First published in 2004, Claudia Rankine’s Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric introduced a genre—fusing the lyric, the essay, and visual elements—uniquely suited to exploring the personal and political unrest of a volatile new century in America. The first title in what would become the best-selling and widely acclaimed American trilogy, along with Citizen: An American Lyric (2014) and Just Us: An American Conversation (2020), all published by Graywolf Press, Rankine’s groundbreaking book offered a guide to surviving the enduring anxieties of medicated depression, race riots, divisive elections, terrorist attacks, and ongoing wars. “Rankine breaks out of virtual emotion, reawakens honesty, and exhibits such raw political courage and aesthetic bravery it sends tremors through the entire field of American poetry,” wrote Jorie Graham. Now, twenty years after its initial publication, a new edition of Don’t Let Me Be Lonely featuring new material, including the following preface written by Rankine, has been published.

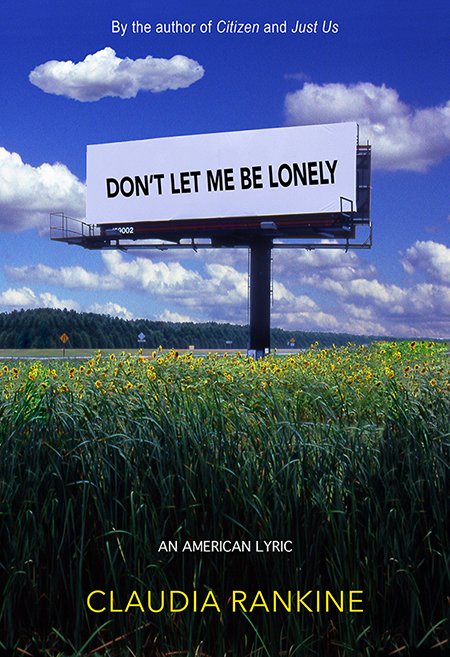

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric (Graywolf Press, July 2024) by Claudia Rankine

![]()

I first began working on Don’t Let Me Be Lonely in Paris in 1999 during the run-up to the turn of the millennium and the George W. Bush presidency. It was my sabbatical year from Barnard College and I was living in the Southwest of London. That fall, in Paris for a long weekend, I remember strolling by a café table and reaching out for a paper napkin in order to write down some thoughts. By the time I returned to our rented house on Whittlesey Street near Waterloo Station, I was writing in a notebook what seemed to me to be episodic meditations on what it means to live simultaneously in community and in isolation.

I deliberately wrote from a position of incomplete knowing and understanding, not knowing exactly but feeling completely. I allowed hesitancy, worry, fear, apprehension, and need to be my subjects wherever I saw, heard, or felt any or all of these emotions. The pieces became a collection of movements in the historical present that I witnessed in my own life and in the lives of others in both very public and very private arenas. I went from thinking about the pieces as meditations on events to laments in real time. Eventually, I began to understand the writing as emotional expressions of moments in time and not so much records of a singular life. These were lyrics holding historical affect. Loneliness and violence were flooding our days, or so I felt. Fear was driving both our actions and stasis. For some of us, the fear was an excuse for cruelty, and for others, fear was synonymous with terror. Loss was the same as it ever was.

It is an understatement to say that Lonely was a watershed moment for me as a writer at that time. As I sat in my office on the second floor of what was once a dockworker’s home in Lambeth by the Thames, I knew the new work differed from my three previously published books. The same training that produced those books informed this new project, with one difference: I wasn’t self-consciously experimenting with the possibilities of language; I was consciously representing a world as I both saw and felt it, and therefore, the bullshit notion that politics have no place in poems had to be understood as self-erasure. To write, while fully knowing, seeing, and feeling, meant I needed to take what was needed formally and theoretically from the two dominant poetry traditions of the time and let the rest go.

To oversimplify, I will say I was positioned between the theory-driven Language poetry and the tradition of inward-turning writing often described as overheard emotion. The contemporary white writers dominating the poetry landscape at the end of the twentieth century neither saw that their whiteness was political nor that the world was dedicated to their white supremacy. Consequently, it was beyond their abilities to understand how their whiteness informed their writing and their poetics; most maintained a level of uneducated, willful unconsciousness that made little sense but held all the power. This was true on both sides of the aesthetic divide within the two dominant poetic communities but in different ways. (I felt this in part because I had co-chaired a conference with Professor Allison Cummings at Barnard entitled “Where Lyric Tradition Meets Language Poetry: Innovation in Contemporary American Poetry by Women,” in April 1999, in an attempt to address how siloed and segregated both communities were, on and off the page.) My intention was for Lonely to put pressure on the dominant lyric model while holding onto the modes of writing that made apparent the power structures inherent in language use underlined by some of the work of the Language poets. I also was interested in attaching affective frequencies or a grammar of interiority to some of the Language poets’ more theoretical approaches.

In as much as Lonely has a backdrop, it is New York City under the mayorship of Rudolph Giuliani at the change of the millennium. The Supreme Court had inserted itself in the 2000 election by overturning a state law requiring a recount in Florida where an illegally narrow margin of 537 votes awarded the state for Bush, thus handing him Florida’s twenty-five electoral votes and the presidency. If the Supreme Court had seemed a safeguard of our democratic practices, I regarded it quite differently after that election, given the infrequency with which a president won without the popular vote, a dynamic that would be repeated in the election of Donald Trump in 2016.

When the clock struck midnight to start 2000, the Y2K problem was solved with a four-digit number. The fear and terror that had built our American culture would broaden in scope with the 9/11 attacks and the destruction of the World Trade Center in 2001. The obvious misinformation circulated by the Bush Administration and peddled by the Fourth Estate in our rising forms of new digital media eroded any trust in journalism and our understanding of facts. The writer Susan Sontag would point this out in an essay in the New Yorker regarding America’s response to 9/11:

The voices licensed to follow the event seem to have joined together in a campaign to infantilize the public. Where is the acknowledgment that this was not a “cowardly” attack on “civilization” or “liberty” or “humanity” or “the free world” but an attack on the world’s self-proclaimed superpower, undertaken as a consequence of specific American alliances and actions? How many citizens are aware of the ongoing American bombing of Iraq? And if the word “cowardly” is to be used, it might be more aptly applied to those who kill from beyond the range of retaliation, high in the sky, than to those willing to die themselves in order to kill others.

On May 19, 2022, former president Bush would inadvertently agree with Sontag in an attempt to condemn Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine: “The result is an absence of checks and balances in Russia, and the decision of one man to launch a wholly unjustified and brutal invasion of Iraq—I mean of Ukraine.”

This realm of media-world-building ultimately determined the structural form of Lonely. The oversized vertical format and black-and-white images of the original publication in 2004 were meant to speak back to newspaper columns and opinion pieces. The new edition, published twenty years later, has moved into full color to acknowledge the shift to online media with an updated screen that functions both as television and computer screen. The present importance of the documentary image captured and circulated by phone has informed the replacement of some illustrations in the text, though many original illustrations remain.

The use of the first person throughout Lonely is a strategy I came to in an attempt to maintain a form of intimacy and agility within the prose poems themselves. The first person seemed more a rudder than an authentic self as I had been schooled to believe it should be by the traditional lyric. The agility and fungibility of a single subjectivity allowed the voice of these pieces to roam the landscape of the book’s experiences, which exist beyond the experiences of my own life. “I” was there to signal a disembodied speaker in the sense that it could inhabit multiple bodies experiencing or looking on or being alongside. To answer a question of the poet Paul Celan, “I” was there to bear wit- ness to the witness. I, Claudia, was not the woman on the roof, but there was a woman on a roof having the experiences that we as readers step into. Anybody could embody the first person and be our guide through the text. For me, at the time, this was a liberating mechanism for getting at the ineffable affective disorder of the moment without dis- connecting from the people affected by it. “I” was able to exist within everyone’s quotidian, the one I knew intimately, the one in the television, the one running for office, the one documenting the moments, the one running the country, the one in books, and so on.

The added notes were placed at the end of the book to underline the lyric nature of the pieces. Lonely was fictive though everything had happened. The notes held the facts as they were known at the time. I wanted to separate the affective orientation from the factual information. No attempt was made to correct memory in the body of the text. Someone said this thing. Someone did this thing. I wanted to follow them emotionally, not factually. Affect forms within the feeling of what we feel we know. How we enter the generalized experience is mostly partial and episodic. In the end, because we are here together, our private feelings are informed atmospherically and grounded in our collective chronic conditions. How we give shape to the memory of that might not be factual, but its shapes inform the truth of the feeling and of the times. The notes reinforce an acknowledgment or a recognition within the body of the text that there is always more to know or another way of knowing or no other way forward for memory.

Lonely was a stand-alone collection until it wasn’t. When Graywolf asked me to frame the title, I wished to underline the political nature of being as “being itself” within the writing of poetry. There is no outside of the politics that shape the quotidian. The fact that white people presented their lyric poetry as beyond politics was itself political. The poet Richard Howard had referred to the poems in Lonely as “lyrics” in a note he wrote in support of the original manuscript, and my own desire to firmly embed them in our history of white supremacy and capitalism necessitated the addition of “American.” Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric was followed ten years later in 2014 by Citizen: An American Lyric and finally in 2020 by Just Us: An American Conversation. The trilogy taken as a whole covers the time from 1999 to 2020, more than two decades of violence and hatred in an increasingly divided nation under the leadership of presidents Bush, Obama, and Trump. Following the 2010 antigovernment protests in the Arab world known as the Arab Spring, protest movements like Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, and #MeToo all insisted on a more integrated and accountable assessment of America’s anti-Black, misogynist, white supremacist, patriarchal, and capitalist impact on our daily lives. Following Lonely, Citizen and Just Us attempt to both reflect and forge conversations in light of our daily struggles with the power structures limiting our possibilities and reframing our realities. Many readers came to the trilogy through the door opened by Citizen’s publication. The reissue of Lonely is a look back at where the concept of the “American Lyric” actually begins.

Claudia Rankine is a poet, essayist, and playwright. She is the author of the celebrated and best-selling trilogy of Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, Citizen, and Just Us. Rankine is the recipient of the Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry, the 2014 Jackson Poetry Prize, and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Lannan Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, United States Artists, and the National Endowment of the Arts. She teaches at New York University.