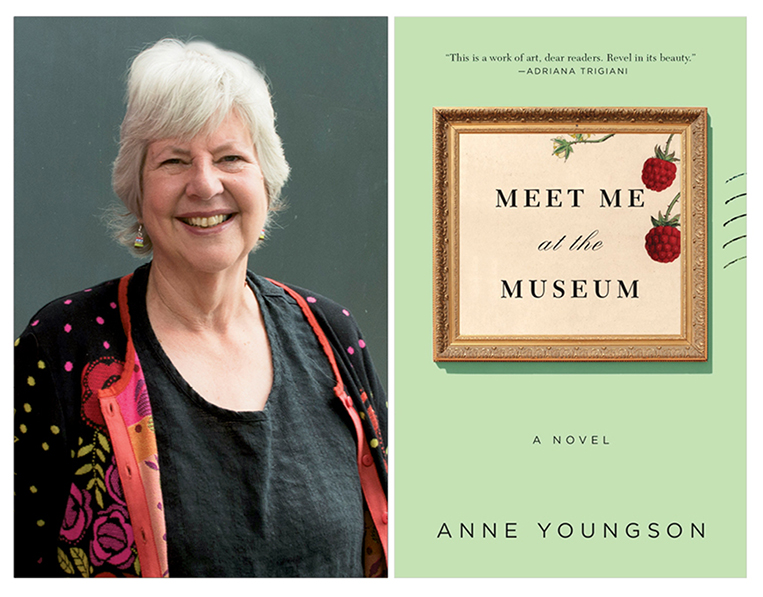

Anne Youngson, author of Meet Me at the Museum, published in August by Flatiron Books.

Dear young girls,

Home again from the deserts and oases of the Sheikdoms I find your enthusiastic letters on my desk. They have aroused in me the wish to tell you and many others who take an interest in our ancestors about these strange discoveries in Danish bogs. So I have written a “long letter” in the following pages for you, for my daughter Elsebeth, who is your age, and for all who wish to learn more about ancient times than they can gather from the learned treatises that exist on the subject. But I have all too little time, and it has taken me a long while to finish my letter. However, here it is. You have all grown older since and so perhaps are now all the better able to understand what I have written about these bog people of 2,000 years ago.

Yours sincerely,

P. V. Glob (Professor)

August 13th, 1964

An extract from the foreword to The Bog People, by P. V. Glob (Faber and Faber, 1969): Professor Glob responds to a group of schoolgirls who have written to him about recent archaeological discoveries. The Bog People is dedicated to these schoolgirls.

Bury St. Edmunds

November 22

Dear Professor Glob,

Although we have never met, you dedicated a book to me once; to me, thirteen of my schoolmates, and your daughter. This was more than fifty years ago, when I was young. And now I am not. This business, of being no longer young, is occupying much of my mind these days, and I am writing to you to see if you can help me make sense of some of the thoughts that occur to me. Or maybe I am hoping that just writing will make sense of them, because I have little expectation that you will reply. For all I know, you may be dead.

One of these thoughts is about plans never fulfilled. You know what I mean—if you are still alive you must be a very old man by now and it must have occurred to you that what you thought would happen, when you were young, never did. For example, you might have promised yourself you would try a sport or a hobby or an art or a craft. And now you find you have lost the physical dexterity or stamina to take it up. There will be reasons why you never did, but none of them is good enough. None of them is the clincher. You cannot say: I planned to take up oil painting but I couldn’t because I turned out to be allergic to a chemical in the paint. It is just that life goes on from day to day and that one moment never arrives. In my case, I promised myself I would travel to Denmark and visit the Tollund Man. And I have not. I know, from the book you dedicated to me, that only his head is preserved, not his beautiful hands and feet. But his face is enough. His face, as it appears on the cover of your book, is pinned up on my wall; I see it every day. Every day I am reminded of his serenity, his dignity, his look of wisdom and resignation. It is like the face of my grandmother, who was dear to me. I still live in East Anglia, and how far is it to the Silkeborg Museum? Six hundred miles as the crow flies? As far as Edinburgh and back. I have been to Edinburgh and back.

All this is not the point, though it is puzzling. What is wrong with me that I have not made the so small effort needed when the face of the Tollund Man is so central to my thoughts?

It is cold in East Anglia, windy cold, and I have knitted myself a balaclava to keep my neck and ears and head warm when I walk the dog. As I pass the mirror in the hall on the way out of the door, I notice myself in profile and I think how like my grandmother I have become. And, being like my grandmother, my face has become the face of the Tollund Man. The same hollowness of cheek, the same beakiness of nose. As if I have been preserved for two thousand years and am still continuing to be. Is it possible, do you think, that I belong, through whatever twisted threads, to the family of the Tollund Man? I’m not trying to make myself special in any way, you understand. There must be other people of the family, thousands of them. I see other people of my age, on buses, or walking their dogs, or waiting for their grandchildren to choose an ice cream from the van, who have the same contours to their faces, the same blend of peacefulness, humanity, and pain. There are far more who have none of these things, though. Whose faces are careless or undefined or pinched or foolish.

The truth is, I do want to be special. I want there to be significance in the connection made between you and me in 1964 and links back to the man buried in the bog two thousand years ago. I am not very coherent. Please do not bother to reply if you think I do not justify your time.

Yours Sincerely,

T. Hopgood (Mrs.)

Silkeborg Museum

Denmark

December 10

Dear Mrs. Hopgood,

I refer to your letter addressed to Professor Glob. Professor Glob died in 1985. If he had still been alive, he would by now be over 100 years old, which is not impossible, but is unlikely.

I believe you are asking two questions in your letter:

i. Is there any reason why you should not visit the museum?

ii. Is there any possibility you are distantly related to the Tollund Man?

In answer to the first, I would encourage you to make the effort, which need not be very great, to visit us here. There are regular flights from Stansted, or, if you prefer, from Heathrow or Gatwick, to Aarhus airport, which is the most convenient for arriving in Silkeborg. The museum is open every day between 10 and 5. Here you can see the Elling Woman as well as the Tollund Man, and an exhibition that looks at all aspects of those who lived in the Iron Age; for instance, what they believed in, how they lived, how they mined and worked the mineral that gives the period its name. I must also correct something you said in your letter. Although only the head of the Tollund Man is preserved, the rest of the body has been recreated, so the figure you will see, if you visit us here, will look just as it did when it was recovered from the bog, including the hands and the feet.

In answer to your second question, the Center for GeoGenetics at our Naturhistorisk Museum is at the moment trying to extract some DNA from the Tollund Man’s tissues, which would help us to understand his genetic links to the present-day population of Denmark. You will have read, in Professor Glob’s book, that the index finger of the Tollund Man’s right hand shows an ulnar loop pattern that is common to 68 percent of the Danish people, which gives us confidence that this study will find such links. Through the Vikings, who came later to Denmark but will have interbred with the existing population, there is most likely some commonality of genes to the population of the UK. So, I would say, it is quite possible that there is a family connection, however slight, between yourself and the Tollund Man.

I hope this information is helpful to you, and look forward to meeting you if you visit us here.

Regards,

The Curator

Bury St. Edmunds

January 6

Dear Mr. Curator,

It was generous of you to reply to my letter to Professor Glob, and to try to answer what you understood my questions to be. But they were not questions. The reason I have not visited has nothing to do with the problems of travel. I have passed my sixtieth birthday but am nonetheless quite fit. I could go tomorrow. There have been few times in my life when that has not been so. Leaving aside child birth and a broken leg, I have always been physically able to climb onto a plane, or indeed a ferry, to Denmark.

This being the case, I am forced to consider what might be the real reasons, because your answer to an unasked question has made me want to be honest with myself. Please be aware, I am writing to you to make sense of myself. You do not need to concern yourself with any of this. I do not expect you to reply.

My best friend at school was called Bella. This was not her given name and is not the name in Professor Glob’s dedication: it is a nickname, based on her ability to pronounce Italian words. She was rubbish at languages, as far as learning to use them to communicate was concerned, but she could act them beautifully. Her favorite word was bellissima. She was able to put a level of meaning into each syllable that varied according to the context, so the word seemed to mean more, when she said it, than it actually does. In fact, everything she said had more meaning, more intensity, than the same words used by anyone else.

We were friends from the first day we met, which was our first day at school. She was more colorful than I was; adventurous, alive in the moment. She brought me energy and confidence, and I loved her for it. What she loved about me, I think, was the steadiness. I was always there, always had a hand ready to hold hers. We were friends all our lives. All her life, for I am still alive, as you know, and she is not. And all our lives we talked about the time when we would visit the Tollund Man. We were, you see, always going to do it, but not yet. To begin with, we did not want to use up this treat before we had savored the looking forward to it. We were maybe, also, a little afraid that it would not be what we had hoped. We hoped it would be significant in some way—we could not have told you in what way—and there was a risk it would not be. Our school friends went, helterskelter. As soon as The Bog People was published in translation, if not before. They came back with an even stronger sense of ownership of the Tollund Man and Professor Glob and all things Danish than they already had. Bella and I thought they were superficial and unworthy and that the experience they had had was trivial, in comparison to the experience we would have. One day.

From Meet Me At the Museum by Anne Youngson. Copyright © 2018 by Anne Youngson. Reprinted by permission of Flatiron Books.