Four years ago American painter Eric Fischl was musing in his studio in Sag Harbor, New York, when his thoughts turned to the unsettled nature of the everyday conversations he’d been having with friends, students, and folks he’d recently met. “It didn’t matter the topic,” Fischl recalls. “What linked them all was this unshakable feeling that everything had become toxic, and because of that feeling the future loomed as a terrifying prospect.” It occurred to him that this apprehensive mood—precipitated in part by the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, an increasingly polarized political atmosphere, and the faltering economy—was shared by many in the country, and that the artistic community was well equipped to instigate a dialogue shift. “It is not a reflex for Americans to turn to their artists to ask for help, to ask artists to give language, images, form to these persistent terrors. But this is what art does best. It connects us,” Fischl says. “I thought, let’s try to shift the way we’ve been relating to one another. Let’s treat one another to a conversation less vitriolic, polemical, and dogmatic. Let’s be more creative in our approach and use the artistic talent pool to lead the way.”

Fischl’s idea has taken form as the national art project America: Now and Here, a preview of which is currently on view in Detroit until July 24. Transported by custom-designed trailer trucks that act as galleries, the modern-day traveling show brings the work of some of America’s leading poets, musicians, visual artists, playwrights, and filmmakers to audiences in small towns and big cities, at community colleges and military bases, and invites local artists to add to the exhibition.

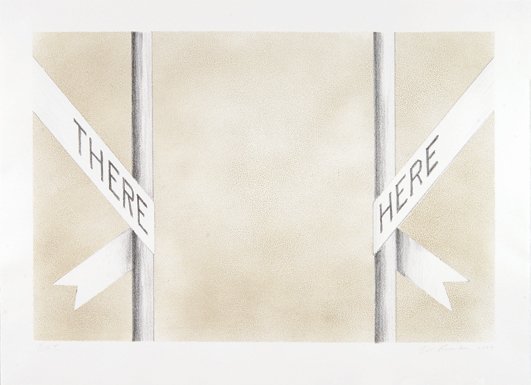

“This is not about art,” says Fischl. “This is about using art to bring us into a different kind of relationship with one another. So I asked my artist friends to help out by creating works about what they would like us to focus on in America now.” Among those involved are painter Jasper Johns, composer Philip Glass, playwright Edward Albee, and performance artist Laurie Anderson, as well as fifty-four contemporary poets who contributed to a collaborative long poem edited by Bob Holman and Carol Muske-Dukes. “Crossing State Lines: An American Renga,” which was published as a book by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in April, appears in America: Now and Here as lines of text projected on walls and accompanied by a film of the writers in performance.

Fischl approached Holman and Muske-Dukes three years ago knowing that they come from different poetic aesthetics and would curate a work generated by a diverse list of contributors. Holman, who is known for his spoken-word and performance-oriented focus, and Muske-Dukes, who is traditionally a “page” poet, solicited about seventy poets, about three-quarters of whom ended up participating. After many discussions, Holman and Muske-Dukes arrived at a poetic form that could unite a diverse roster of poets. “I thought of the renga (which means ‘linked poem’), a nine-hundred-year-old Japanese form, because a renga is a conversation and it seemed the right time for America to hear its poets converse,” writes Muske-Dukes in the introduction to Crossing State Lines.

A renga begins with a three-line stanza of seventeen syllables. The poet who starts then passes it to another poet, who writes a couplet of seven-syllable lines. The creation of another three-line stanza followed by a couplet is repeated and the renga continues, passed from poet to poet until it is finished. “Crossing State Lines” deviates slightly from the traditional form, however; each poet was asked to write ten lines that would then be passed to the next poet in the series.

Former poet laureate Robert Pinsky was first to carry the torch, and commenced the renga with the lines, “Beginning of October, maples / kindle in the East.” Fifty-three stanzas later another former poet laureate, Robert Hass, finished the poem on the West Coast, imagining hikers who “Unpack their lunches and stare at the Pacific.” In between Pinsky and Hass, poets such as Rita Dove, Mark Doty, Marie Howe, Adrienne Rich, and C. D. Wright joined the conversation.

“There is plenty of news,” Holman writes of the poem’s themes in the book’s introduction. “We get a new president (via Susan Wheeler, also remarked on by Howe and C. K. Williams), who is gazelle-like when inaugurated (Anne Waldman), and prayed for (Edward Sanders). Special days pass by: Halloween (Jane Hirshfield), Day of the Dead (Joy Harjo), winter solstice (Doty), and New Year’s (David Lehman).” Many of the poets write about foreclosures, job losses, and the country’s two ongoing wars. Toward the end of the renga are ten lines from Edward Ledford, a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army, who reflects on a wartime suicide in Afghanistan: “The / soldier-philosopher turns the gun on himself to salvage some meaning.” Despite touching on topics that have darkened the national conversation in the past few years, Holman says, “The poem moves, works, and, I hope, fulfills Fischl’s vision.”

In addition to the traveling show, America: Now and Here showcases collaborative works by poets living in the exhibition’s host cities. In Kansas City, where the preview launched in May, thirty poets created their own renga, which was displayed adjacent to “Crossing State Lines.” The poem turned out to be “a love song of sorts for the city,” says Fischl. “It’s not a sweet love song, but it is a song of committed love, an ‘I’m not going away’ kind of love.”

The preview of America: Now and Here continues this October in Chicago before the project fully launches next fall, with an initial two-year tour. For more information on where to catch the show or how to get involved, visit americanowand here.org.

Alex Dimitrov is the founder of Wilde Boys, a queer poetry salon in New York City. He is also coordinator of the Poets Forum and awards at the Academy of American Poets.