In October, twenty disabled artists were announced as the first class of Disability Futures Fellows and received grants of $50,000 each, to be used in whatever way is most useful in supporting their work. The new fellowships celebrate disability culture by honoring accomplished practitioners in a wide variety of fields, including writing, theater, dance, architecture, painting, and garment making. Developed by the Ford Foundation in partnership with the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the initiative is administered by United States Artists, a national arts funding organization in Chicago.

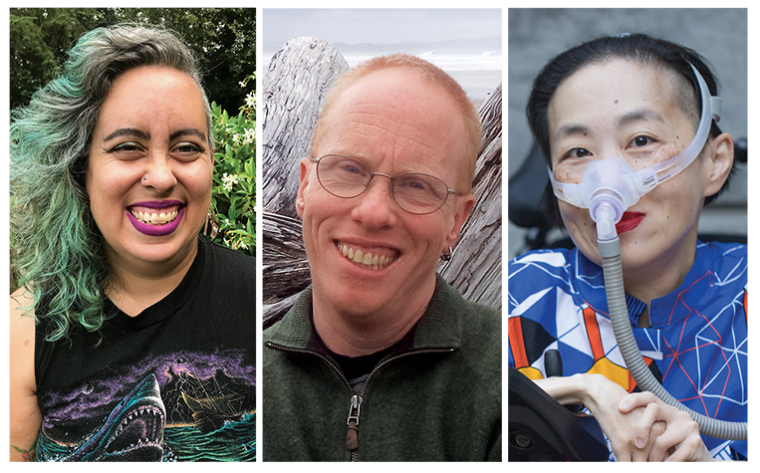

From left: Writers and 2020 Disability Futures fellows Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Eli Clare, and Alice Wong. (Credit: Piepzna-Samarasinha: Jesse Manuel Graves; Clare: Samuel Lurie; Wong: Eddie Hernandez Photography)

The awards are part of ongoing research conducted by, for, and with disabled practitioners to understand what they want and need from such fellowships, from accessible applications to flexible funds disbursal, because for many disabled artists a monetary award can too easily turn into a punishment. “I will die without my benefits; I get my health insurance through Medicare,” says fellow Riva Lehrer, a painter and the author of Golem Girl (One World, 2020). Full-time employment that offers health benefits can be difficult to maintain for many disabled people for whom hospital stays are more frequent, and eligibility for federal health care benefits is often affected by fluctuations in income. “People need to understand that if getting an award means that you lose your basic benefits and especially your health care, then you’re in much worse shape than otherwise,” says Lehrer.

“That’s something that we had to learn,” says Margaret Morton, director of the Creativity and Free Expression team of the Ford Foundation. “In that research and that work with disabled practitioners, we were able to gain a sense from their perspective of how they wanted to engage.” Individualized attention to the needs of each fellow is key, especially in terms of funds disbursal—some recipients opted to take their award over the course of several years to avoid jeopardizing life-supporting federal funds. The structure of the award is still being revised, and Morton believes it will continue on a two-year basis rather than an annual one.

As a blind writer I have noticed that it’s still quite rare to find disability mentioned in statements of diversity for grants, residencies, or literary journals. The Disability Futures award suggests that disability culture will become more overtly integral to arts and culture generally. Even if they have not been on the mainstream radar, “disabled, sick, Mad, neurodivergent and Deaf writers and artists aren’t new,” fellow Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha wrote in an e-mail. “We’ve been out here doing this work for a long time!” The author or coeditor of nine books, including Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories From the Transformative Justice Movement (AK Press, 2020), Piepzna-Samarasinha points out that for many people, disability is not about culture, but rather “deficiency,” which leads to situations wherein “you go to the bookstore and ask where the disabled section is and you get a blank stare and uncomfortable laughter.”

Ableism in the publishing industry can only be dismantled if people with disabilities are involved at every level of book creation. Disability activist, media maker, journalist, and Disability Futures fellow Alice Wong is one editor effecting this change. Of her work on Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories From the Twenty-First Century (Vintage, 2020), Wong writes: “It was a thrill and privilege to edit an anthology featuring thirty-seven pieces by disabled people who all have powerful and personal stories across different communities and fields. As a disabled editor, I intentionally curated these stories for us, by us and think of it like a Spotify playlist or mixtape from me to the disability community.”

Although the fellows are largely grateful for the award, some also voice misgivings. Eli Clare, author of Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling With Cure (Duke University Press, 2017), wrote in an e-mail: “As a white, disabled, genderqueer activist-poet, I dream of a world without police and prisons; without psych wards, group homes, and nursing homes; without capitalism and white supremacy. All of this leaves me unsettled about accepting money from private foundations that often have histories of supporting racism and eugenics and current funding practices that destabilize radical grassroots organizing.” As a result, Clare plans “to use and redistribute the money to create fierce survival, fierce beauty, fierce ugliness, and fierce dreams.”

No one can know what impact Disability Futures, the first major fellowship of its kind, will ultimately have. Disabled artists have occasionally won awards in the past, but not on this scale. “I think that the critical mass factor is key,” DeafBlind poet, essayist, and translator John Lee Clark wrote in an e-mail. “Now we have twenty disabled artists as the recipients of what is the rough equivalent of winning a Guggenheim. That is quite a message.”

The 2020 fellows reveal the wealth of talent in the disability community, as well as the diversity within it. Considering disabled Americans make up approximately 20 percent of the population, we cannot help but intersect with other often-marginalized identities. For fellow Jen Deerinwater, journalist, memoirist, and founder of the Crushing Colonialism collective, intersectionality is at the core of writing and activism. “Who I am cannot be separated out. Yes, I’m Indigenous. Yes, I’m Two Spirit, I’m disabled. But those things all go together. They don’t exist within silos.”

Deerinwater hopes that the Disability Futures award will “make other people in the arts go, ‘Hey, we need to start working with and listening to and taking direction from disabled and Deaf and ill creatives.’”

M. Leona Godin is a writer, a performer, and an educator who is blind. Her first book, There Plant Eyes: A Personal and Cultural History of Blindness, is forthcoming from Pantheon in summer 2021.