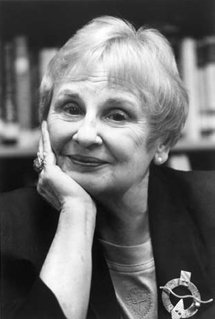

Against a backdrop of snowfall and accompanied by the jazz strains of “A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square,” a memorial service for the legendary W. W. Norton editor Carol Houck Smith, who died late last year at the age of eighty-five, was held recently at St. Peter’s Church in New York City. The evening service featured remarks by Norton leadership past and present as well as authors Andrea Barrett, Charles Baxter, Ron Carlson, Joan Silber, Gerald Stern, Brady Udall, and Ellen Bryant Voigt. Poets Rita Dove, Maxine Kumin, and Stephen Dunn contributed remarks in absentia.

Senior editor and poet Jill Bialosky read Dove’s remembrance that “a German word came to mind” whenever she was with Smith, whose German heritage and Buffalo roots were frequently employed to characterize her. “The word is engagiert, which means ‘engaged,’ as in being engaged in work on a task or a pet project. The German word implies a bit more passion than mere interest; the object of one’s dedication is the object of one’s affections as well.”

Writers who had worked with Smith remembered her commitment to their career advancement, her generous approach to teasing out talent, her sense of humor, and “the girl in the lady,” a phrase that Baxter used to describe an aura of youth that endeared her among men and women alike.

Baxter recalled a “less official person in whom the qualities of willpower, shrewdness, flirtatiousness, and charm were all…confusingly mixed. If you were an eligible or even an ineligible male, you’d discover that one minute she’d be fixing one of your sentences, and the next minute she’d be batting her eyelashes at you, or patting her hair in the back with that endearing gesture she had.”

Smith’s sixty-year rise at Norton, from secretary to vice president, was capped by a working retirement as editor at large that proved to be one of her most rewarding periods. At the time of her death, she was editing a new collection of poetry by Dove, among other books.

Speakers described her as “sprightly,” “shrewd,” “frank,” and, according to Starling Lawrence, “a pistol.”

“She stood up for me,” said an emotional Carlson, who recalled Smith’s tendency to deliver reviews personally, by phone.

“She was a dove,” said Stern.

Voigt closed the service with a reading of “The Long Boat,” a poem by the late Stanley Kunitz, who, at the age of eighty-seven, was offered a now famously optimistic three-book deal by Smith. (“Peace! Peace! / To be rocked by the infinite! / As if it didn’t matter / which way was home....”)

The event was followed by a reception where everyone received small stones that had been found throughout Smith’s apartment—souvenirs from her travels.

Warmed by a glass of wine but no less conscious that my debut poetry collection, Yellowrocket, had been published as a Smith discovery just two weeks before her death, I confessed to Baxter that I felt inadequate to the history in the room.

“We all do,” he replied.