Many writers have wondered, when embarking on a new project, what might happen should Fate intervene and prevent them from finishing. This isn’t the most pleasant thought, however, and for this reason some of us have yet to make provisions for what should be done with our work after we die. Perhaps this is because we the living tend to assume there will always be more time.

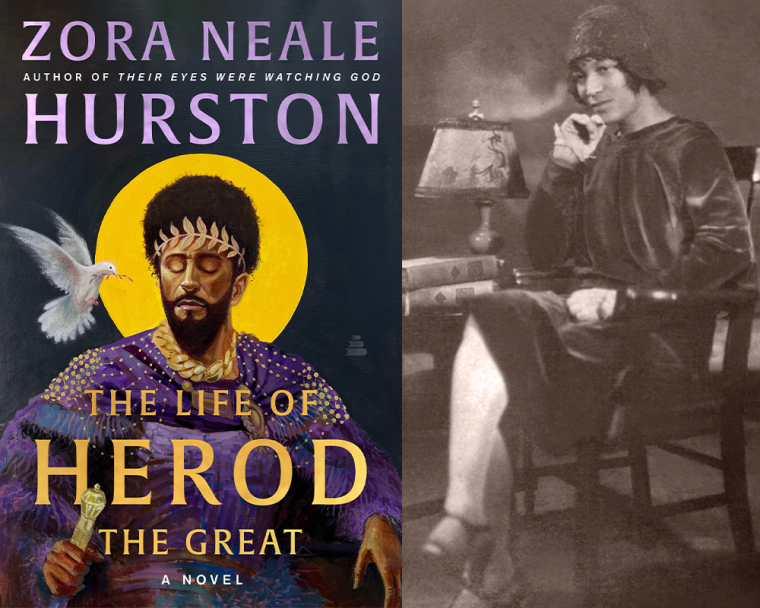

The Life of Herod the Great will be published by Amistad in January. (Credit: Barbara Hurston Lewis, Faye Hurston, and Lois Gaston)

The writer, anthropologist, and folklorist Zora Neale Hurston was likely no different. Hurston spent nearly fifteen years conducting research for The Life of Herod the Great, which will be published by Amistad in January. In one letter to an editor, Hurston called the novel her “great obsession” and described the work she was undertaking to translate conflicting historical accounts into a fictional narrative “the most formative period of [her] whole life.” If not for her failing health, surely she intended to continue the painstaking process many writers know well: writing and revising, then submitting and revising anew if the book failed to find a home. She had queried editors (and unfortunately, received their rejections) up until a year before her death in 1960. Versions of the manuscript were found among her belongings, eventually making their way into the University of Florida archives and the hands of Deborah G. Plant, the editor of The Life of Herod the Great as well as Hurston’s Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” (Amistad, 2018).

What might Hurston have thought about readers receiving this new novel in its current form? And, more important, what does The Life of Herod the Great tell us about the writer who authored it and her vision for her life’s work?

The novel, which will be published on Hurston’s 134th birthday, is a fictionalized biography of Herod, a Rome-appointed ruler of Judea during the first century BCE. In a preface that will be published with the book, Hurston writes that she chose his story because “the West, whose every nation professes Christianity, should be better acquainted with the real, the historical Herod, instead of the deliberately folklore Herod.”

Hurston is right: Herod’s legacy in the modern world is fraught, dominated by claims in the Gospel of Matthew that he personally ordered the deaths of Bethlehemite male children ages two years and younger around the time of the birth of Jesus. However, her research and that of later scholars suggest that Herod’s paranoia about being overthrown by an infant Messiah was unlikely, and among his subjects he was a popular and progressive king (albeit sufficiently brutal for his time and the mores of Roman rule). Yet instead of focusing on Herod’s anti-Christian infamy, Hurston turns to his shrewd manipulation of family, friends, subjects, and foes. She is meticulous in her re-creation of his inner life, describing everything from his private musings about love to the bejeweled embellishments of his tunics. In this melding of fact, fiction, and fable, we see Hurston in her finest form: a well-versed cultural historian who has done her research and grapples with archival inconsistencies, reconstructing a narrative that approaches the truth in a fascinating new way.

And, still, what we have received is not as complete as Hurston might have intended. As an editor’s note explains at the front of the book, the triple asterisks that become increasingly more frequent in later chapters denote missing sections and pages, some of which were likely lost in a fire set by workers clearing Hurston’s belongings from the welfare home where she was living at the time of her death. Other sections might have simply not yet been written. For instance, the final full chapter of the novel reads more like a summary than anything, and the book itself ends with snippets from Hurston’s letters, in which she outlines her intentions for writing Herod’s peaceful death, a marked contrast to historical accounts of his suffering from phthiriasis, a putrefying illness caused by lice. This detail is interesting because, unlike the discrepancies surrounding Herod’s rule and its potential overlap with the life of Jesus, nearly all historical accounts agree that he died a painful death. Hurston’s decision to write Herod’s death this way raises some interesting questions. Is it, in part, due to her lifelong commitment to bucking the status quo and disrupting preconceptions of what it means to be an artist—and a Black one at that? Should we think of the book as “unfinished,” or consider its truncated state emblematic of Hurston’s ever-evolving and still-unfolding legacy?

By all accounts Hurston was a mythic iconoclast. At my alma mater, Fisk University, a small, historically Black college founded in part with help from the American Missionary Association, stories abound about her time on campus in the 1930s. According to lore she raised eyebrows by wearing pants and smoking cigarettes on school grounds, and according to her own letters she once told Fisk’s then-president Thomas Jones that he “ran his school like a Georgia plantation” filled with “good n⸺ s.” She consistently thwarted expectations and ruffled a few feathers in the process. The Life of Herod the Great stands squarely in the ethos of Hurston’s life and work, from her depiction of Their Eyes Were Watching God’s Janie Crawford, who walks away from one marriage and is relieved when the next husband dies of old age (allowing her to meet her true love, Tea Cake Woods), to what is considered the prequel to The Life of Herod the Great, a retelling of the Book of Exodus titled Moses, Man of the Mountain (1939), in which Hurston suggests the titular character was Egyptian—in essence, an African. In these and her other books, Hurston challenges readers to set aside what they have been told to believe—that women must settle for their lovers and their lives, or that our culture’s greatest heroes are white—and asks us to reconsider our received truths. In the case of Herod the Great, she raises questions that were undoubtedly on her mind during the decades she worked on this book, which spanned the wake of the Harlem Renaissance to the cusp of the civil rights movement, one of the most violent eras in American social history. Those questions persist today: Who gets to tell the story of who we were, how we lived, and what we did? And who will be brave enough to refute it if the full story isn’t told the first time? The answers to these questions are as complex as the central figure in Hurston’s new novel and are, in some ways, as incomplete as the text we have now received. But that reality is not a shortcoming. It’s an exhortation to continue this asymptotic work of trying to perfect the art we make about an imperfect world, imperfect people, and our imperfect selves. And to keep at it, whether we are destined to finish the task or not.

Destiny O. Birdsong is the author of the poetry collection Negotiations (Tin House, 2020) and the triptych novel Nobody’s Magic (Grand Central, 2022). She is a contributing editor of Poets & Writers Magazine.