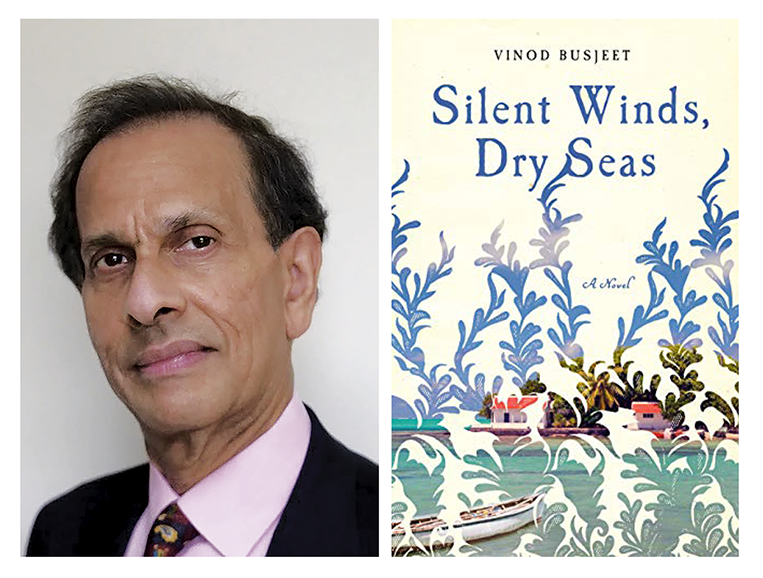

Vinod Busjeet, author of Silent Winds, Dry Seas, published by Doubleday in August 2021. (Credit: Sushant Sehgal)

After a night of howling winds and buffeting rain, we spent February 27, 1960, indoors, like most Mauritians. In the morning, a police car announced by loudspeaker that a Class 4 warning—the highest level of alert—had been issued. Cyclone Carol had swept Saint Brandon Island, three hundred miles northeast of Mauritius, and winds of at least 120 miles per hour would hit our island.

We were all anxious. All the precautions that could be taken had been taken. Throughout the day, the winds grew more violent and the rain more intense.

At dinnertime, Uncle Ram opened the bottle bought at la boutique Dokter. At eight thirty, the electricity went off. At around nine, he thundered, “Shiv, did you ask Vishnu what he thought of the Royal College?”

“He told me he liked it,” Papa replied.

“That boy is destined for England,” said Uncle Ram. “You wait and see: he’ll come back with an Englishwoman.”

Mama looked at Papa in a way that clearly signaled that he should respond firmly to this.

“Don’t talk like that. He is only ten,” Papa said.

“He has the brain of a fourteen-year-old.”

Auntie Ranee interjected: “Stop drinking and talking rubbish. People are worried about the cyclone.”

“Worried about the cyclone? The Bhushans and the community are worried about their purity. Vishnu, I have a better idea. Englishwomen are too boring for you—bring back a European. Brigitte Bardot or Sophia Loren. Shiv, did you hear what I said? That will improve the Bhushan stock and defile it.”

No one responded. The subdued light of the candles and hurricane lamps produced the mood of a vigil for Cyclone Carol, not one conducive to confrontation.

That evening, and for the first time since I lived in that house, Uncle Ram did not say his usual “Hawa baand, samoondar soukarey.” The last words he uttered as he went to bed were:

1945 1945 1945.

I don’t know if Auntee Ranee or Mama or Papa detected the same sentiment, or even paid attention, but I thought his voice was sorrowful. I went to bed feeling sad for him.

Outside, Cyclone Carol’s ire was turning to rage. I was afraid.

. . .

The next morning, February 28, 1960, at around 8:30, we heard a loud bang. It sounded like a huge sheet of metal hitting our house. This was followed by many more such bangs, of wood beams and shingles flying in the air and crashing on the road or against the neighbors’ houses. There was the eerie sound of trees being uprooted and crashing to the earth.

Suddenly Uncle Ram shouted, “Shiv, come here. I need your help.”

I followed Papa to Uncle’s living room. The front door was open and the cyclonic wind was pummeling with such force that Uncle and Papa couldn’t push the door shut. They couldn’t even reach the doorknob. Mama, Auntie, and I stood behind them, hoping that the human barrier thus created would prevent, or at least reduce, the wind whipping in. We looked at each other: we were sure Uncle Ram had forgotten to close the door when he went to bed. We remembered his drunkenness.

A loud creaking noise from above tore through my ears. I looked up. The wind blowing in through the open door was battering the gable roof from the inside. Planks were detaching from the beams.

Uncle Ram was exhausted. It was clear we were going to lose the front roof. As rain poured into the living room, Papa, Mama, and Auntie began to move an armoire to a room at the back, which had its own gable roof. On the mirrored doors of the armoire, I caught a shadowy glimpse of Lion Mountain. I turned my head: a window had flung open, revealing the mountain on the horizon. It looked like it never had before—desolate, dreary, no longer conjuring up the stately lion of sunny days.

“Run to the back,” Papa said.

I felt his hands grab my shoulder, then I spotted Uncle Ram’s stationmaster’s cap on the floor. It was his treasured possession, one he proudly displayed on the wall. I wriggled free, made a dash for it, and picked it up.

Another great bang sounded and the front roof was gone. Somehow it did not fall on the floor—Papa and I would have been crushed to death. It flew away from the house.

We huddled in the back. With the wind now banging inside the house, we saw and felt its fury—we were inside its fury, we were almost part of it. Papa yelled that Cyclone Alix, six weeks earlier, looked like a trial run. He and Uncle Ram decided we should lock the back and run to the neighbor across the road, the Prem family, who had just built a new house. Papa, being the strongest, would hold Auntie Ranee’s baby; Mama and Auntie Ranee would carry the jewelry and valuables; Uncle Ram would carry legal and bank documents; and I would run ahead of them so they could keep an eye on me.

We massed near the door, waiting. Papa felt a lull and told me to run, and the next thing I knew I had landed like lead under the custard apple tree. I tried to move, but I felt nailed to the ground. The velocity of the wind was such that the rain was moving horizontally. Like a mad magic carpet, a corrugated iron sheet from a neighbor’s roof swirled over my head, nearly decapitating me. I was terrified. Mama looked distraught. Papa shouted at me to wait. Uncle and Auntie were speechless. Then there was a true lull, and we all ran to the Prem family. The whole neighborhood, some thirty people spread across five rooms, had sought refuge there, nervously drinking tea and listening to the wind.

From Vinod Busjeet’s Silent Winds, Dry Seas. Copyright © 2021 by Vinod Busjeet. Used with permission of Doubleday.

Read Vinod Busjeet’s essay about writing Silent Words, Dry Seas in the November/December 2021 issue of Poets & Writers Magazine.