Poems are weird and unruly. Writing personally about them, bringing my life into collision with their power, feels like a risk to my professional credibility because I was trained to strike a pose of objectivity in the classroom and in my critical writing. But if impersonality were simply an expectation of my academic field, I might have ditched this posture sooner. In truth, my sense of poetry’s hazard cuts deeper. Poetry can break the skin of your life—but it can heal you too.

Exposure hurts. When, for instance, I was a kid humming to myself on a Long Island sidewalk, another girl rammed me with her banana-seat bike. The fender bit into my thigh and whitish flesh jiggled inside the gash. Three pregnant mothers from the block scooped me up and drove me to the ER, one of them having slid into the backseat with me without even removing the bobby pins from her spit-curls. Holding my skin together with a bloody washcloth, she whispered, “You’re being so brave. You’re such a brave girl.”

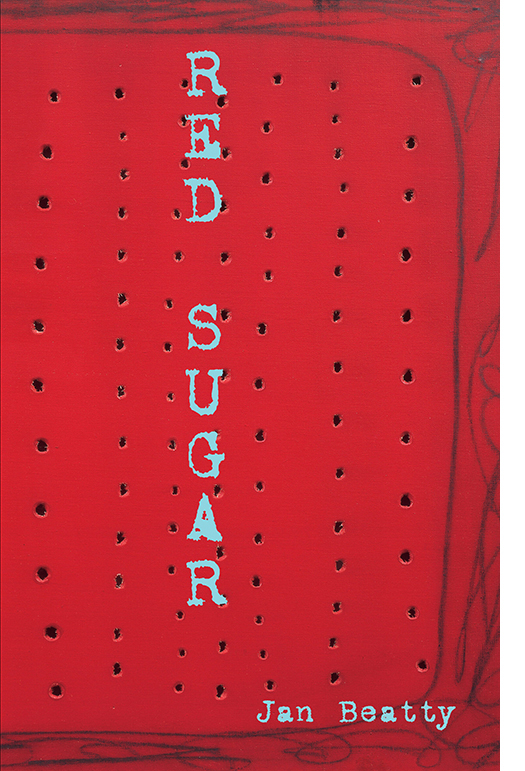

I remembered that hospital trip when I first read Jan Beatty’s “Red Sugar,” the title poem of her 2008 collection published by the University of Pittsburgh Press. Beatty’s poem describes inner life in a startling way:

I didn’t know until I was

twelve that we carry other bodies inside us.

Not babies, but bodies of blood

that speak to us in plutonic languages

of pith and serum.

Reading the poem is to follow Beatty as she learns to listen to herself. She meets a naked man in the woods and identifies the danger he poses with her “inside body,” a “red sugar body.” Later in the poem, when she spots a possible relative, that inside body advises her again, this time to approach the oddly familiar stranger: “the red sugar says, go.” The stranger denies the relationship “but both / our inside bodies knew she was lying.”

Beatty’s red sugar imagery infected me immediately. Sometimes when you encounter a poem its metaphors or rhythms entrance you and rivet your attention to another space and time. When that happens, another person’s thoughts, feelings, and memories seem to invade yours, and the experience changes you, if only because reading makes them your memories too. This is why Richard J. Gerrig, Keith Oatley, and other cognitive scientists describe a reader’s absorption in a text as performance, enactment, or even a simulation running in their mind. As a reader, you imagine settings and characters based on slight textual clues and make projections about how a story will unfold. Imagery might trigger sensory involvement, the way a vivid description of a meal can make your mouth water. The poem gives you access—or seems to give you access—to another person’s inner life. Through what’s called “literary transportation,” even as reading allows you leave your messy body behind for a while, the process can give you insight on how to inhabit it more profoundly.

The childhood Beatty portrays in “Red Sugar” is unlike mine. It doesn’t erase those differences to say I feel moved by her work, even, in an uncanny way, recognize her experience of it. She endured too much erasure as an adoptee, as her recent memoir, American Bastard (Red Hen Press, 2021), makes abundantly clear. I wouldn’t want to worsen that erasure, as a critic or as a human being (why do I treat those as separate identities?). Yet the central image in Beatty’s poem is now inseparable from the way I think about the selves within myself. Ruptured me, fearful me, teacher me, daughter me, and others assemble in my brain like a spiritual microbiome that controls my decisions in ways I can’t always detect. Beatty’s poem names my instincts about other people, too, and emboldens me to trust intuition. Ignoring those instincts of mine can be dangerous; “Red Sugar” warns me about liars and bullies and worse.

I approached a horizon in my writing about poetry during a 2011 Fulbright in New Zealand—talk about distance. I was beginning my research when, back in Pennsylvania, my parents’ marriage imploded. The news shocked me and estranged me from myself, and learning it while far away was lonely. My father was finally losing control of his secrets: how he’d gambled away my parents’ retirement savings in bad investments; his string of extramarital affairs which, bizarrely, he documented in three-ring binders shelved in his home office; and his latest romance, with a senior center aide four decades younger than him. My intensely private English mother hated the ensuing revelations. “I kicked him out of the house,” she e-mailed during my first month away, “Don’t tell anyone.”

I wasn’t sorry about their divorce. He was a liar and a bully and worse, the person who trained my red sugar in the first place. But I suddenly saw myself as a network of stories, like one of those people in an anatomical diagram, composed of red and blue veins and arteries. Some of the stories had ruptured.

I kept reading poems, grateful for how the feeling of flow I experienced calmed my heartbeat and respiration, my body as well as my mind. I also consumed psychology and narrative theory. I wouldn’t have thought I would be immersed in them so thoroughly but I was. Why, I wondered, did studies of “literary transportation”—getting lost in a book—focus almost entirely on the twisty plots of long novels, as if short poems don’t also create alternate possible worlds? Wasn’t I living in them, perceiving my past through their red mist?

My father died alone in May 2012, having alienated his new wife by stealing rolls of her cash—she didn’t trust banks—and burying them in baggies all over her yard. In the months afterward, I drafted the first chapter of something new, exploring how Beatty’s “Red Sugar” carried me away. I kept writing as my father haunted my dreams, my children grew up and left home, harassment poisoned my work life, and, eventually, my mother got sick, a tumor swelling in her belly like a monstrous baby.

My mother’s death freed me to tell painful stories, but I carry her silence inside me too. In New Zealand I was an alarmingly frank American, but in the U.S., people are always telling me how reserved I am. It seems to me that I’m bleeding all over the place, leaving a trail of stained pages, but friends tell me no. Say more about how your father hit and mocked you, how your mother stepped back and betrayed you, how decades later a gaslighting boss woke that memory and your colleagues closed their doors. Why you won’t put faith in anything but literature.

During my bloody childhood trip to the ER, my mother’s friend tried to give me courage by calling me brave. I haven’t always lived up to the word. Writing a memoir about reading and grieving is a small risk, in the scheme of things, but it did take some courage. The years I spent drafting and revising it felt both like listening to the voices inside me—a liberating thing—and prying open wounds and trying to describe what’s inside them—too painful for language. Immersing myself in poetry and even in writing about it had an escapist aspect, sure, but it also represented a self-validating return. I was struck by a bike that day because my mother insisted I play outside instead of hanging around on a couch alone, bearing a book like a shield. I’m an anxious introvert who has always used books as medication. Now the science makes that look like a pretty canny strategy.

Yet good poetry isn’t safe. Not despite but because of its small interiorities, it enables a scalding intimacy that isn’t available in other genres. You feel the poet’s impossible, devastating presence. Then you step back into your own world, braver, transfused.

Lesley Wheeler is the author of Poetry’s Possible Worlds (Tinderbox Editions, 2022), Unbecoming (Aqueduct Press, 2020), The State She’s In (Tinderbox Editions, 2020), and other books. The poetry editor of Shenandoah, she lives in Virginia.

Author photo credit: Anne Valerie Portraits