This past weekend, as the sidewalks and the streets of midtown Manhattan once again began to fill with urban dwellers lingering in the first warmth of spring, some of New York City’s writers and publishers found pause indoors, creating, investigating, and celebrating the little sibling of the poetry collection: the chapbook. The Festival of the Chapbook was a movable feast, from a book fair and reading in a brightly lit recital hall at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center to a roundtable and panel discussion in the warm, homey loft space of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop (AAWW) in Koreatown, with the Center for Book Arts (CBA) in SoHo hosting bookmaking sessions in between.

On Thursday evening, poets Lytton Smith, Gerald Stern, Judith Vollmer, and Kevin Young, each with his or her own connection to the publication and dissemination of chapbooks, gathered in the Graduate Center for the festival’s keynote reading. Smith commenced the reading with poems from Monster Theory, which was selected by Young for the 2007 New York City Chapbook Fellowship, sponsored by the Poetry Society of America (PSA). [In the interest of full disclosure, my chapbook, Ave, Materia, was selected for the award in 2008.] Smith’s little book is saddle-stapled with a matte cover patterned in wood grain, a design for which he thanked book artist Gabriele Wilson in absentia. As Smith was reading, just as he uttered the line, “Leave your instruments at the entrance,” my cell phone began to vibrate audibly against the floor beneath my seat and, in a way, I thought, against the small, quiet moment of poetry that encompasses the spirit of the chapbook.

Phone switched off, I and the other listeners sat in quiet anticipation as Stern unpacked his papers from a canvas bag and slowly, carefully arranged his things on stage, the scene resembling “an old silent movie,” he quipped. Stern’s chapbook Last Blue was published by festival sponsor and chapbook champion CBA in 1998, as he was a judge for that year’s competition. (He selected James Haug’s Fox Luck for the award.) After instructing the audience, in the interest of time, to “start booing a little past ten of seven,” Stern began reading from his many “poems about shoes,” but not before explaining the fascination: “It’s the lower world I’m interested in.” It was an apt comment, considering the chapbook form’s traditionally underground appeal and mode of production. (Although the chapbooks being celebrated were published by relatively sleek and professional processes.)

Vollmer, winner of the CBA award in 1998, followed. Like Smith, she commented on the design of her book, a deep blue cover that mirrored the poetry in the book. “I was trying to write about water,” she said, explaining that as a writer living in Pittsburgh her work has been affected by the three “untouchable” rivers there. Because of the chapbook form’s diminutive nature, the relationship between their design and content is significant, and a beautifully designed little book is a thing treasured by author and reader.

Young closed the set by reading a poem on Johnny Cash called “I Walk the Line.” As he introduced the poem, correcting himself after referring to the musician as “Johnny” and revising his address to “Mr. Cash,” a bit of phone interference hopped across the speaker system. Acknowledging another tiny moment of cellular-poetry synchronicity, someone from the small but attentive audience whispered, “It’s Johnny.”

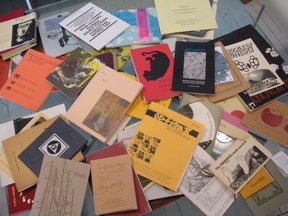

I revisited the festival on Saturday at the AAWW, where historian and marketing director Patricia Wakida of Kaya Press, a publisher of literature from the Asian diaspora, was moderating a roundtable called “The Collector’s Show-and-Tell: The Secret History of Asian American Literature.” She had spread out on a low table an array of handmade and professionally printed little books. A volume that immediately caught my eye was a long, rectangular book bound a few inches left of center with two short screws that resembled the rivets on a pair of jeans. If opened on the right side, the book appeared to contain only a collection of poems, but to the left of the binding, where one might not be inclined to look for content, were hidden a series of black-and-white photographs. Several of us responded with a delighted “oh” when Wakida held the book up and flipped open what I had assumed was a blank margin. Another compelling book featured an embossed print of a girl’s silhouette on the cover, and the pages, so pleasing to touch and leaf through, were of a sort of brown-bag stock that felt worn like fine leather.

Comments

Motherscribe replied on Permalink

Sounds like an amazing celebration of the Chapbook