A few years after Junot Díaz made a huge splash on the literary scene with his debut, Drown (Riverhead Books, 1996), a story collection published when he was just twenty-eight,one of his good friends, Francisco Goldman, began to worry. It'd been a while since anyone had heard from the young writer. He'd placed a few short stories here and there, but mostly Díaz was spending his time teaching at Syracuse University, up in the snow-covered farmlands of central New York. After Drown, it was the only job offer he'd gotten, and he'd taken it.

Díaz worked hard, but still the novel moved slowly on most days; not at all on others. He had written thousands of words. For most writers that's called writing. But for Díaz it only counted if he wrote something he loved.

But Syracuse was a long way from anywhere for the writer, who was born in Santo Domingo, in the Dominican Republic, and immigrated with his family to Parlin, New Jersey, at the age of six. Díaz loved being in the mix, living in the city—all the people, all the energy. Now he was alone, working in a cold, postindustrial relic of a city. It was taking its toll on his work.

Maybe it was that. Or maybe it was the million lights shining on him after Drown became such a phenomenon. Once an unknown writer, Díaz suddenly found himself standing at lecterns and accepting awards. He was picked by Newsweek as one of "the new faces of 1996." Caught up in the buzz, he watched his book go through printing after printing. Maybe it was all that. Or maybe it was that Junot Díaz expected more of himself than any of his critics or fans.

Whatever it was, things weren't going well. Díaz was barely writing. Or he was writing, but nothing good. Nothing clicked. Nothing gelled. Nothing really set him on fire. And he could find nothing in his notebooks that would make his follow-up bigger than his debut.

Meanwhile, Goldman—a novelist whose first nonfiction book, The Art of Political Murder: Who Killed the Bishop?, is being published this month by Grove Press—was on his way down to Mexico to hole up in an apartment and write, so he called Díaz and asked him to come along. "I'll never forget what he said to me," Díaz remembers. "He said, ‘You're up at Syracuse, falling on your sword. You need to get away from there, come to Mexico City. It's an amazing city. It's problematic and beautiful. It's exactly the things you love.'"

Díaz had recently received a Guggenheim Fellowship—another in a long list of honors received after the publication of Drown—so he took a sabbatical and flew down to Mexico City, where the two holed up in adjacent apartments and worked on their projects. Goldman worked on his novel, The Divine Husband (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2004), and Díaz hammered away at his work-in-progress, what he called his "Akira" novel—inspired by the Japanese comics series and 1987 film of that name—about the destruction of New York City, its aftermath, and the survivors.

It was a good time. Together, the two writers worked hard in their respective spartan apartments. Díaz kept the sun out by taping garbage bags over the windows and blasted hip-hop. In the evenings, they would go out to restaurants, or hang out at the mall, or go see bad Belgian sci-fi movies. Then they would head back to their apartments to work.

Díaz worked hard, but still the novel moved slowly on most days; not at all on others. He would go over to Goldman's and tell him that he hadn't written a word, even though he had filled notebooks. He had written thousands of words. For most writers that's called writing. But for Díaz it only counted if he wrote something he loved.

Then, when he least expected it, someone appeared in his apartment with him: Oscar Wao. Years later, he would become the main character of Díaz's long-awaited second book, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, published this month (September 2007) by Riverhead.

If you ask Junot Díaz, who is now thirty-eight, when all of this happened, he can't tell you exactly, because he doesn't remember years. He doesn't remember dates. He doesn't remember lengths of time.

"Journalists hate me," Díaz says, explaining that he can't remember things like how long he taught at Syracuse, or when he went to Mexico, or in which issues of the New Yorker his stories have appeared.

But he does remember one number: eleven. That's how many years it's been since Drown was first published and Díaz became the wunderkind Latino writer from whom all great things were expected. That's how long it's been since Newsweek lauded him for having "the dispassionate eye of a journalist and the tongue of a poet." That's how long it's been since he went from being an unknown who worked at a temp job as the copy-machine boy at Pfizer to an international celebrity.

The world seemed to have been waiting for Drown, which is now in its twenty-first printing. The book is a spare and brutal and tender collection of interconnected stories, each one an emotional iceberg, their simple surfaces concealing the depths below. They seem to say so much about everything, from immigration to identity to race to sex, by hardly saying anything at all.

Half the stories are narrated by a character named Yunior de las Casas, a tough kid who immigrated to America from the Dominican Republic at age nine. Drown reads almost like a photo album of Yunior's life and the lives of the people around him. The language is spare, and yet deep down, beneath it all, the book is a veiled retelling of the Odyssey through the eyes of Telemachus and Penelope. After all, the ultimate odyssey is immigration—the journey at the heart of the book.

A reviewer for the Washington Post Book World described Díaz's literary voice as "unique, vibrant and poetic." In the Guardian newspaper in London, Francisco Goldman—who had not yet met the author—wrote, "The language is a revelation, the very soul of a new identity. It is Díaz's own, but also that of a new kind of ‘American.'"

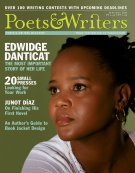

Edwidge Danticat, author of Brother, I'm Dying (Knopf, 2007), who comes from Haiti, on the other side of Díaz's native island, remembers when she first read Drown: "It was just a surprise," she says. "A breath of fresh air. I think what people said about him was really true, that he was a bold new voice. He was going places people hadn't really been."

"I think his writing is a very direct expression of who he is personally, which is maybe why it's so powerful," says award-winning fiction writer George Saunders, who taught with Díaz at Syracuse and whose first essay collection, The Braindead Megaphone, is also being published this month by Riverhead. "Like him, it's full of beautiful contradictions; it's tough and lyrical, tender and fierce, angry and in love with the world."

That may be one reason why Díaz's follow-up took so much of his sweat and blood—and there's one other reason.

"When you start young and you do well in the beginning," says Danticat, "you always feel that pressure. It's not just that your work will be looked at. It will be looked at in a certain way. People want you to live up to—or surpass—what you did with your first book. And creativity is a fragile thing."