Dan Chaon reveals more about what it’s like to live in our time than we may want to see. In his novels and short stories he creates for his readers a dark, skewed, uncanny world populated by characters who are like us and yet not like us. I’ve been a dedicated fan since I discovered the short story “Big Me” in Prize Stories 2001: The O. Henry Awards. I’ve eagerly devoured his novels—You Remind Me of Me (Ballantine Books, 2004) and Await Your Reply (Ballantine Books, 2009)—and his story collections, including Among the Missing (Ballantine Books, 2001), which was a finalist for the National Book Award, and Stay Awake (Ballantine Books, 2012). Chaon’s fiction has always felt to me like retreating into the kind of dream where familiar people appear with the faces of strangers, and places we’ve known all our lives are seen through an alternative lens.

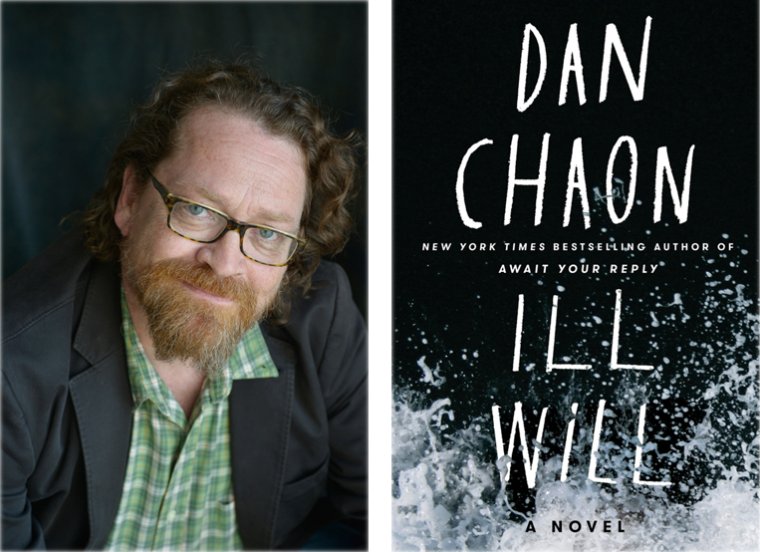

Dan Chaon, author of the novel Ill Will. (Credit: Ulf Andersen)

In this age of climate change and a reality-TV presidency, Chaon’s disquieting vision feels more real and more urgent than ever before. In his new novel, Ill Will, published this month by Ballantine Books, he tells us the story of a family beset by two crimes: the decades-old murder of Dustin Tillman’s parents, and, in present time, the mysterious deaths of college boys in and around Cleveland, Ohio. Dustin’s adopted brother Rusty was convicted of the family’s murder, but now that DNA evidence has resulted in the overturning of his conviction, Dustin must prepare himself for Rusty’s inevitable reappearance in his life. At the same time, his informal investigation of the disappearances of the college boys leads him to an increasing conviction that their deaths are linked. Ill Will is an innovative, unsettling, yet surprisingly funny novel by a writer who has spent a career holding a funhouse mirror up to America.

Dan Chaon teaches at Oberlin College and lives in Cleveland, Ohio. His fiction has appeared in Best American Short Stories, the Pushcart Prize Anthologies, and the O. Henry Prize Stories. He has been a finalist for the National Magazine Award in Fiction and the Shirley Jackson Award, and was the recipient of an Academy Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He was married to the author Sheila Schwartz, who died of ovarian cancer in 2008, and is the father of two sons.

At one moment in Ill Will, a character named Aaron asks himself: “What do you call that feeling where you’re certain that the world is doomed? It’s one of those feelings that’s physical, like low blood sugar or too much caffeine, a message from the lizard brain. But for a moment you know that it’s not just you. Not just Cleveland. It’s everything. We, the creatures of earth, are really and truly fucked.” One could describe all your work as having a certain darkness to it, but I guess this novel ended up being closer to the reality of the time than you expected

Well, one thing that was on my mind a lot, and has really sort of come to the forefront especially in the last six months, is the idea of Americans being willing to believe these very crazy things. Like the satanic ritual abuse hysteria—that was such a widely believed story [in the eighties], and now, looking back at it, it seems so crazy. But now we’ve seen the whole idea of truth fall apart in the last year or so, and even the concept of truth being called into question. That was something that I was very interested in and aware of while writing this book. I just didn’t want it to become such a big part of my real life.

You’re right that the whole idea of this post-truth world has been around for a while now. I was a kid in the eighties, and I remember the panic surrounding satanic cults, but it kind of disappeared from the public imagination for a while. Had you always had in mind as a subject for fiction? If not, how did it come back into your mind?

I had always been interested in trying to find a way to write about it, and certainly it fits in with a lot of other themes that I’m interested in. But it came up in a couple of bits of research I was doing about teenagers who went to prison during that period, and I was like, “Oh, yeah, this makes perfect sense for my character,” and I just sort of ran with it from there.

You’ve talked in other interviews about your writing routine, and in particular your habit of writing at night. You wouldn’t have to do that anymore, since your kids are grown up, but this feels like a book written at night. Are you still sticking to that schedule?

Well, it just turned out that I’d kind of built my life around that schedule. I should probably try to switch it up a little bit and become an early riser, but it’s comfortable for me. What it means is that I can get the practical work of the day done in the regular working hours and then allow myself to go partially into a dream world at night. And that’s an important part of the writing process for me, getting into this mode when you’re almost in a state of self-hypnosis.

Do you feel like you have more access to your subconscious in that state?

Yeah, I think so. Just having this chunk of uninterrupted time is super-important, when I know that there won’t be a knock on the door, no one expects you to answer e-mail at three in the morning. I tell my students, if they want to work for an hour, they need an hour to get into the right mindset, before they can even start. At least that’s true for me. If you take off for three days, it’s going to be three days before you can get fully back into a novel.

I’ve read a lot of interviews where you talk about fate, and the idea of fiction as a site for exploration of the different places that fate might take us. These characters, rather than choosing from different options, seem to be on a collision course with a kind of ironic fate, and there’s even a suggestion that Dennis, at the end of the book, might be repeating his father’s choices. Are these characters powerless in the face of their circumstances?

I think these particular characters may be powerless because of the various blinders that they have on and refuse to take off. There’s a line from the psychiatrist Lenore Terr that I think about a lot, where she says, “There are whole lives that are built around trying not to remember something.” And I think that’s such a fascinating idea. It makes perfect sense to me, that we would build our whole identities and our daily lives around trying not to think about things that are too troubling. So I think the characters who are more willing to face their darker selves and live with that are better armored than my main characters are.

There are a lot of similarities between Dustin’s life and yours. His wife, like yours, has died of cancer. You both have two grown sons; Dustin, like you, grew up in Nebraska and moved to Cleveland. Obviously this novel isn’t autobiographical, but you seem to be using more autobiographical material than in your previous work. Why?

It’s been eight years since Sheila died. Eight years is a long time, but in some ways it’s a short time in the grieving process. So grief has been on my mind a lot, and I wanted to write about it. At the same time, I didn’t want to write in the memoir form, and so finding a container that allowed me an outside, distant point of view and yet also to be able to write about it intimately was a powerful lure to me. So I definitely set up the chess pieces in a way that somewhat resembled my own life. I mean, it’s my house that they live in, as my sons were quick to point out. Although they also asked me to say in any interview that the sons in the book are not them.

I mean, this is one of the ways that writing can move us, and possibly provide this kind of therapeutic outlet. I’m not advocating writing as therapy, but I think that by traveling some of those paths in a fictional way, we can find a way out of the maze. I felt like this book did in some way help me out of that maze, even if it was a dark and painful journey.

And I imagine you had to wait for a time when you were prepared to talk about those things.

Yeah, some of those passages I never could have written without having some kind of form to put them in that wasn’t just my own autobiography.

I am surprised by how adept and present you are on social media. A lot of writers over forty are kind of grumpy about it. Is that something you enjoy?

Yeah, I do. I love my Tumblr page because it’s just a scrapbook, basically, and that’s my main social media outlet. And then my Tumblr posts to Twitter. I don’t really engage in political Twitter, but I love the community that talks about books and movies and is kind to one another. I really enjoy that.

You’re doing some interesting things with typography and the look of the page. How did you come to that decision? Do you see yourself moving in a more experimental direction in your work?

I’ve always been interested in typography and collage elements, but I never felt like I had permission to mess with them, because I wasn’t writing “that kind of book,” quote unquote. And then it just felt so right for this particular book and for this particular dreamy point of view. There were a lot of struggles with how to actually format it when it got to book form, but it really felt like it made sense and it wasn’t just experimenting for experimenting’s sake. One thing that brought me to the use of columns is an exercise that I have my students do. They have to make a table with six boxes, and they have to write a story with six scenes where each one can’t go over a page. I love what happened with that exercise, and how these tiny scenes talked to each other in this really interesting and complicated way, and you could move across the page in all these different ways. Then I started playing with it myself, because it seemed too fun to just give to the kids.

That’s some of the favorite writing I’ve done, and I’m really pleased with the way it turned out, even though I’m also worried about how it’s going to come across to readers. But I like it.

How did your editor react to this?

Well, we struggled with it, because once we started moving it into typesetting, it didn’t fit on the page in the right way, and so I had to do a huge amount of editing just to get it to fit the way I wanted it, so it lined up across and down. But we did manage and I’m really pleased with the result. We argued a lot about different elements, but it was a good kind of arguing, because she talked me out of some of the silly ideas that I had, and I talked her into some ideas that she was originally not down with, and then ultimately she was really helpful in guiding me through explaining why I needed to do it this way.

It’s a good time to be a writer who works the intersection between genre/literary, but you can also get pushback from editors and readers who might not know what to do with a novel that is betwixt and between. Has this ever been an issue for you?

It hasn’t been an issue for me yet. The one place where it is kind of an issue is in foreign sales, because in certain places like England, the categories are even more rigid than they are here, so to find a publisher who knows what to do with the book has been somewhat of a challenge. That being said, I had twenty different translations of Await Your Reply. So I’m hoping we’ll be able to figure it out. I do think that those distinctions are so random and so limiting that we have to break through them. And yes, there are readers who read only by category, but I don’t think there are that many.

This novel is a little bit tricky, though, because people who really like to consume serial killer books may be somewhat disappointed. I mean, it uses the formula, but it doesn’t have certain kind of satisfactions that, for instance, The Silence of the Lambs does.

Are you still writing short stories?

Well, I’m actually writing a TV pilot right now, a spec script for Ill Will. But then, yeah, hopefully a couple stories before I have to start another novel. I actually have four that I’m going to propose to my editor, and then we’ll see what happens. I think after hitting fifty, I’m starting to panic a little bit. I need to get busy.

How do you tell the difference between a short story idea and a novel idea?

It really does come to me later in the process. At least one of the chapters in this book was published originally as a short story. The part that takes place during Dustin’s childhood was published in Ploughshares with a different ending. And I’d originally thought that the part with the brother getting out of prison might be a short story. So there were pieces here that I worked on as short stories for a long time before I realized that they fit together as parts of something else.

So when they start lengthening and you start seeing connections between them—is that how a novel comes together for you?

I’ve always found that novels come together as collage for me. It’s, “okay, this piece fits here, and this piece fits here,” and so I’m always working with fragments to start out, and then it sort of builds into a whole. I’ve never had a novel come to me completely outlined and ready to go. I, in fact, did not know who the bad guy was in Ill Will until very late. Although now I go back and I can see that my subconscious was screaming at me though the whole thing.

I read an interview about Await Your Reply where you said that it was your wife who suggested the revelation at the end. I’d always assumed that the whole novel was built around that.

No, I went through a period of great despair in the middle where I thought, “I don’t know how to connect all these things, and I need to have something really amazing happen.” It took me forever to figure out a very simple solution. I think, like many writers, I get scared by something that seems like it might be corny, or it might be sentimental, or something that somebody rolls their eyes over, even while I forget that the things that give me the most pleasure are those very things. I mean, I love stories that have sentiment and I love stories that have action and surprises. I think this is part of our training as readers to say, “Oh, I’ve seen that before,” or “Oh, that’s corny,” and I have this part of myself that’s like a mean drunk at the bar, constantly berating me. You just have to shut that person up for a while, but it can be a struggle.

Do your students have a hard time taking that advice? I mean, I imagine that for kids that age, that’s a really hard thing to hear.

Yeah, but it’s also one of the things that gives you an insight into their process. I’ve had some kids who are amazing writers who just can’t get over that hump, and just get frozen with self-loathing when they can’t write a perfect sentence every time, or when the scene might seem a little off. And you know that those kids, as brilliant and talented as they are, aren’t going to get anywhere until they get over that. And then I have other kids who don’t have that kind of natural talent, but just have that determination to try, and revise, and do it again and again. And those are always the kids that become famous writers.

I saw that you made a list of your favorite songs of the year on Twitter, and you’ve talked in other interviews about listening to music while you write. Do you still? What music worked its way into this novel?

I did have a playlist. There’s this song by Modest Mouse called “Strangers to Ourselves,” and it has this kind of martial beat, and I can’t listen to it anymore because it’s basically the siren call of Ill Will. I also listened to a lot of Jennifer O’Connor, and The Mountain Goats. I listened to a lot of that really sad Sufjian Stevens album. Also there’s an old Doris Day song called “I’ll See You in My Dreams,” and that ended up becoming a really weird touchstone song as well.

Is there a particular part of the narrative that the music affects? Is it mood, or character, or sentence structure?

Well, maybe it’s me being part of a generation of people raised on TV, but it helps me to see the scene as if it’s a movie. Because I’m imagining the world, and this is the song that’s playing in the movie, and that really helps me picture the fictional landscape. It helps with the world-building that you do as you’re writing a scene. And that’s something that we do a lot, right, if you’re listening to a song? You’re taking parts of the mood and parts of the lyric that you can understand, and you’re creating a little music video in your head a lot of the time. So I feel like I just apply that music video to the characters and the world I’m writing about. But the first step is finding the right song.

My last question was going to be “What are you working on now?” but I guess we’ve already covered that.

Yeah, I’m working on these proposals that I’m super-excited about. I’m hoping to cover every genre before I die, so I have one that’s a Western, and one that’s fantasy, and one that’s a spy thriller. They might raise some eyebrows with my editor, but I’m excited about them.

Mary Stewart Atwell is the author of Wild Girls (Scribner, 2012). Her short fiction has appeared in Epoch and Alaska Quarterly Review, and in the anthologies Best New American Voices and Best American Mystery Stories. She teaches creative writing at Virginia Military Institute.