Diane Seuss calls her new book, Still Life With Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl, an “improvisational journey, unresolved.” While the journey may be unresolved, Seuss, who lives in Michigan and has taught at Kalamazoo College since 1988, is an expert guide, articulating the twists and turns—between high art and rural spaces, between brutality and joy—in exquisite detail. Seuss wrote two poetry collections, It Blows You Hollow (New Issues Press, 1998) and Wolf Lake, White Gown Blown Open (University of Massachusetts Press, 2010), before Four-Legged Girl, published by Graywolf Press in 2015, achieved a level of attention that was, according to Seuss, “unthinkably encouraging”: It was named a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry, which that year went to Gregory Pardlo for Digest (Four Way Books). Now, in Still Life With Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl, which has just been released by Graywolf, Seuss delivers a book that takes visual art as its primary subject—its title is from Rembrandt’s seventeenth-century painting—before branching off into poems that explore rural poverty, violence, memory, femininity, and the pleasures and problems of how we look at each other. The poems are subversive yet formally precise, meditative yet soaked in what Seuss might call “moondrool.” I recently spoke with Seuss about how the book came to be, her formative time at the Hedgebrook writing retreat, the relationship between poetry and the Internet, and more.

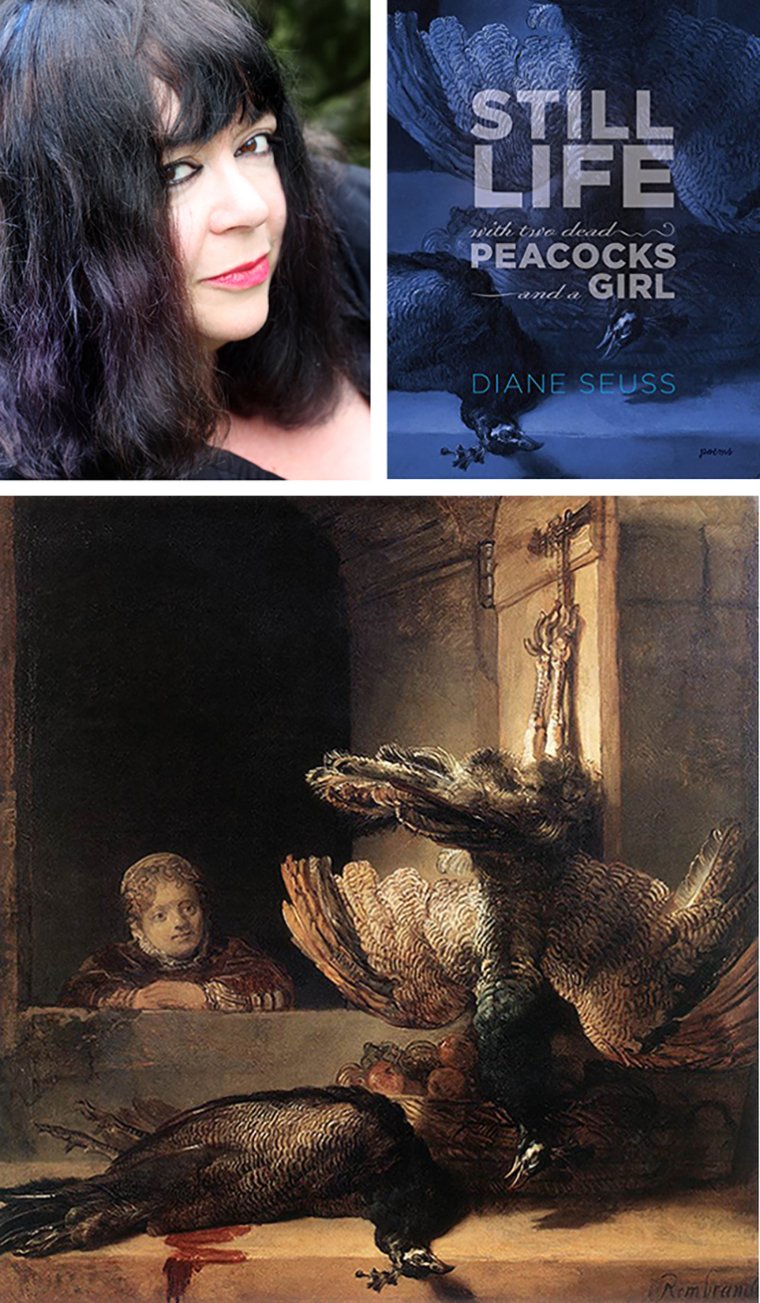

Diane Seuss, author of the new poetry collection Still Life With Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl, along with the painting by Rembrandt that inspired the title and cover. (Credit: Seuss: Gabrielle Montesanti)

From the first page, the reader understands that Still Life With Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl will be a book that engages with visual art. But it soon becomes clear that this is a book about class as well. One poem might meditate on a Rembrandt painting, the next on a Walmart parking lot. Can you talk about how these subjects intersect for you, and how they coexist in the collection?

I believe that the first poem I wrote for this collection was “Walmart Parking Lot.” Looking at it now, I see that it holds the DNA of the whole book. When I was in high school, my best friend, Mikel, and I used to save up to get a ticket on the South Shore Line from South Bend, Indiana, over the state line from Niles, to Chicago. We’d head straight to the Art Institute, and that’s where we’d spend the day. We had very little official information about art; our love for it was unschooled and shameless. We’d move from Caravaggio to Seurat to O’Keefe, lingering longest in front of Rothko, whose pulsing blobs of color represented our unspeakable desires, wishes we didn’t yet have words for. Our ride back at sunset took us through smokestacks and steel mills and finally to the cornfields and fruit stands of our town. Our yearning, which a yearning for art represented, seemed to be in direct conflict with our circumstances—rural poverty and low expectations and something akin to isolation. To pursue one was to abandon the other. This conundrum between the Eden of art and our lived experience outside its gates became the creation myth at the book’s center. I will add that when Mikel and I were growing up there was no Walmart. Kmart came late in the game and was shut down when Walmart built its superstore over a Native American burial ground. The small businesses went away, as did the one-of-a-kind truck stops and diners once the familiar fast food line-up took over US 31. It was interesting to me to conflate the cement rectangle of a Walmart parking lot that now characterizes so many small towns with fine art—to invite Pollack and Rothko and the rest in.

Thinking through that poem led me to researching early still-life painting, which represents a sort of link in my imagination between “low culture” and “high art.” Painters often considered still life—the painting of bowls and fruit, kitchen and dining room scenes, freshly slaughtered game, women’s work and women’s spaces—to be an opportunity for mere practice, certainly subject matter that did not contain the inspirational glory of historical and religious subjects. The parallels stacked up, between rural and urban, high subject matter and low, important people and everyday people, ideas and things. Poems of still life painting brought me to portraiture, especially those portraits in which women were the subject of the male gaze, and then to poems of self-portraiture. The book, I hope, is less an argument about art and rural spaces than a sort of improvisational journey, unresolved, between the two.

Your poem “Memory Fed Me Until It Didn’t” begins with the wonderful lines: “Then the erotic charge turned off like a light switch. / I think the last fire got peed on in that hotel outside Lansing. / Peed on and sizzled and then a welcome and lasting silence. // Then my eyes got hungry.” There is indeed a hunger to the poems in this book—a hunger to look outward and absorb the details of people, places, paintings. It strikes me as subversive that you tie this visual energy to redirected erotic energy. That’s already interesting. Then, in the very next poem, you further complicate the equation by introducing us to a male artist who uses his art as a way of deceiving. You write: “My whole life I’ve wanted to touch men / like Cornelius Norbertus Gijsbrechts, / but they will not let themselves be touched.” What is your sense of how gender and artmaking are interacting in these poems?

This is an astute observation. “Memory Fed Me Until It Didn’t” seems to track the end of not just the erotic charge but the memory of the erotic charge, and I guess I’d add a journey from being the subject of the gaze to what you call a new investment in visual energy, my own, as I turn back to the world. I placed the Gijsbrechts poem after that because I didn’t want the equation to be too neat nor the book’s trajectory too chronological. Gijsbrechts was a practitioner of trompe-l'œil—painting that deceived the eye with a profound realism. I find his work delightful and comic. He’s the kind of trickster figure with whom I often fell in love, a gaslighter who uses slipperiness to keep himself from risking too much. In a sense, this poem explores gendered interactions as a way of exploring the tricky relationship between the consumer of the painting or the poem and the painting or poem itself. The sentimental view of art is that it sustains connection, and sometimes it does. It also defies connection. The intimacies between art and onlooker can be—well—as illusory as those between lovers. As an art-maker, I consider myself as slippery as Gijsbrechts. At least I hope I am.

What was the process of writing this collection like for you?

I wrote the still life “sonnets”—the sequence of which the title poem is a part—after I woke from a very beautiful dream that I could not remember. I only knew that “still life” was written in the dark space behind my eyes, and that it seemed significant, so I started doing research and discovered Rembrandt’s painting “Still Life With Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl.” I was bowled over by that painting, which I imagined as a hungry girl on the outside, in the dark, leaning in to the picture plane seeking pie, not peacocks. Sustenance, not beauty. I invented a form for this sequence—fourteen lines, no meter or rhyme, but each line is seventeen syllables, what Ginsberg called the American Sentence. I then had the good fortune to spend some time at Hedgebrook, the residency for women writers on Whidbey Island in Puget Sound. This was after decades of teaching and single-parenting and still maintaining a writing practice. I entered Hedgebrook wide-eyed and exhausted.

Everything about Hedgebrook is exquisite, from the fields of lavender on the island to the view of Mt. Rainer to the thick forests to the surrounding ocean and the owls and ripe figs and the hollyhocks as big as my head. This privilege, of time, of literal sustenance—they feed you, wonderfully—brought me to the notion of Eden that frames the book. I was at once luxuriating in it all and aware that my people—my mother, my sister, my nieces, my son—would not have this opportunity. I was impaled on pleasure and shame.

I did much of the research for the poems there, reading books I brought with me, especially Norman Bryson’s magnificent Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life Painting. I found a magnifying glass in the cottage and spent a lot of time simply looking at paintings with it. I wrote much of the night, slept for a few hours in the early morning, walked and read during the early afternoons, took notes, sat in the silence, rested a bit after dinner, and then began writing into the night again. There was no media. No cell-phone service. I felt my feelings, grief and exhilaration and fear and something like sacredness, which came with the intensity of seeing. The last poem in the book is an allegory that arises out of my imagining leaving the island and returning home. The realization that comes in the last line was a surprise to me, and I cried. I don’t cry that often.

This book, despite taking early still-life painting as one of its main subjects, feels timely. You are investigating the dynamics of looking—and being looked at—and it occurs to me that the experience of looking has changed since you first began writing poems. In a previous interview with Columbia Poetry Review, you said: “The problem for me with the digital landscape is that all things bear equal weight, or appear to. The beheading is in balance with the Kardashian ass shot is in balance with the impending extinction of the polar bear is in balance with somebody’s baby bump.” What is your relationship to the Internet these days? Does it interact with your writing life?

Oh my. Well, I imbibe in the Internet. I love the fluidity it brings to research, and the way I can eavesdrop on a nostalgia page from a town I’ve never visited while reading the natural history of blue butterflies and learning that organic vinegar and turmeric can make me beautiful. The problem is, of course, it’s addictive, and we addicts are so easy to manipulate, and everyone reading this already knows it and yet there are kittens wearing top hats and sites where you can hear the earliest lullaby and people I will never meet telling me my profile picture is charming, which it is because: filters. I’m concerned, especially for younger poets, about the pressure to self-market, to become a social-media celebrity, when of course some of the best poets are terrible self-promoters and have no star power and therefore are no longer picked for the team. I was almost driven to violence when a tour guide at Emily Dickinson’s house stated that Dickinson would have been “a mad texter.”

I’m retro in that I believe the best conditions for writing include silence, solitude, and loneliness. Social media is loud, defies solitude, and provides a distraction for our loneliness. I’m fortunate to have grown up without it. Instead I wandered the halls of the hospital where my father was dying, played in the empty chicken coop, and had tea parties on the headstones at the cemetery next door. I have never gotten a worthy image from social media, but my mind could make milkweeds talk. I know that the Internet is changing our relationship to meaning-making, image, the line, and time. The notion that a poem can last is quickly becoming outmoded, but I guess I need to believe a poem has a life beyond the zombie eternity of the Internet. I am holding on to Williams’s “no ideas but in things” and cummings’s “Thingish with moondrool,” the concrete imbued with the imagination.

Carve that on my tomb; don’t type it onto my web page.

Of course, the Internet is not going away anytime soon, unless the power grid fails. It’s out of the box; there’s no stuffing it back in. One of my goals as a writer from a rural place is not to be nostalgic for “simpler times,” which they certainly were not. The past was no kinder than the present, and usually less so. I’m on board with all the arguments about the access the Internet affords. The activism. Screens are changing the way we see and where we look. How we inhabit our bodies. The nature of the imagination. Our relationship with the sentence. There’s no undoing it, so we must do it, until the next thing comes, and the no-thing after that.

Your third book, Four-Legged Girl, brought an increased level of attention to your poetry, in part because it was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. How did that feel, aside from exciting? Did it impact the way you approached writing afterwards?

To be heard is a lovely thing. To be heard and acknowledged is extraordinary and rare. To be honest, it was hard to take it in—I don’t think I was born with the receptors to know what to do with accolades. I don’t drink, but I had a couple shots of whiskey. In terms of my career, yes, there is more interest in my work, more visibility. Magazines solicit poems rather than my sending them out on a wing and a prayer, as I did for so many years, as most poets do. I was invited to give more readings and maybe assumed to speak with a degree of authority I wasn’t vested with before. This is all unthinkably encouraging. One feels that there are readers out there hoping to hear more—I wrote a letter to the world and it was answered. To balance those scales, I am still in the Midwest. I’m not coastal, urban, or young. Those elements work against celebrity—so my solitude is intact. A degree of recognition has made me a bit nervier, I think, a bit more willing to trust myself and what I tremblingly call my aesthetic. As I wrote in an earlier collection, I’ve not “been through the program.” I am largely self-taught. To experience the poetry world making space for me—well, it’s heartening, even as I remain marginal, and okay with my marginality.

Now when it comes to facing the blank page, all bets are off. It’s still between me and what Eliot called “a heap of broken images.” My responsibilities to language remain intact. My doubt stabilizes my audacity. At my best, my ambition is for my poems, not myself.

One of the quirks of the book publishing process is that, by the time your book comes out, you’re probably already working on a new one. What’s next for you?

Indeed, I am 108 pages into a new collection, though it will be hacked down into a more viable length even as I add new poems. It’s a collection of largely unrhymed sonnets which, strung together like paper dolls, will compose a kind of memoir, though as much a memoir of how we remember as it is a memoir of events. The poems gesture toward rhyme and meter now and then in order to recognize the sonnet’s history and its endless flexibility. I consider that form my closest ally, right now, like a picture frame the subject of the painting can reach through into the world. The working title right now is “Femme Fatale: Sonnets.”

Mikko Harvey is Poets & Writers’ Joseph F. McCrindle Foundation Online Editorial Fellow and the author of Unstable Neighbourhood Rabbit (House of Anansi, 2018).