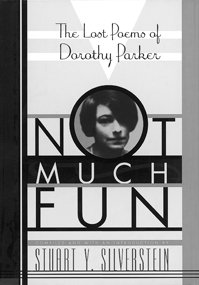

On April 4, United States District Court Judge John F. Keenan ruled in favor of Stuart Y. Silverstein in a plagiarism suit he filed against Penguin Putnam in 2001. Silverstein, who compiled Not Much Fun: The Lost Poems of Dorothy Parker (Scribner, 1996), claimed in his lawsuit that Penguin infringed on his copyright by publishing Dorothy Parker: Complete Poems, which includes a section titled “Poems Uncollected by Parker,” the identical poems published in Not Much Fun.

According to Silverstein, in 1994 he submitted a manuscript of Parker’s lost work for potential publication. Silverstein had spent more than a year reading through back issues of publications from the 1920s to the mid-1940s, collecting and editing what he deemed poems by Parker, including poetic fragments in book reviews and a short rhyme in an advertisement for a book by poet Ogden Nash. Penguin offered Silverstein $2,000 to publish the compilation as part of a larger collection, which he declined. He then took his manuscript to Simon & Schuster, which published the poems and introduction by Silverstein as Not Much Fun under its Scribner imprint.

When Penguin published Complete Poems three years later, it was evident to Silverstein that Penguin had used his material for the last section of its new book without attribution or compensation, so he decided to sue the publisher for copyright infringement and for false designation of origin (the failure to properly attribute the work to Silverstein) under the Lanham Act.

To prevail on his claim, Silverstein had to prove he had ownership of a valid copyright and that Penguin had copied the material. Silverstein had already obtained a copyright for the compilation in 1996, but Penguin’s lawyer, Richard Dannay, argued it was invalid because Silverstein’s book was not original material and therefore not entitled to copyright protection.

In order to establish that his copyright was valid, Silverstein had to convince the court that his collection was original. Silverstein argued that in addition to the approximately 600 changes he made to the poems, he arranged, titled, and selected which works to include in the book and that his selection and coordination reflected sufficient creativity to satisfy the requirement of originality under copyright law.

Silverstein further claimed that the editors at Penguin copied his work comma for comma, and went to great lengths to intentionally obscure the fact that the collection came from his book. For example, he asserted that in keeping consistent with the pattern Penguin chose for naming the first five sections of the book (“Enough Rope,” “Sunset Gun,” “Death and Taxes,” “Death and Taxes and Other Poems,” and “The Portable Dorothy Parker”), which are all titles of previously published Parker collections, the sixth section should have been titled “Not Much Fun,” because the poems in this section were also part of a previously published compilation—the one Scribner published in 1996. Instead, Penguin titled the section, “Poems Uncollected by Parker.”

“They didn’t even call it ‘Uncollected Poems,’ because that would have been inaccurate,” Silverstein said. “They had been collected by me.”

“A Note on the Text” in Penguin’s Complete Poems states that the poems were “faithfully reproduced from Dorothy Parker’s original collections.” It goes on to list her works without mention of Silverstein or Not Much Fun, which the judge saw as a direct violation of the Lanham Act, a law that basically forbids selling another author’s product as one’s own.

Penguin didn’t deny copying the book; instead, it contended it didn’t owe Silverstein attribution. Colleen Breese, author and editor of Complete Poems, testified to buying Not Much Fun and, with the exception of one poem, photocopying the material and submitting it to Penguin to be used as the “Poems Uncollected by Parker” section of the book. According to a court document, in the earlier stages of production Breese wrote to Penguin senior editor Michael Millman in reference to Silverstein’s work. She stated that she did not want to “direct people to the competition,” and therefore refrained from crediting him as a source.

Dannay argued that Silverstein’s work was a discovery of a fact, and facts are not protected by copyright law. “For material that is either in the public domain or is not subject to copyright protection, there is no legal and no ethical obligation to refrain from using it,” he said. “And if by using it, it means photocopying it, or scanning it, or using some other reasonable basis for simply using material you have a right to use, then I don’t agree it’s unethical.”

Judge Kennan apparently disagreed. According to his decision, Silverstein’s work is protected under copyright law as a compilation because—although the poems are not his work—he used his own tastes and judgment in compiling the material. The court further found that by publishing the work, Penguin had infringed Silverstein’s copyright and violated the Lanham Act by failing to attribute the work to him.

The court enjoined Penguin from selling or further distributing Complete Poems. As of this writing, the court has not determined damages.

Silverstein is seeking the cost of his legal fees as well as $150,000 in damages for each printing of the book. Silverstein and his lawyers claim there have been seven printings, but according to Dannay, the actual number and timing of printings is currently before the district court and has yet to be determined. Penguin filed an appeal on April 14.

For further updates on this case, visit www.pw.org/mag/industry.htm.

Suzanne Pettypiece is managing editor of Poets & Writers Magazine.