What makes a literary agent great? It is not necessarily editorial acumen, negotiation skill, or relationships with powerful editors, but rather the strength of an agent’s conviction about the writers and work that agent represents. Of course, being shrewd, tough, and connected doesn’t hurt—but the most important thing any of us in the publishing world can do is believe passionately in authors and their ability to communicate something real.

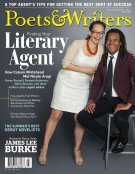

But where does that conviction come from? That is what I sought to discover by talking with PJ Mark, an agent whose clients are among the freshest voices in American writing, but whose path into the agenting business was anything but direct.

Mark made his way from Scottsdale, Arizona, where he played in a punk band, to New York City in 1990, where he founded Feed, an alternative literary journal, with his student loans. Soon thereafter he began to evaluate projects for Ballantine Books, and through a chance meeting while he waited tables at a macrobiotic restaurant, he became a book scout for foreign publishers. He later worked as a journalist covering the publishing industry, and since 2002 has been a literary agent, first at International Management Group (IMG), then Collins McCormick, McCormick & Williams, and now Janklow & Nesbit Associates, where he moved in 2010.

Mark’s list of authors includes five writers who have received 5 Under 35 honors from the National Book Foundation—Samantha Hunt, Grace Krilanovich, Dinaw Mengestu, Stuart Nadler, and Josh Weil—as well as many other notable writers, including Rachel Aviv, Rosecrans Baldwin, Jim Gavin, Shelley Jackson, Wayne Koestenbaum, Sarah Manguso, Maggie Nelson, Ed Park, and Craig Thompson.

Let’s begin at the beginning.

I grew up in Arizona in the seventies and eighties, in what was then a small suburb called Scottsdale. I was the youngest of seven kids.

What was your first experience with reading?

I don’t have those memories of sitting in the back of the car reading or being in a library and borrowing books. I really struggled as a young person. I wasn’t a reader. I was a gay, poor, punk-rock kid in Scottsdale, and I fell into music instead.

That changed in high school, when I was the lead singer of a punk band. Through lyrics and music I began to understand the power of expression through writing. There was an album of spoken-word poetry released by Exene Cervenka from the punk band X and an African American poet named Wanda Coleman—literally a pressed vinyl album—called Twin Sisters that I listened to on a loop. They talked about cultural issues and outsider status, and that sort of alternative writing led me to the kind of people you would expect: Kathy Acker and William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg. Those were the writers I fell into reading and really loved.

It took me a while to develop the skill to sit down with a book and to allow it to take me on a journey. With the vocabulary and reading issues I had when I was younger, I didn’t have the capacity to fully comprehend what I was reading, so I would just shut down.

What else was going on in your life? Were you acting out or involved in drugs?

Both of those things. I had a nihilistic view, and took a lot of risks and engaged in dangerous behavior. Then two things happened. The first thing was writing: learning to express myself creatively, and finding other creative people to engage with. That directed my energy toward something productive. The second thing was that my twenty-eight-year-old brother killed himself when I was eighteen. I saw that I was pointed toward a really self-destructive path. I saw that I had to get the fuck out of Arizona and change my life. I had to turn everything around.

I got into Arizona State University, but I was determined to get to New York, because it was the furthest place from where I was. I knew New York would allow the kind of creative exploration I was interested in. I wanted to write fiction.

Wow.

My mother was determined for us to have a different future than what she came from. We were first-generation college graduates, my brothers and sisters and I. She expected us to do something with our lives. I was good at working through the requirements of what was expected of me, but I floundered with traction and had to find my own way. That brought me on a path to publishing and directed me to make the decisions that I’ve made throughout my career.

How did you get to New York?

I applied myself and transferred to NYU as a junior in 1990. I was putting myself through school by working full-time, five nights a week, at Tower Records. It was hard to work until 2 AM, close up, and get to class at 8:30. I dropped out and decided that the best way to get what I wanted, which was then to be in publishing, was to delay my studies for a year and finish up at Hunter College. Hunter was a community of other students who were also putting themselves through school. There was no campus to lounge around in. You arrived and you got down to business and you left and you had the rest of your life, and that was very meaningful.

How old were you then?

I was twenty when I came to New York in 1990. And then in 1991, when I was still in school, I used my student loans to start a literary magazine that lasted a few issues.

Tell me about that magazine.

It was called Feed. The parenthetical was “Eat your critique,” which was just a preemptive fuck-you to anybody who had anything to say about it.

The idea was to encompass marginalized voices. There were some very cool queer-theory things happening at the time, and a lot of gay and ethnic and marginalized writers were finding traction. Cool stuff was happening at the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church. The Portable Lower East Side journal was being published. And Ira Silverberg had released High Risk: An Anthology of Forbidden Writings, which was mind-blowing for me.

At one point, I went to a poetry reading by David Trinidad at the New York Public Library. It was pouring rain, and Ira was there—he and David were partners at the time—and there was a writer, Rachel Zucker, who wound up being a student of Wayne Koestenbaum. David read to the three of us and then we had this four-person conversation. I told them that I was working on this literary journal, and Ira, in his infinite generosity, said, “You should come to my office and look at the CLMP,” which was a bound book of information about distributors and printers. Then he said, “If it’s useful, I can introduce you to people.” Ira was one of the first people I met in publishing and he really set me on a path. I’m very grateful for that.

Were you still playing in a band?

I had aspirations to be Ian Curtis, right? But I didn’t have a very good voice, and depressive music only goes so far. There was just no time for it, and there was no money in it.

I once auditioned for a band and lost my voice the next day. I thought it was a sign from the universe that it was the wrong thing to be doing. I was here to be in school, to be a writer, to be in publishing. So I redirected the energy towards curating a creative community of writers and friends.

I arrived as a young gay man in New York in the midst of the second half of the AIDS crisis. It is a very scary thing to suddenly have friends who were dying, and not know how to navigate a sexual world when you’re coming of age. But there were writers like Dale Peck, who was writing Martin and John. And a little bit later, Scott Heim was writing about this new queer coming-of-age.

After the High Risk anthology, Ira published a list of “High Risk” books and I bought and read every single one of those. They were voices of a very specific New York time, and they probably feel very dated now, but they were about rock and roll culture, drug culture, gay culture. Gary Indiana and David Trinidad and Dennis Cooper and June Jordan and Lynne Tillman—these were important voices at a very important moment for me. They crystallized what writing could be, and what books could be. They were seminal in the way that I viewed what was possible in fiction and nonfiction, and how one could express oneself.

These books became a part of you.

They did. Those writers became the rock stars for me. Those writers were marginalized, and that made me more interested in them. I felt that they were clearly saying something that needed to be said but weren’t given a larger platform to say it.

Tell me about the literary scene.

The community of reading was different in the 1990s. When something was reviewed in the New York Times, a new writer debuted, or someone was on the cover of the Book Review, it became part of the cultural conversation. It was your responsibility to read that book and to be engaged in that conversation. That was what you did. You read the New Yorker for their listing of readings, and looked at the Village Voice for what was upcoming. You went to the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s and you saw those writers read and you were part of it in a way that just feels different now.

Alternative culture was different, too, because it wasn’t commoditized and it wasn’t gentrified. The East Village was rough. I was on Thirteenth Street between First and Second Avenues. Between Second and Third was a crackhouse and between First and A there were heroin dealers. Tompkins Square Park had been shut down. You also didn’t go much west of Eighth Avenue—that was also sort of scary. New York was grittier.

I browsed bookstores like I would browse indie record shops. I would browse through covers and see that an album was put out by 4AD, and buy it, or that it was from IRS Records, and think it would be amazing. I would see a book on the shelf from Grove, or Knopf, or FSG, and think that it must be important.

When did you realize that you could get a job in publishing and help bring those books into print?

In my senior year of college at Hunter, Ira introduced me to somebody who knew the assistant to Clare Ferraro, who was then at Ballantine Books. This was back when one publisher would publish a hardcover, and other publishers would buy the paperback rights. They would get these hardcovers in and evaluate whether they were viable as paperbacks. But there was such a volume that they needed readers.

I was paid thirty-five dollars per book. It would take me eight hours to read, and four hours to write a report on it. But I learned how to discuss literature in shorthand, and to identify what was viable and what was relevant. That was my first inkling that publishing is a business, and that there are decisions that go beyond art and have to integrate commerce. Sometimes it’s just art, and sometimes it’s just commerce, and that’s okay. But the beauty is in the intersection of both.

At that point, I was also waiting tables at a macrobiotic restaurant, so you can imagine how much money I was making. [Laughs.] A young woman kept coming in, and she would read galleys and the New York Times Book Review before it came out, and I thought that was astonishing. We would talk, and she eventually said, “I work at a company around the corner and we’re looking for an assistant. You should come in for an interview.”

That was Mary Anne Thompson’s scouting office. I was able to arrive at Mary Anne’s office with the reports I had written for Ballantine and a literary journal of writers I had scouted and published and say, “I’m sort of doing what you’re asking right now: I’m looking at contemporary writers and evaluating whether they can be published, and I’m also engaged in this conversation with a mainstream house.” Mary Anne hired me immediately.

Comments

redbelle3 replied on Permalink

RJ Mark

It felt a little surreal when PJ Mark began to recount the people at ICM: Mark McCormark, David McCormick, Nina Collins, and Collins McCormick.

andersonclingem... replied on Permalink

A new home for defunct journals

Mike Joyce, it's not an "old cliche" (...maybe only a hundred people heard the album, but all of those people went out and formed a band). It's a quote about the first Velvet Underground album, with Lou Reed, Nico, et al. And it's "Maybe only a hundred people bought the album...etc).

Thank you.

Anderson Clingempeel