For the past five years we’ve dedicated this space to featuring five debut authors who have lived a good deal of life before publishing their first books. From the start our aim was to highlight not one path—not some mythical road, paved with youthful intentions, upon which so many “new and emerging” authors travel—but rather the countless individual routes, some considerably longer and circuitous than others, that lead to the publication of a debut book. After all, there isn’t one way to be a writer, and “new” and “emerging” are not synonymous with “young.” In this, our fifth annual 5 Over 50, we meet five authors—ranging in age, from early fifties to early seventies, and published by presses large and small, from Cleveland’s independent Belt Publishing to New York City’s Big Five imprints—who followed their passion, dedicated themselves to their craft, and pursued with dogged perseverance a dream undiminished by career building, child rearing, and the joys, sorrows, responsibilities, and challenges of lives well lived. As one of this year’s debut authors, A. H. Kim, whose dream to publish a book revealed itself relatively recently—only eight years ago—puts it: “To those of you who have a dream I say, ‘Go for it.’”

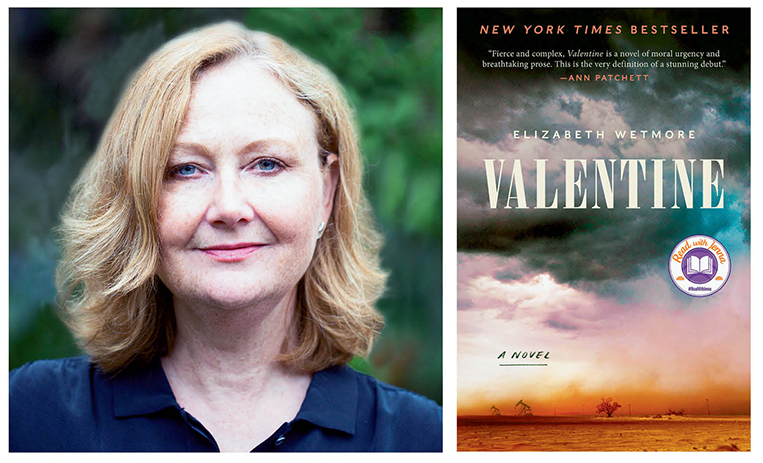

Valentine (Harper, March 2020) by Elizabeth Wetmore

The Last Children of Mill Creek (Belt Publishing, April 2020) by Vivian Gibson

A Good Family (Graydon House, July 2020) by A. H. Kim

We Were Lucky With the Rain (Four Way Books, September 2020) by Susan Buttenwieser

2nd Chance (New Issues Poetry & Prose, October 2020) by Daniel Becker

Elizabeth Wetmore, author of Valentine, published in March by Harper. (Credit: Carrie Allen)

I used to believe a person could teach herself to be merciful if she tried hard enough to walk in somebody else’s shoes, if she was willing to do the hard work of imagining the heart and mind of a thief, say, or a murderer, or a man who drove a fourteen-year-old girl out into the oil patch and spent the night raping her. I tried to imagine how it might have been for Dale Strickland:

The sun was already crawling toward high sky when he woke up, dick sore and dying of thirst, his jaw locked in a familiar amphetamine clench. His mouth tasted like he had been sucking on the nozzle of a gas can, and there was a bruise the size of a fist on his left thigh, maybe from hours pressed against the gearshift. Hard to say, but he knew one thing for sure. He felt like shit. Like somebody had beaten both sides of his head with a boot. There was blood on his face and shirt and boot. He pressed his fingers against his eyes and the corners of his mouth. Turned his hands over and over looking for cuts, then pressed them against the sides of his head. Maybe he unzipped and examined himself. There was some blood, but he couldn’t find any obvious wounds. Maybe he unfolded himself from the front seat of his pickup truck and stood outside for a minute, letting the harmless winter sun warm his skin. Maybe he marveled at the day’s unseasonable warmth, its unusual stillness, just as I had earlier that morning when I stepped onto my front porch and turned my face to the sun and watched a half dozen turkey buzzards gather in large, slow circles. The work of mercy means seeing him rooting around in the bed of his truck for a jug of water and then standing out there in the oil field, turning 360 degrees, slow as he could manage it, while he tried to account for his last fourteen hours. Maybe he didn’t even remember the girl until he saw her sneakers tumbled against the truck’s tire, or her jacket lying in a heap next to the drilling platform, a rabbit skin that fell just below her waist, her name written on the inside label in blue pen. G. Ramírez. I want him to think, What have I done? I want him to remember. It might have taken him a little longer to understand that he had to find her, to make sure she was okay, or maybe to make sure they were clear about what had happened out there. Maybe he sat on the tailgate, drinking musty water from his canteen and wishing he could remember the details of her face. He scuffed a boot against the ground and tried to bring the previous night into focus, looking again at the girl’s shoes and jacket then lifting his gaze to the oil derricks, the ranch road and railroad tracks, the scarce Sunday traffic on the interstate and behind that, if you looked real hard, a farmhouse. My house. Maybe he thought the house looked too far to walk to. But you never know. These local girls were tough as nails, and one who was mad? Hell, she might be able to walk barefoot through hell’s fires, if she made up her mind to do it. He pushed himself off the tailgate and squinted into the jug. There was just enough water to clean up a little. He bent down in front of the driver’s mirror and ran his fingers through his hair, made a plan. He would take a piss, if he could manage it, and then drive over to that farmhouse and have a little look-see. Maybe he’d get lucky and the place would be abandoned, and he’d find his new girlfriend sitting out there on a rotting front porch, thirsty as a peach tree in August and happy as hell to see him again. Maybe, but mercy is hard in a place like this. I wished him dead before I ever saw his face.

From the book Valentine by Elizabeth Wetmore. Copyright © 2020 by Elizabeth Wetmore. Reprinted courtesy of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.