I’ve mostly had students reject trigger warnings.

Exactly. I’ve had the same experiences—students really dislike the idea of trigger warnings, as they should. Being surprised by a book is one of the good things about it.

I saw an interview you gave in late March that made me reflect again on The Satanic Verses and your experience there. You talked about how there is humor in all you do, something I was drawn to in all your work. And one of the things you discussed in the interview that moved me was that having the fatwa made people actually forget how funny The Satanic Verses is.

Yeah, nobody says it’s a funny book…except people who read it. But I think what happened is that it colored people’s expectations of what sort of writer they thought I was. And because it was such a dark event: In a way the characteristics of the attack were assumed to be also the characteristics of the writing. But that’s been a cloud that still hovers around me. I think for some people it gets in the way of picking up the book, like, “Oh no, that’s not my kind of thing,” because of assumptions made because of what happened.

And our names, I’ll bet. They see foreign names and think, “Oh, no, this must be some heavy thing.”

Yes, exactly. All I can do is continue to write. I mean, The Satanic Verses was my fifth published book, and this is my eighteenth. I certainly tell people not to read that book first—to read almost anything else first.

I found myself recommending to a student to read Joseph Anton first.

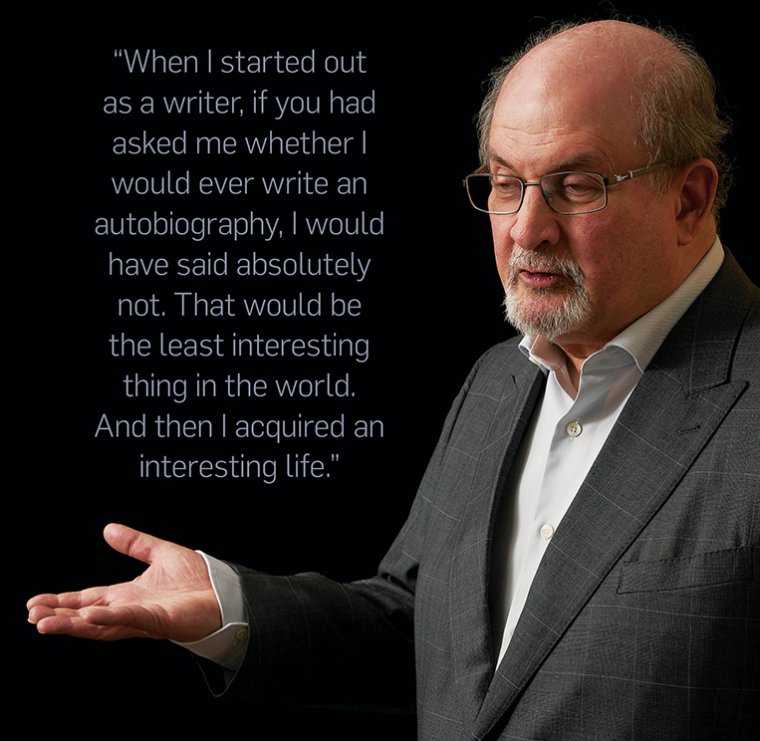

Well, I’m happy, obviously, but I just think of that as having done what I wanted it to do. When I started out as a writer, if you had asked me whether I would ever write an autobiography, I would have said absolutely not. That would be the least interesting thing in the world. And then I acquired an interesting life. Then I thought, “Given what happened, I don’t want somebody else to be the person telling that story,” so at some point I felt I had to do it. But still, I don’t think of myself as a nonfiction writer even though that’s the longest book I’ve written.

Do you have people read your work before it goes out?

Nobody sees anything until I’m finished. Then it goes here [to Andrew Wylie], and then it goes to the publishers. Then I do have a few friends I show it to, yeah. I really find it too frightening to reveal a work-in-progress. It’s so fragile. If I show you something and I know it’s not quite there yet and you say this is interesting and it’s not quite there yet, I get depressed. I mean once, years ago, when I was much younger, I went to a reading of John Irving’s in London in which he said this is a first draft and invited the audience to make suggestions. And I thought, “That’s so scary.” I could have never done that. So what I consider to be finished is where there’s a point at which I’m not really making it better anymore. I’m just pushing things around and making them different, and then I think, “Now I need to know what other people have to say.”

With all the many hats that you wear—humanitarian work, an appointment at NYU, the talks, the traveling—are you writing every day?

When I’m writing a novel, yes. The novel comes first and everything else has to take a number. I’ve always had this view that you wake up every day with a little nugget of creative juice for the day and you can either use it or you waste it. My view is, therefore, you write first. Get up, get out of bed, get to your desk, and work. Usually a couple of hours, until I know what I’m doing that day. Then I can go have a shower and the rest and then go back to it. Do the work first; otherwise it doesn’t get done. I’ve always thought of the novelist as a long-distance runner; that’s the marathon. It doesn’t mean a marathon runner is a more gifted athlete than a sprinter, but it’s just that kind of athletics. It’s long-form, you have to chip away at it, let the mark posts go by and trust that one day the finish line will come. You can’t even think about the finish line when you start.

I wonder if that’s why your work has a consistency to it that I feel. I can really see your project as an author. There’s a logic to it all.

That might be easier for you to see than me. Me, I don’t want to do the same thing every time. I’m always looking for some way to get at it in a way I haven’t done before. For example, the last novel came after Joseph Anton and was in many ways a reaction to it—because after this immense piece of nonfiction, I wanted to do something very, very fictional, something on the other end of the pendulum. And then I thought, “Well, that book goes as far into that as you could, so what else can I do that I haven’t done before?” And this kind of modernist way of approaching reality is where The Golden House came from. It came out of thinking about modernism.

I do think of you as a modernist author.

Well, if you think about it, modernism is a hundred years old. You know, modernism isn’t modern.

I love it so much. I tend to feel less aesthetically interested in a lot of what was categorized as postmodern.

I remember doing an event with Edward Said at Columbia, and in the Q&A this gentleman stood up who was clearly a member of the faculty—and he seemed very agitated—and he said, “We’ve always claimed you as postcolonialist; are you still with us?” And I said, “Well, you know, we just met!” I think the thing about postcolonialism is that, yes, obviously there was a period where it was very important, especially in India, and there is an obvious sense in which Midnight’s Children is postcolonialist. But it was seventy years ago. Nobody in India thinks very much about the British Empire. The subject is gone. So now you’re in a moment that’s post-postcolonial. I think the same thing is true for postmodernism. That we’ve gone a few steps more than that now—there isn’t a name for it, but there doesn’t need to be.

A modernist fan and writer friend of mine, Can Xue, calls her work neoclassical experimental instead of, say, avant-garde.

Well, I just don’t like labels. If someone tries to put me in a particular box, I immediately want to be in a different box. I’ve never been a great gang member. There are writers who like to travel in packs—I don’t like that. The thing about magical realism is, those guys really were thinking together in a way. They actually had a kind of project in the way the French surrealists had a project. But I have the Groucho Marx position: not wanting to be a member of any club that would have me as a member. I just think what is great about this art form is that it’s one single intelligence saying, “Here’s how I see it.” An intelligence that nobody owns. It’s just this one person saying, “I will tell you this.” And you can be lucky or unlucky—the point of that is it’s a big gamble. But the desire to be that individual voice I think is what makes a novelist. Every novelist I’ve ever loved has that thing where you know it’s them. You pick up a random page of DeLillo and it’s nobody else.

This reminds me of your reactions when people bring up the Nobel Prize. I’ve seen you laugh at the idea, though I personally think you should be up for it already.

But look at who gets it. [Laughter.] You know, I’ve been lucky with prizes a lot of the time, and unlucky a lot of the time, and that’s just the game. But I don’t think of it as serious.

You’re not perched by your phone on Nobel announcement day?

No. I mean, of course it’s nice when you win and it’s not so nice when you don’t, but I don’t really care. The thing that is much more of a prize to me is what we were saying earlier, which is that the books endure. If you are writing this kind of work, not pop fiction, the purpose is to write something that will endure, that hopefully will be around long after you’re not around. Martin Amis has this nice phrase that I always quote—what you want to do is leave behind a nice shelf of books. You know, Midnight’s Children is a really old book now—when I started writing it, it was 1976. The fact that it has managed to remain interesting to people two or three generations later, that’s a prize. Books survive only because people love them—there’s no other reason why a book survives ever. Books don’t survive because of scandal. If The Satanic Verses survives, it won’t be because of scandal. People forget scandal. Affection is the only thing that makes literature survive. That’s all there is.

Porochista Khakpour is the author of the novels Sons and Other Flammable Objects (Grove, 2007) and The Last Illusion (Bloomsbury, 2014) and the memoir Sick (Harper Perennial, 2018). Her writing has appeared in many sections of the New York Times, the Guardian, the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, Bookforum, Elle, Virginia Quarterly Review, and other publications around the world.

(Photo: Tony Gale)