Tell me about a clever online thing that you think has worked.

We're doing a ton of smart online outreach for NurtureShock by Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman, thanks largely to Po and Ashley. They have given us extensive lists of bloggers who have written about parenting or science or the science of parenting. We've approached people to have them speak at parenting conferences and we've got something like thirty dates lined up. We're doing a kind of open source book club where people will be able to comment on chapters publicly. We're doing very targeted online advertising on parenting blogs. So it's a multipronged marketing approach that really speaks directly to the people who we think are going to be the first buyers of the book: highly engaged parents.

Another example involves a book we've got coming out right now called The Liar in Your Life. Rather than putting blurbs on the back cover, we solicited the lies that people tell most frequently and used those in place of blurbs. Then we hired a polling firm to poll the lies to determine which ones are the most common. We're going to release that information online and we think it might generate some attention. So that's our one out-of-the-box idea.

The Hitchens example really is the best. But again, that's about a really creative director of publicity. Cary Goldstein had this idea that Christopher Hitchens should debate Al Sharpton at the New York Public Library. And I have to tell you, when Cary told me he wanted to do this, I thought he was nuts. I mean, Al Sharpton? Who would take him seriously? Well, they had the debate, and Al Sharpton stepped right into a big morass when he brought up Mitt Romney's Mormon beliefs. That event got picked up on cable news and was all over TV for two full days. That's all because of a really good publicity director.

One way of looking at what you're trying to do with Twelve is that you're trying to get away from disposable books, which you've written about and called a syndrome in the Washington Post. You acknowledged that there's nothing new about the syndrome and that it's driven by the need for growth in a business that is essentially flat. But what is at the heart of the syndrome, in your opinion? What is the fundamental reason for it?

First of all, there are many ways to publish good books, and I don't believe that our way is the only way. I've thought about this a lot and I've said this in every interview, but it hasn't gotten picked up. I think that you can have a backlist model or a frontlist model. The major publishing companies have a legitimate reason for publishing as much as they're publishing. If you're trying to accumulate the biggest and best backlist, it makes sense to put more out there, and you can even make an argument that letting the market decide what sticks is viable and actually makes more sense in the end. There are publishers who are activists—who want to make their work known—but there are also publishers who want to publish a broad range of books, let the public decide what they want, and then give the public more of that. I think that's a legitimate business decision, and it can work. It can give you the capital to do things on a big scale and to market books, when you want to, very aggressively.

My criticism of the publishing industry and the major publishers is not specific to companies. I've seen what a great publishing company can do for worthy books. I mean, Random House put Seabiscuit and Shadow Divers and The Orchid Thief on the map, and it wouldn't have been able to do that if it didn't have real leverage in the marketplace—if it didn't have the marketing prowess and marketing resources to do that. So I think it's completely legitimate that certain publishers would seek hegemony through volume. I really believe that.

That sounds like a hedge to me. In your heart of hearts don't you have to believe that the way you're doing it is the best way?

Look, it's not for me, at this point in my career.

Why?

Because I think that there are enough really good authors who want focus and attention and who want it promised and guaranteed. And that's harder to do at a big company.

You honestly don't believe that what you're doing is the best way?

I think it's the best way for me in the year 2009. I've really thought about this a lot. And I've written this before: I don't think that people who live in glass publishing houses should throw stones. I don't think it's right for me to get up on my soapbox and say that my way is the best way. What I do think is that the Twelve model makes a great deal of sense for unknown authors or authors who want to break out. I think that's true. I think that this is the best way to publish a midlist author or an author who's on the way up.

Let me put it another way: I think it would behoove the major publishing houses to publish fewer books with more focus. I think that everybody would benefit from that. What I don't know is whether the companies can meet their targets doing it. I'd have to be a CFO to know that, and it would be arrogant of me to say that a major publisher can get by without disposable books. I don't know the answer to that. What I know is that I'm working for a company that publishes a lot less than the other major publishers with a more concentrated marketing approach and seems to be making a lot of money doing it. One of the reasons I came to this company was because it was in the DNA of the company to do fewer books with more marketing force. That was what the Time Warner Book Group had always been about, that's what Hachette is about, and that's what Twelve is about. I wanted to be here for that reason.

When I was at Random House, I felt like I was missing out on something because I thought that Larry Kirshbaum and Jamie Raab and Maureen Egan and Michael Pietsch were publishing books in a really smart, aggressive way. I saw what they did for writers like David Sedaris and Malcolm Gladwell and David Baldacci and Nicholas Sparks, and I really respected that. I thought, "They've got cojones. They're putting their full force behind these books. I want to be a part of that."

I saw this remarkable statistic on your website that you've published twenty-five books so far and thirteen have been New York Times best-sellers. People in the industry know that having a book hit the list isn't necessarily an indicator of profitability. Of the books you've published, how many have made money?

To be honest, I haven't actually counted them one by one. I can't give you that off the top of my head.

But what's your sense?

I know that the imprint is profitable.

You're in the black?

Yeah, I know that. And off the top of my head I would say that roughly half of the books have been profitable.

That's incredible to me.

But it is minimal compared to what other people within Hachette are doing. You know, it's very flattering that you're talking to me, but you should talk to Megan Tingley, who discovered Twilight. That is carrying the company. Talk to Little, Brown about the way they've built up Malcolm Gladwell over the years. That's been an extraordinary job of publishing. Jamie Raab has arguably the best track record of anyone in the industry: Nicholas Sparks, Jon Stewart, Stephen Colbert, Michael Moore, a number of Oprah picks. It's an incredible track record. So this is a company that has a lot of acuity, specifically with regard to acquisition and marketing.

I have a highly original question for you. In the first few years with Twelve, what has surprised you the most, what has enchanted you the most, what has humbled you the most, and what has troubled you the most?

Wow, that's a long one.

It's the question Jeff Zeleny asked Obama after his first hundred days, and Obama took it seriously because he was on TV and didn't have any choice. But you can dodge it if you want.

No, I'll answer it, although I'm worried that I may lack Obama's introspectiveness. I guess I was surprised that it took me as long as it did to get books into the pipeline. When I started the imprint, the idea was to do four discoveries, four midlist books that could take off, and four books that were so obvious that a monkey could publish them. I had no trouble with the discoveries or the midlist books. Surprisingly, there were a lot of other people who wanted to publish the monkey books.

Big surprise to you? [Laughter.]

I was surprised. I thought there would be enough of those obvious books that I would acquire them very easily. But it turns out that this simian mentality is pervasive. So I was surprised by that.

I was enchanted by the success of God Is Not Great, because it came from such a sincere place. I was having lunch with Steve Wasserman. He was a new literary agent and I was a new book publisher. He told me that he was working with Christopher Hitchens. I said, "I've been a fan of his for years." In fact, I'd gotten his email address from Christopher Buckley and was going to propose that he write a book about Congress. Steve said, "Well, no, he doesn't want to do that. I think he's going to write a book about the case against religion." My eyes lit up. Because ever since 9/11, I've been one of these people who was pointing the finger of responsibility at religion—all religion—for inculcating violence in the culture and, at least in politics, a false sense of piety. After lunch I came back and talked to Jamie Raab about it and we decided to just put money on the table, right then and there. He didn't talk to any other publishers. He didn't do a proposal. We just bought that book based on a lunch conversation. I don't think I even talked to Christopher about it. The manuscript came in and it was one of those books that you read and want to go out and tell everybody about. You want to proselytize. "You've got to read this book! It'll change your view of this!" And it immediately took off. So that was an enchanting experience. Any time you have a number one best-seller, it had better be enchanting. [Laughter.]

I was humbled when we published a book called The Film Club, because we did everything right. The sales force loved it, independent booksellers loved it, the media loved it. We got rapturous review attention, we got the author on network TV, we had him all over the radio, we toured him. And it still didn't break out. It sold well—we made our money back and I think it's going to have a long life in paperback—but The Film Club was one of these books that I thought could have sold a million copies. I felt like it had everything. It was a really well written, engaging, and moving story about a relationship that I thought almost anybody could relate to, and yet it was also unconventional. I mean, the idea of a father agreeing to let his son drop out of school if he would just watch movies with him? It was a story that stuck to me, and I was sure I could get it to stick to other people. And it humbled me because it reminded me, once again, just how hard it is. At that point we'd had a few best-sellers in a row. Everything was working. I was sure that this one was going to catch on, and it just didn't make the best-seller list. I wish it had.

I was troubled, like everybody else, by the layoffs in the industry. I was troubled by the number of really good, hard-working editors who were let go for no reason other than a bad economy. I was deeply troubled by that, and there but for the grace of God go all of us. But then again I'm an atheist so I guess I should put it another way. There but for the grace of Hitchens go all of us.

Can we talk briefly about the piece you wrote for Publishers Weekly that offered twelve steps for better book publishing? One of your suggestions was "imprints for everyone."

Yes, I believe that. I think that the editor is the best publisher of the book.

So why don't more publishing houses do it?

Some of them do. Penguin has that model, to some degree. Reagan Arthur has an imprint. Megan Tingley has one. I think that it may become more prevalent. But why don't more companies do it? I suppose that you need to have entrepreneurial editors. And when I say that the editor is the best publisher, I should expand that to say that I think the editorially driven publishers are the best ones. I think you can be a marketing person with a great editorial sensibility. But I think it has to begin with what's on the page.

I think that some editors may not want the responsibility. And some editors may not be ready to assume that role because they're more interested in the text than in the world into which the text is launched. It requires a certain kind of sensibility. But I also think that the principal reason there aren't more imprints is probably because a lot of publishers are reluctant to let go of their power and trust it to other people. That's a difficult thing to do for some people. When I was a senior editor at Random House, working for Ann Godoff, I felt like I was the publisher of those books as much as she was—because she had the confidence and the generosity of spirit to share in that endeavor.

Another idea you talked about in the piece is that if a book that is bought on proposal doesn't deliver on its promise, we should give the author the chance to take it elsewhere. If that isn't possible, we should publish it as an e-book or print on demand with no marketing. Did you hear from agents about that idea?

I didn't hear any criticism from agents but that's because—with all due respect to agents—to their eyes I am a human ATM machine. They need to push the right buttons for the money to come out, and telling me that I am moronic might not serve their best interests. However, I would like to say to all those agents that I'm happy to be called a moron. I welcome criticism, and I actually respect people even more when they tell me the truth. The only criticism I got from an agent was from someone I deeply respect, Heather Schroder at ICM, who called me up and said that she didn't agree that there should only be one bidder at each company. And I respected her for having the candor to say that to me.

Another thing you wrote somewhere is that all good stories are about transformation. What else would you add to that in terms of your ideas about storytelling in the big picture?

The thing I drill into writers all the time is this idea of deep immersion into your subject, and real command of it, and authority. That's the quality that any discerning editor immediately cottons to. Beyond that, I don't think writers often enough appreciate just how important it is to be conceptually distinct. If you're talking about fiction, it's always struck me as elemental that a novel should be novel. So I've never understood why somebody would write a novel knowing that the story has been done millions of times before. If your work is not novel on the conceptual level, I'm not sure why you should expect somebody to stop what he's doing and pay attention, given the vast opportunities for distraction in society.

I was struck by something I read years ago in an interview with Norman Mailer, who said that if he'd gotten started later in life, he probably would have been a movie director so he would have had more influence. He also said that he thought novelists would eventually have the cultural influence of landscape painters. I'm not saying that I agree with that. I just think it's interesting that a writer of Norman Mailer's stature would recognize how difficult it is for fiction to maintain its cultural centrality or impact.

So if you're setting out to write a novel, or literary nonfiction, for that matter, I think you have to have very high standards. Now, I say that—and I mean it—but I also understand that not every reader is coming to a book with the very high expectations that I seem to have for just about everything I read. I suppose if you're just looking for something to escape with on an airplane, you can set the bar a little lower. But I would still ask the same question: Why your airplane novel rather than the five thousand others that are published every year?

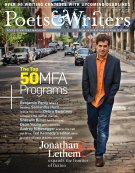

This is the magazine's MFA issue. Do you have an opinion about MFA programs?

I think they're great, and here's why: Writers need a support system for developing their work. I also think, to be realistic, writers need economic support. These MFA programs provide it for both graduate students and teachers. I don't know very many novelists who support themselves solely through their fiction. Even the most successful novelists I've worked with usually have other jobs, either in academia or in the media. I think that's very useful. It provides balance and keeps you from losing touch with a certain aspect of life. It also probably makes you happier. It's funny, I read an interview with Tom Clancy in which he described his life as a miserable existence of time in solitude confronting the limits of his imagination. Now maybe he was just in a bad mood the day he gave that interview. But all the research on happiness indicates that social interaction is to our benefit, and, therefore, it might behoove writers to get out into the world a little bit more. I think it results in better fiction.

You have a unique perspective on editors. Put yourself in the shoes of a beginning writer who is lucky enough to have multiple offers and has to decide which editor to go with. What advice would you give her about navigating that situation?

I think you should reduce it to the simple question of "Who can you best imagine yourself conversing with on a regular basis over a sustained period of time?" If you're intimidated or bored or uninspired by the editor, those are easy reasons to eliminate people. Obviously it always helps if the editor says something that is meaningful or significant about your work. That is usually a good indication of a shared sensibility. You also might want to think about what happens if that editor leaves, because that happens to a lot of writers and I think it's good to deal with it up front—to know that there's at least one other person at the company who's a real advocate for the work. A lot of authors get orphaned and think it's the reason their book hasn't succeeded. It usually isn't the reason, but that's what they think. It's important to know that somebody else at the company will stand behind you if your editor leaves.

Tell writers something you know about agents that they might not know.

I would say to listen to them. I'm surprised at how often authors, even published authors, fail to hear the nuance in what their agents are telling them and are too quick to follow their own needs rather than what their agents are telling them to do. I have very rarely seen agents give authors bad advice. The longer I've been doing the job, the more I realize that usually the agent knows that the book doesn't work or the proposal doesn't work but they've had to submit it because they didn't feel they could put the writer through another draft—because either the writer was balking or they didn't think the writer could handle it.

Writers probably think that agents have all the power and they have to do what their agents say. But the reality is that a lot of agents are very sensitive to either alienating the writer or causing a crisis of confidence. So the agents begin to walk on eggshells. I think that writers should be very aggressive in seeking the truth from their agents. I'm always struck by what authors tell me about their work. They'll say, "My friends tell me they love it!" I feel like saying, "Did you really, really drill down and ask your friends what they really thought? Did you force them to tell you one thing about it that they didn't like? Can you handle the truth?" Frequently, the writer hasn't done that. It's hard to tell the writer when something isn't working, and some agents don't always articulate it quite as clearly and forcefully as they should, largely because they know they're dealing with a delicate ego. So my advice to writers would be to aggressively seek the truth—forget about your ego—and do one more draft than your agent asks you to. The writers who I have noticed being successful are the ones who are making their agents wait for that next draft. It's the authors who don't pursue that next project until they're sure it's the right one for them. It's the ones who turn down the easy overture from the publisher for the quickie book and wait to do the book that they can really commit to.