardner’s mention, in his seminal book On Becoming a Novelist, of Rhodes’s perfectly focused eye for detail, starting a chain of minor events that led a young editor from the Minneapolis-based independent press Milkweed Editions to come knocking on the writer’s door, Rhodes was ready with something to show, and then some. This month he is back after a thirty-three-year silence with a masterful new novel, Driftless.

Populated by an entire community of characters—the humble dairy farmers Cora and Graham Shotwell who rally against mysterious corporate forces; Violet Brasso and her sister, Olivia, a paraplegic who suddenly regains the use of her legs; Rusty Smith, a hard-working retiree who confronts his prejudices about the Amish; and Winifred Smith, a pastor at the local church who finds enlightenment where she least expects it—Driftless explores the uncommon connections that are forged, often unwittingly, between private people. Running throughout the novel is the story of July Montgomery, the main character of Rock Island Line, a vagabond who arrives in the small town of Words, Wisconsin, either to find a home where he can feel a part of other people’s lives, or die trying.

![]()

In the midst of our seven-hour talk on that waterlogged Tuesday in June, David Rhodes stops occasionally to recall an obscure name or date. He lowers his head slightly, closes his eyes, and assumes the look of a man opening a small jar of food for a child, as if the act of remembering, though not terribly difficult, is not something to be taken lightly. He may hold that expression a beat or two longer than one might deem comfortable, until he recalls what is needed, but the hush lifts as he again fixes his deeply kind, compassionate eyes on his conversant and continues. His ability to articulate his intended meaning is impressive, but then he has always chosen his words carefully.

Rhodes grew up on the northeast edge of Des Moines in the late forties and fifties, the second of three sons. His father was a pressman at the Des Moines Register, his mother a birthright Quaker, a preacher’s daughter who taught second graders at a local school. “Despite the fact that I lived outside of a big town I had kind of a provincial upbringing,” he says. “You could go three hundred yards in one direction and be in a corn field; you could go about a half mile in the other direction and be in the city.” Neither of his parents had a college education, but Rhodes says his mother pushed reading and religion above all; great literature, the Bible included, was omnipresent. At age fourteen, Rhodes was sent to Scattergood Friends School, in West Branch, about 125 miles east of Des Moines. Scattergood, founded in 1890 by Iowa Wilburite Quakers to provide a “guarded education” for their own children, was strict—and small. Rhodes was one of twelve kids in his graduating class.

After boarding school, in 1965, Rhodes moved north and attended Beloit College, on the southern edge of Wisconsin. He had planned to study science, but with eclectic interests and a restless spirit, he took classes in psychology, philosophy, and literature along with physics, chemistry, and calculus. “Those were real tumultuous times,” Rhodes says of the mid-sixties. “The culture was changing. They wanted to run the school like it was the fifties, and the students were ready for something different.” Rhodes was ready for something different too. Having lived first under the watchful eye of his mother and then within arm’s length of her religious strictures at Scattergood, arriving at Beloit felt to him like being cut loose. “It was in some ways overwhelming. I didn’t have the discipline to stick hardly with anything. Every time I turned around another good-looking girl would walk by, and I fell in love very easily. I was a real romantic, and everything meant a lot.”

After a year and a half, Rhodes quit school and moved with his girlfriend to Philadelphia, where he worked at a factory mixing chemicals, some of which ended up in hospitals in Vietnam. (Rhodes had been a registered conscientious objector since he was eighteen; years later, when he was called up for a physical, a doctor declared him unfit for service due to anxiety, though Rhodes believes he just took one look at him and determined he wasn’t cut out for it: “He talked to me and he said, ‘Why are you so nervous?’ And I said, ‘I’m not nervous.’ And he said, ‘You seem awfully nervous,’ and I said, ‘I’m not nervous,’ and he said, ‘Well, I’m sorry but we’re going to find you unfit for military service.’ And I said, ‘Well, that’s okay with me’ So that was the end of that.”) City life was exciting—Rhodes recalls frequenting bars in which men carried guns and there were bullet holes in the walls—but he quickly realized it wasn’t for him. “I would get up in the morning and I would go outside and I would think, ‘I’m living here—what am I doing here?’” So he left his girlfriend, moved to Vermont, and attended Marlboro College, where he majored in contemporary literature, reading 150 books, by his count, during his last year there. It was 1969. He was twenty-three years old and he had already met the woman who would become his first wife and started to write the manuscript that would become his first novel. He completed forty pages or so, sent it to the Writers’ Workshop, and was accepted. Back in Des Moines, his mother, having been diagnosed with cancer years earlier, died at the age of fifty-two.

“She was the center. My mother was the intellectual and the emotional center of that home,” Rhodes says. “It’s always traumatic to lose your mother. It was a formative event because it happened at a period in my life when I was just graduating from college, and it helped to collect me, I guess. I was very rebellious when I was younger—it was a source of much anguish for her—and when she died it seemed like, ‘Well, maybe I don't need to do that anymore.’ My mother presented a good force to push against. And without the force there, it was like, ‘Okay, that’s enough of that.’”

Still grieving for his mother, Rhodes went to graduate school. The Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1969 was much like it is today: Priority is placed on time to write and to socialize with other writers. Students tend to spend their days creating art and their nights establishing connections in support and service of that art. Rhodes did the former, but not the latter. He spent his time in Iowa City writing the rest of The Last Fair Deal Going Down and working nights at the Oakdale Alcoholic Center (where the late Richard Yates, who taught at the Workshop in the sixties and early seventies, sought treatment). He rarely mingled with the other writers.

“I didn’t understand what I was supposed to be doing there,” Rhodes says. “I can see now that what I should have been doing is making contacts and meeting people, and I didn’t do any of that. I went there and I found an abandoned farmhouse and I put a roof on it and I thought, ‘Wow, now I can write.’ There were classes like once a month that you could go to, and I went to those and I never saw anybody. I went to the other English classes too, but basically I just wrote. I thought, ‘This is the time to write,’ and that’s what I did, so when I came out of there I knew a couple people, but most of them I’d never met.”

He did make at least one connection at Iowa. Joe Kanon, a young editor from Atlantic-Little, Brown (who years later would become executive vice president of Houghton Mifflin), was visiting the campus scouting for new talent. He asked Rhodes what he was working on and, upon hearing the premise of the novel—a tale of two cities: Des Moines, home to the Sledge family, a seedy lot of characters fathered by a railroader who drinks himself to death on a dare; and a metaphorical “City” built by religious fanatics at the bottom of a gigantic hole in the ground and teeming with cannibalistic heroin addicts too paralyzed by religious guilt to escape—he told Rhodes to send him the manuscript. He did, and Kanon bought it. Rhodes hadn’t yet received his MFA, had never received a rejection—had never even submitted his work—and he had a book deal with a major East Coast publisher. He received a two-thousand-dollar advance, which Rhodes figured he could live on for twelve months or more.

After graduation, Rhodes stayed in Iowa for another year, got married, finished his second novel, and started writing his third. In late 1972 he moved to Wonewoc. He had a master’s degree, he was a published author, his future was bright. He was twenty-six years old, and he drove a fast motorcycle.

![]()

There are many reasons why someone might disappear. That was what Ben Barnhart thought when an online search turned up the phone number and address of David Rhodes. It was the summer of 2004, and Barnhart, then a fledgling editor at Milkweed Editions, had received one of those “You Have to Read This” missives from his friend Phil Christman. “I ran across Dave’s name in John Gardner’s On Becoming a Novelist back when I was in college, about ten years ago,” says Christman, who is now a student in the MFA program at the University of South Carolina in Columbia. ‘‘Gardner cites him as having ‘one of the best eyes in recent fiction,” which in Gardner’s lexicon means not just that he’s a good observer but that he has a take on the world that seems fresh, underivative, compelling.” Years later, having finally found Rhodes’s novels in a library in Saint Paul, where he had been volunteering for AmeriCorps, Christman told his friend at Milkweed about his new favorite author.

“Being the reluctant person to take recommendations that I am, I sat on it for about three or four months before finally picking up Rock Island Line myself, but was then immediately pulled in by Dave’s writing, his ability to develop characters and his amazingly strong economy of language,” says Barnhart. “Together, Phil and I were bemoaning the fact that there were no new novels by this author. The last one was published in 1975 and nearly no one had ever heard of him. There were a handful of references that we’d run across online, but in general no one knew the story. His bio claimed he had lived in Wisconsin, so we did a white pages search on the guy and it turned up an address. It was that moment that gave me a lot of pause, because I had no idea what had happened to Dave other than that he had written three amazing books and then disappeared. I thought, ‘Maybe he doesn’t want to come back out into the world; maybe something happened.’”

Rather than call Rhodes out of the blue and ask, “What have you been doing with the last thirty years of your life?” Barnhart did some more digging around and discovered that Rhodes had been represented by Lois Wallace, who before meeting the author in the early seventies had left the William Morris Agency and started Wallace, Aitken & Sheil. (When Kanon left Atlantic-Little, Brown following the publication of Rhodes’s first novel, Rhodes’s new editor didn’t take to his second book, so he suggested he meet Wallace, who signed him—shortly after she signed Don DeLillo; White Noise is dedicated to her—and subsequently sold The Easter House and Rock Island Line to Harper & Row.)

“At this point I was thinking that being in touch with Dave was more like sending a glorified fan letter,” Barnhart says. “I wrote to Lois and didn’t really expect to hear anything from her soon, if at all. But then about a week later I got a call from her.” Wallace told Barnhart she hadn’t thought of her long-lost client for years but that, prompted by his letter, she’d e-mailed him and discovered that, yes, he was still alive, still writing. (Rhodes says he very nearly didn’t receive that e-mail, which had landed in his junk mail folder.)

Encouraged by Wallace’s quick response, Barnhart and Christman wrote a letter to Rhodes and asked if they could visit. “He was very gracious. He said, ‘My wife and I would love to have you come,’” Barnhart says. “Events began to transpire quickly with an agent involved.” Even before Barnhart traveled to Wonewoc, Wallace encouraged Rhodes to send the editor the novel he’d been working on, Driftless. In June 2005 he did, signing his cover letter:

I know Midwesterners are accused of talking too much about the weather, but that criticism must surely come from people who don’t have weather like ours. These last few weeks have been filled with the bright, indolent humidity of summer, offset by sudden, tyrannical darkness and booming threats of supernatural violence. Not mentioning such revolutionary experiences would be inhuman.

I hope you are well and look forward to meeting you.

Yours truly,

Dave

![]()

David Rhodes is talking about fate. He holds his strong hands out in front of his chest, cupping them carefully, as if he’s hiding something fragile—an egg, or a newly hatched bird. “Our view in physics is that when you have two particles that are coming together they are unrelated to each other, but that after they interact their movements can be explained through that interaction, because one will have a certain momentum in this way and the other in this way. And then it makes sense that they have this relationship that comes back to here,” he says, moving his hands quickly apart, then slowly back together again. “But if you reverse the arrow of time, then all of a sudden you see they were related from the beginning and it’s just a myth that we tell ourselves that they were completely autonomous and unrelated as they come together. Experience comes to us as a whole, and to understand it intellectually we pull it apart and we separate one from the other in that process of abstraction. But the experience is always bigger than the understanding of that experience.”

Rhodes has spent a long time trying to understand and come to terms with what he experienced one day in the spring of 1977, and every day since then. He had been living in Wonewoc for five years, his third novel had been published to enthusiastic reviews, and his wife had given birth to a girl, Alexandra, just two weeks earlier. Gone were the unmoored days of his youth when he rebelled against his provincial upbringing. Gone were the Iowa City hours of writing in his abandoned farmhouse. Gone, too, was the motorcycle that Rhodes had ridden ever since he was old enough to drive—he had given it to a neighbor a few months before his daughter was born. He had become afraid of it, he says; he had started taking too many chances. He had new responsibilities now: He had a baby to think about.

Then came the premonitions. There were dreams in which he was paralyzed, doctors poking needles in his body. Then there was an incident at the Sauk County Health Care Center, where Rhodes worked the night shift, looking after thirty or forty elderly men. One night, he confronted a man who wouldn't go to bed. “He was in the common room down there in the middle of the night and he kept telling me over and over again, he kept saying, ‘Do you hear that noise?’ And I said, ‘No, I don’t hear the noise, you gotta go to bed.’ ‘That’s a motorcycle,’ he said. ‘Do you know how dangerous motorcycles are? Do you know how careful you have to be on them?’ And I kept saying, ‘No, you gotta go to bed.’ And that was the night before it happened.”

After months of trying to get it started, the neighbor to whom Rhodes had given his motorcycle finally succeeded, and drove it over to show Rhodes, who decided to take it for one last ride. “I was driving too fast, the bike went down. I hit a rock in the ditch and I flew up in the air and landed on my back and I was paralyzed from that moment on.” Rhodes spent nearly two years in a hospital in Madison, about eighty-five miles southwest of Wonewoc; his wife and daughter stayed in an apartment nearby. When he was released, the three of them moved back home.

But less than a year later his wife and daughter moved out, this time for good. By then Rhodes was addicted to the morphine doctors had prescribed for the phantom pains he was experiencing throughout most of his body. “It was a difficult, dark period of time,” he says. “I wrote a number of things, and I put a minimal effort into seeking publication for them. I used the first rejection as a reason not to pursue it any further, because I was profoundly unhappy with myself and I was profoundly unhappy with the writing I was doing. It was a long period of writing novels that were very long and very dark. I don’t think I’ll ever want to see anything ever done with those. I was working through things in a way that I didn’t have enough of a vision. And I was too angry and I was too bitter.”

By 1982 (the same year, coincidentally, that John Gardner was killed in a motorcycle accident), Rhodes had weaned himself from the drugs and met the woman who would later become his second wife—Edna, a school psychologist whom Rhodes describes, simply, as an angel. The two have a daughter, Emily, who recently graduated from the University of Chicago with a degree in public policy. During our conversation, Edna moved quietly in and out of the house, at one point driving to a neighboring farm to get a chicken to roast for our meal that evening (she told us the woman who sold it to her had to wade across a small river in order to hand it to her) and to pick up a package of madeleines from a French nun who didn’t speak English. As we nibbled on that most literary of snacks (Rhodes counts Proust among his favorite authors—him and Faulkner), he spoke more about his relationship to writing.

“Once I discovered writing as a young man it was something I needed to do in order to cope with myself. I didn’t feel sane unless I was writing. Writing gave me a way of focusing on my experiences that allowed me a certain level of equanimity, and without it I didn’t have that. If I don’t write I don’t feel right. It always offered me a way to be able to calm my mind and to keep from becoming depressed and to basically understand myself and work through difficulties.”

Despite this rather therapeutic approach, Rhodes does not write directly about his life. While all four of his novels have traces of autobiography—Des Moines as a birthplace of unshakable psychic weight (The Last Fair Deal Going Down), a grandfather who was a preacher (The Easter House), a teenager’s escape from the Midwest to Philadelphia and back again (Rock Island Line), and a small Wisconsin town that is at once a bastion of solitude and a tightly woven community (Driftless)—Rhodes has never written about himself and probably never will. Instead, he projects onto his fictional characters in a way that allows him to see himself and his experience from a distance. “Through writing it feels like I’m participating in something meaningful—a dialogue.”

![]()

David Rhodes’s new novel, which is being published simultaneously with a new paperback edition of Rock Island Line, is reason to celebrate. There is nothing so affirming, so inspiring, as holding in your hands the black-and-white, spelled-out proof that an author who writes because he wants to write—because he must write, not because he wants to get published—who after tasting the kind of success that so many young writers thirst for then lived the next three decades in recurring pain and obscurity, has not lost one ounce of the mastery for which he was recognized in the first place.

A friend recently told Rhodes that he was the strongest person he’s ever known, an assertion that the writer quickly dismissed. “I have been so fortunate with people being there,” he says. “When I needed someone there, someone would be there. So many times in my life I’ve just thought, ‘This is the end,’ and somebody from nowhere comes and says, ‘No, this isn’t the end.’ Every day I’m thankful for it.”

Rhodes is currently working on several projects, one of which is a novel about the life of King Herod, though it has been slow going. He will almost certainly delve into it as his reentry into the world of publishing progresses. He’s not one to bask in the limelight, even if its warmth is long overdue. “I’m still feeling overwhelmed by all the attention,” he wrote in an e-mail, “which in some ways resembles the recent flooding.”

As for the water that washed over Wonewoc, then continued to wreak havoc on parts of the upper Midwest, Iowa in particular, and in just about every state through which the Mississippi River flows, Rhodes wrote, “The water has receded in Wisconsin, and aside from an occasional puddle here and there, many landscapes have apparently decided to retain no visible signs of the crisis. Only in memory.”

Kevin Larimer is the deputy editor of Poets & Writers Magazine.