On the outskirts of Oslo, just beyond the point where the city dissolves into forest, one thousand spruce saplings reach feathery green fingers toward the sky. Just over ten years ago this clearing was just another part of Norway’s vast woodlands. Today these trees are destined to become part of a unique library of texts by beloved authors, a century in the making.

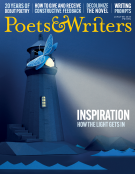

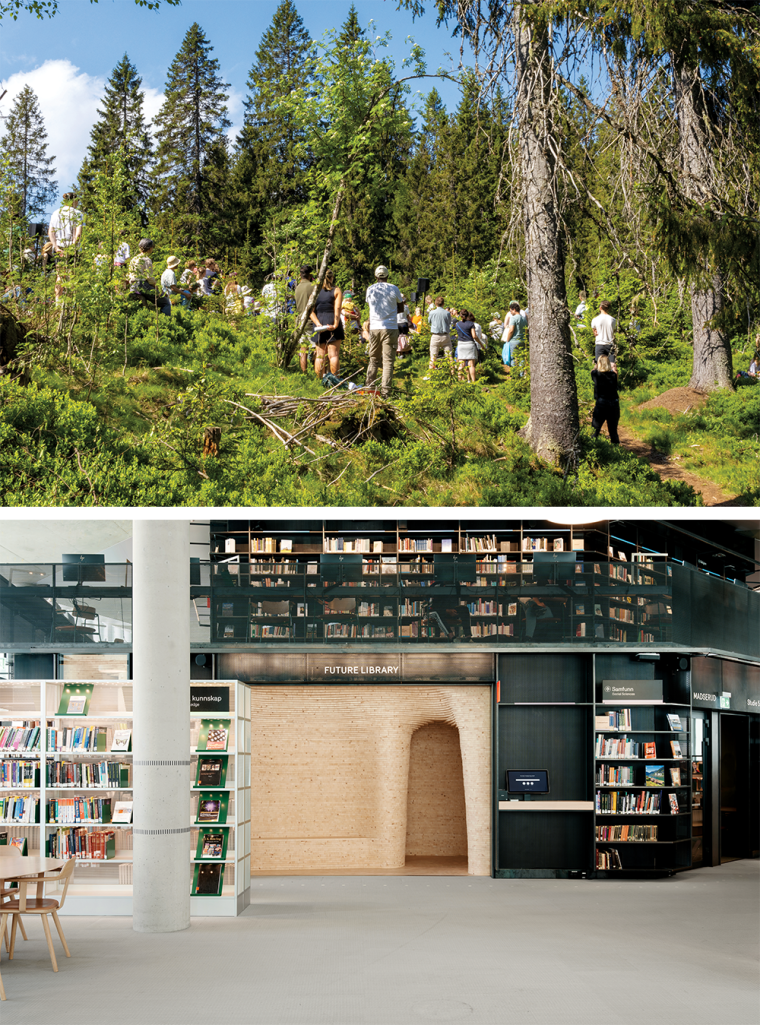

Top: A crowd assembles for Valeria Luiselli’s handover ceremony in a spruce forest in Oslo in 2024. Luiselli was the tenth author to contribute to the Future Library. Bottom: The Silent Room, situated on the top floor of a public library in Oslo, contains one hundred drawers built into the walls where the authors’ manuscripts are preserved. (Credit: Vilma Taubo, Einar Aslaksen)

The spruces were planted in 2014 as part of the Future Library, a one-hundred-year art project by Scottish artist Katie Paterson. Every year a different author is invited to write a new piece that will be held, secret and unread, until 2114, when all the works will be published using paper made from the spruces’ then-mature wood. The inspiration for the piece arrived for Paterson during a train journey when she had a sudden vision of trees whose rings held words. Though the particulars evolved, the original idea remains, she says, of “trees being books, books being trees, and libraries being forests in the making.”

At the first handover ceremony, during which inaugural contributor Margaret Atwood presented her manuscript among the saplings, the trees were so small that staff decorated them with red ribbons to prevent attendees from trampling them. Now the trees are gawky adolescents, their ribbons decorative rather than practical—a testament to the project’s first decade and time’s insistent trudge. The Future Library continues to inspire imagination and instill new ideas in writers and readers alike through its abiding belief in a future full of stories.

Some sixteen thousand pieces of wood from trees cut down to make space for the spruce saplings were incorporated into the Silent Room, a chapel-like venue that opened in 2022 in a public library in Oslo, where all one hundred texts will be entombed until 2114. The chamber was designed with longevity in mind, using ultra-simple construction methods and specialty lighting. It is also beautiful: warm, wooden, and womblike, big enough for a few people at a time to sit in shoeless contemplation, just a few feet from manuscripts they will never read.

The chair of the Future Library Trust, Anne Beate Hovind, helped spearhead construction of the Silent Room; she is also the original commissioner of the work, part of a public art initiative connected to the redevelopment of Oslo’s waterfront. Over the years, she has also identified land for the saplings, overseen their planting, and negotiated a century-long contract that ensures their protection and maintenance by municipal foresters. Thus far ten authors from across the globe, including 2024 Nobel Prize winner Han Kang and Zimbabwean novelist Tsitsi Dangarembga, have deposited manuscripts there. (This year’s contributor, Tommy Orange, will hand over his manuscript in the summer.) They are invited to do so and paid a flat fee, by a surprisingly small team—including Hovind, Paterson, and the leaders of the city library and three publishing houses. The goal is for the collection of works “to be read as a global project,” Hovind says, so the group works together to generate a long list of candidates, incorporating nominations from interested embassies and past contributors, before coming to a consensus.

For the Icelandic writer Sjòn, who goes by a mononym, the project represents an exquisite metaphor for literature itself—a tradition that binds human beings together across generations. Through literature, he says, “I can have a conversation with someone who has left traces of [themself] three thousand years ago in a poem,” and participating would allow him to engage similarly with future readers.

Still, he found deciding what to write almost impossibly daunting, as did 2022 contributor Judith Schalansky. She obsessed over her contribution, reading the requirements over and over—she even considered submitting hardcore textual pornography as a commentary on the immense possibilities of a no-questions-asked publishing guarantee. In the end, both she and Sjòn took inspiration from the way today’s century-old texts illuminate their era to shape their contributions.

Both authors also found the secrecy to be a particular challenge. “I realized how much I write for the present,” Schalansky says. Meanwhile Sjòn, who had previously believed he wrote solely for himself, was surprised to find the process deeply lonely without the possibility of feedback.

The project’s annual handover ceremonies have become important waypoints marking the library’s age and progress. Each ritual is unique and open to the public: Ocean Vuong’s featured chants by Buddhist monks; Karl Ove Knausgård’s, a recitation of an ancient Norwegian poem; Sjòn’s, a song performed by his wife, with harp accompaniment.

Afterward, walking among the spruces, Sjòn was keenly aware that he was following the same path, quite literally, as writers before and after him, shared custodians of a sacred, multi-millennial storytelling tradition. Much of the work of the Future Library engenders this kind of deep mutual trust across time, Hovind says, in the trustees who will come after her; in the longevity of the rituals and mechanisms she and Paterson have spent years putting into place; in the human beings who will receive the books in an unknown world. That means fighting the impulse to solve or predict every technological, societal, or ecological eventuality of the next ninety years. Paterson adds: “I think taking it decade by decade is all we can do.”

It will be up to future trustees to figure out how to make spruce trees into paper or where to print the books. And, Hovind wonders, what if the forest around the library saplings is developed? How will the trees fare as temperatures rise?

At the project’s start the climate crisis was looming, Paterson says, but its rapid intensification has changed how people engage with the library today. In 2014, she and Hovind were frequently asked if they thought there would still be books in one hundred years. Now in contrast, she observes, “It has turned to, ‘Will there be people?’” In the face of the doom and doubt of the contemporary zeitgeist, the project has become a source of optimism that contributing authors cite year after year, moved by its certainty that we can still build a literary future.

This hope is not without complexity—after all, the Silent Room was built with trees sacrificed to the cause, and more will fall in ninety years—but it sends a powerful message nonetheless. The Future Library prompts its audience to consider the “good ancestor perspective, how to take future generations into consideration now,” Hovind says, while insisting on the immortality and influence of storytelling: “If you can imagine futures, with strong narratives, you can also create them.”

Alissa Greenberg is an independent journalist based in Boston and Berkeley, California, who reports at the intersection of science, history, and culture. Her work has appeared in the Atlantic, the San Francisco Chronicle, the Washington Post, the New Yorker, and elsewhere.

Thumbnail credit: Kristin von Hirsch