Like anyone, I'm a sucker for a good underdog story. In a world where the bad guys always seem to come out on top, give me Gary Cooper in High Noon or Fred Exley in A Fan's Notes or even, I'm sorry to admit, Meg Ryan in You've Got Mail. Who doesn't appreciate a life-affirming tale of triumph and redemption in the face of adversity?

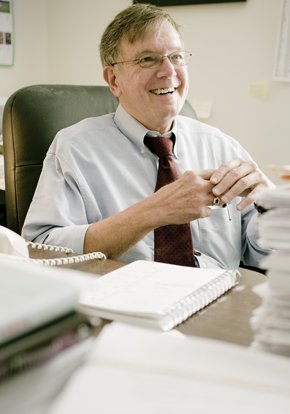

Not long ago, I went down to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, to seek out the protagonist of one such story: Chuck Adams of Algonquin Books. A native of Virginia who was educated at Duke, Adams moved to New York City in 1967 and found an entry-level job at Holt, Rinehart and Winston. He moved on to Macmillan, then Dell, where he built a reputation as a brilliant line editor, and was eventually recruited by Simon & Schuster to work alongside celebrated editor Michael Korda. In the years that followed, Adams edited and acquired an extraordinary range of best-selling and award-winning books by authors such as Sandra Brown, James Lee Burke, Susan Cheever, Mary Higgins Clark, Kinky Friedman, Ellen Gilchrist, Joseph Heller, Ronald Reagan, and Elizabeth Taylor. In all, nearly one hundred of the books he's edited have gone on to become best-sellers.

In the winter of 2004, however, like many editors of a certain age (and pay grade), Adams was rewarded for his years of service with a pink slip. The news hit him hard. Believing that his career was essentially over, he moved back to North Carolina, where he had gone to school and still owned a house. Not long afterward he got a call from a literary agent and friend who told him that Algonquin Books, the small literary publisher in Chapel Hill, was looking for an editor. He landed the job and soon acquired a book by a little-known novelist named Sara Gruen that her previous publisher had rejected. Anyone who's walked into a bookstore in the past year probably knows the rest: Water for Elephants has gone on to become a publishing phenomenon, spending a year and counting on the New York Times best-seller list with sales of more than two million copies to date.

But the redemption story is only part of why I wanted to talk with Adams. I heard a rumor that he was a straight shooter, and I had a hunch that his experience at publishing houses both large and small, and his extensive background with commercial authors, would yield some unique insights that writers of all stripes might find useful. In our wide-ranging conversation, Adams spoke with rare candor about everything from how to craft a compelling narrative to what the best agents do for their clients to the intricacies of working with an editor. We talked in his office, one wall of which is dominated by a thank-you gift from Gruen: a large, wildly colorful abstract painting that was made by—you guessed it—an elephant.

I've read conflicting things about your background. Where are you from?

I was born in Virginia, but just over the border. I think it was Publishers Weekly that said I was from North Carolina. I went to school at Duke—I did undergrad and then law school and spent seven years here. So coming back to Chapel Hill and Durham is coming home for me. I studied English as an undergrad and then went to law school because my father wanted me to go to law school, and Vietnam was happening and I didn't want to go there. The irony is that when I finally finished law school and had to go for my physical I didn't pass it because of a hereditary skin disorder—psoriasis, the heartbreak of psoriasis—and I had thrown away three years for nothing, I thought at the time, because I knew I didn't want to be a lawyer. But I did know that I wanted to go to New York. So I took a job as a lawyer with a bank in New York just to get there. I kept not taking the bar, and they finally said, "You don't really want to practice, do you?" I said, "No, I really don't." By then I had become acclimated to the city and basically just took the law degree off my resumé and went out and found a job at Holt. It was an entry-level job in production. I spent about three or four years there and worked my way up pretty quickly. Then I went to Macmillan and was hired as a managing editor. I think I was hired because they had been fighting for so long over who to hire that they basically said, "We're hiring the next person who walks through the door." I was the next person who walked through the door. I had to learn the job, and I was terrible at it.

How did you make the transition to becoming an acquisitions editor?

I made a couple other moves and eventually wound up at Dell. By then I knew what I was doing. I was good. Dell was very much into movie tie-ins. As managing editor, I oversaw a lot of stuff, but there was an editor who did the acquiring of all the tie-ins. At some point they decided they weren't going to do that anymore. They fired that editor and said, "Chuck, you take over the tie-ins. It's basically just getting the artwork from the movie companies anyway." I said, "But if something comes my way, can I acquire it?" They said, "Sure." The first think I bought was a tie-in to a miniseries called The Blue and the Gray. It was a complicated situation, and the author and I didn't get along. He had come up with the idea for the miniseries and somebody else had written the screenplay. But he retained the rights to novelize the thing. So he wrote the novel but he didn't have the approval of the edit—the producer had that. I read the novel and called the producer and said, "This is terrible. I can't accept it like this, or, if I do, it has to be rewritten, and I will rewrite it because I want to make it a success." He said, "Do whatever you want." So I completely rewrote it. The author was really upset. You know, I had destroyed his career and everything. We published it that way, as a paperback original, and it went on the New York Times best-seller list. We sold it to something like fifty foreign countries. It was a huge success. We made a fortune off it. So I'd taken my first book and turned it into a big success, and after that they encouraged me to acquire more. Eventually, Susan Moldow made me just an editor. But my reputation thereafter was based primarily not on my successes but on the books I didn't buy.

What do you mean by that?

I got a reputation for wanting to buy certain tie-ins and being told, "That's a terrible idea." For example, I was desperate to buy the tie-in to Cocoon. When I told them the plot, they practically laughed me out of the editorial meeting. Another was V. Another was The Last Starfighter. They all went on to be huge best-sellers. I was a big I-told-you-so person. When it came my turn in the editorial meetings, and they'd ask if I had anything that week, I would stand up and read the New York Times best-seller list to them. So I had this reputation for knowing what I was doing but never getting to do it. Eventually it became apparent to them that I did have talent as an editor. I'm good at it. I had done it a lot more than I had realized. I could type, which was rare back then before computers. I'd taken a typing class in high school, and in college I was the only guy on my floor who could type. I'd be typing guys' papers for them all the time, and I'd say, "This isn't very good. Do you mind if I change a few things?" They'd say, "Sure, go ahead. I don't know what I'm doing." So I'd rewrite their papers, and sure enough they would get much better grades. So I knew a long time ago that I actually did know how to write.

So you basically taught yourself how to edit?

Yes. Completely. Nobody mentored me, nothing like that. I got a reputation for being a really strong line editor, and eventually I heard that Michael Korda was looking for somebody to come work with him. That's how I got hired at Simon & Schuster.

Did you know Michael before you went to work with him?

No, I'd never met him. What happened is that a headhunter, Bert Davis, called me and said, "I've got a job for you. You've just got to promise me that you aren't an alcoholic or a drug addict." I said, "Okay, I'm not." He said, "Don't ask." It turned out they had hired somebody for the job and it became clear very quickly that he had a real problem—I don't know if it was drugs or alcohol or what—and it didn't work out. I guess they figured that was the one question they forgot to ask. So I went over and had an interview with HR. I was really pissed about that. I thought, "They called me. I'm not applying for this job, am I? Why am I having to go to human resources?" I remember the question that cinched the job for me. The HR woman said, "Rate yourself on a scale of one to ten." I said, "Ten!" She said, "Good, that's good." I realized that was what they wanted—belief in yourself and arrogance. Because it was more in my nature to say, "Oh, you know, like a seven and a half." I think I was just irritated with her.

When I met Michael I immediately loved him, of course. At one point in the interview he said, "What do you think is your greatest talent?" I said, "I grovel well." That may be the thing I said that got me the job. I didn't mention this earlier, but one of the other things that happened at Dell was that I started being assigned to a lot of problem authors. I've always been a placater or a mediator—my shrink tells me it's because I grew up in an abusive environment with a lot of drunks, not my parents necessarily, but I was around a lot of that—and it became clear to the people at Dell that I could get along with anyone. They would just throw people at me and say, "Let Chuck handle this one." So when I told Michael I groveled well, I think he liked that. I was basically hired the day I met him.

Tell me how your relationship developed.

On a personal level, we liked each other and still do. We just became friends, and we still talk on a regular basis. On a professional level, Michael is probably the most talented editor I have ever known. There were sessions with him and writers—I'm thinking of times when a writer was having trouble with an idea—and on a day when Michael completely focused, he was brilliant beyond belief. I remember one day in particular with an author who was stymied on this one plot problem. I had thought about it and hadn't come up with anything either. We went in and sat down with Michael and he just started to talk. He talked for about half an hour—talking through the story—and he resolved the problem and went on from there. It was a hair-raising experience. I was so moved by it. It was so exciting. I thought, "This man is brilliant."

Michael could do anything—I'm sure he's a great line editor—but he was more than happy to let me do the line editing. So, for the most part, I did the heavy line work on books and he did the more developmental side. That's especially true with Mary Higgins Clark. Mary is a dream to work with, one of the nicest people in the world, and I think an extremely talented writer, because she's a great storyteller, and I put storytelling ability above fine writing. When she was starting on a book, she and Michael and I would meet, usually for dinner. She would say what the idea was, and then Michael would spin this whole thing. She'd take that and run with it and do her own thing, but Michael helped her come up with the direction. Then I would go in and line edit the book.

Michael and I had a great working relationship, and we had that relationship with most of the authors we shared. Every now and then there would be somebody who I didn't work with. For example, Michael took on Philip Roth, who I got to know ever so slightly, but Philip Roth is Philip Roth and you basically leave it alone. I didn't work with Larry McMurtry at all. Larry is not the easiest person in the world to get along with, and he and Michael had a great relationship, so I was happy to stay out of that.

How did it work, technically? Would you both acquire your own books and then acquire some of them together?

I acquired books on my own, but usually, if an agent sent me something that I really liked, I would go to Michael and say, "I really like this and I want to try and buy it." And 90 percent of the time Michael would say, "I like it, too. Let's buy it together." So that's what we would do, and he would do the same thing with me. Every now and then he would get something—he was in the RAF and knew about planes—where there was no reason to involve me. We didn't do every book together, but we did the majority of them together. Usually agents would send the big authors to him. But Sandra Brown and James Lee Burke were submitted to me.

When you look back, what did those years working with Michael teach you?

Well, I learned an awful lot about the business from Michael, of course, because Michael is incredibly savvy. I also learned the limits of ego.

What does that mean?

I believe it's never, never, never about the editor. That was the only thing with Michael that I sometimes disagreed about. The most important thing is to have a really strong relationship with the writer and have them be confident in you and the house. As the editor, I'm not important in that equation. I genuinely believe that. I mean, I have an ego, but it's not important. Michael would occasionally let his ego get in the way of things. There was one celebrity—we did a lot of celebrity books—and they had a fight, the likes of which.... I had seen it coming. I knew it was going to happen. And it ended up that I was the only one she would talk to. His ego could occasionally get in the way. I have come close to losing my temper with authors, but I've only actually done it twice, once here and once, famously, at Dell.

Comments

eforest replied on Permalink

Capturing The Voice

Tree replied on Permalink

James River Writers Conference

DC Spencer replied on Permalink

Chuck Adams interview

wordofmouthco replied on Permalink

Chuck Adams Interview

melissacwalker replied on Permalink

Fantastic!