Celebrated short story writer and poet Grace Paley died of cancer last August at the age of eighty-four. A lifelong activist, pacifist, and an early figure in the women’s rights movement in the 1960s, Paley was one of those writers who managed to combine a public life of frequent readings and appearances in support of a range of causes with work lauded for its artistic integrity. A familiar figure at writers conferences and rallies against, over the years, the war in Vietnam, nuclear proliferation, apartheid in South Africa, and the Iraq War, she was tireless in her efforts to bring injustice to light. As one of the first American writers to explore the lives of ordinary women in her work, she broke ground and served as a role model for women writers who came of age in the ‘60s and ’70s. In her writing and activism, she achieved something rare, a life in which the public persona and the private person were one.

Grace Paley was born in the Bronx on December 11, 1922, the daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants. Though she began her writing life as poet, she found the voice for which she would be known when she started writing fiction in her thirties, drawing heavily on her childhood in the Bronx and her experiences in her neighborhood in Greenwich Village. She published three volumes of short stories that established her as a master of the form: The Little Disturbances of Man (Doubleday, 1959); Enormous Changes at the Last Minute (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1974); and Later the Same Day (FSG, 1985). In 1994, FSG published her Collected Stories, which was a finalist for both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. She is also the author of a collection of essays, Just As I Thought (FSG, 1998) and a number of volumes of poetry, including Leaning Forward (Granite Press, 1985) and New and Collected Poems (Tillbury Press, 1991). This month, FSG will publish her final poetry collection, Fidelity, which she completed just before her death. Paley lived in Manhattan and Thetford Hill, Vermont. She taught at Sarah Lawrence College and the City College of New York. From 1986 to 1988, she was New York’s first State Author and from 2003 to 2007 served as the Poet Laureate of Vermont.

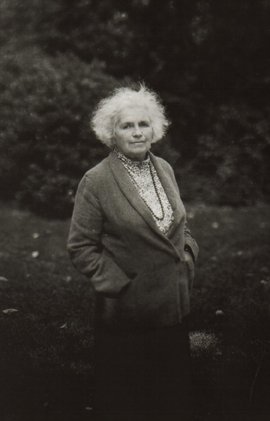

We interviewed Paley a little more than a year before her death at her home in Thetford. Arriving at the appointed time, we got no answer when we knocked on the door. We drove back down the steep dirt road to town and found her husband, Bob, in the yard of his son’s house. He asked if we had tried the door. It was unlocked, and Grace was there, taking a nap. “Go inside and wake her up,” he told us. We drove back up the hill and walked into the house and woke her up. She had been sick then for a year with the breast cancer that would take her life, but she entertained our questions with her characteristic wry humor and quick wit. In the last year of her life, Paley continued to give readings and to make public appearances when she could. She remained a vital presence and an inspiration.

Poets & Writers Magazine: You have spent much of your life protesting against war. How does it feel to be protesting again, with the war in Iraq?

GP: I never expected I would really change the world. I do a lot less protesting now because I’m not that well. But I can put it this way: I think the world is worse, but the people are better. I think this has to do with the revolutions of the 1960s and ’70s and the work we all did in that period. The important thing to remember about the Iraq war is that the whole world protested against it. For the first time in history, the whole world, not just me and my husband Bob, but the whole world came together to try to stop a war before it started. That had never happened before. I have a book with pictures of those protests from all over the world, from Africa, from Asia, from all over Europe. In every country people said, “No, no, don’t do it, don’t do it.” Whatever happens now, this fact is in the world. I think with those protests, we made maybe a couple of inches of progress. Some light flared there for a minute and that minute may be carried on. That’s why I say the world right now is a little worse, mostly because of what our country is doing, but the people are better because almost everywhere in the world there are people who are really thinking that they have some responsibility to make a peaceful world and to live decently. We’ll see what the next generation can do.

P&W: You have often said that you’re an optimistic person. How do you feel about social action? Are you still optimistic about the possibilities for creating social change?

GP: I’m optimistic because of that one moment when the whole world came out against the war. That has made me optimistic, but apart from that, I have a lot of anxiety about the state of the world. When you think of the things that have happened in Rwanda and Darfur, that are still happening in Darfur, it’s very discouraging. The degree of just plain murder is incredible. What’s happening in Iraq, where they’re all killing each other, is just terrifying. I’m neither optimistic nor pessimistic; I’m just on my knees hoping that things change somehow.

P&W: Do you think it’s important for writers to be socially active?

GP: Writers? I advocate plumbers should also do something, everybody should do something. When the Iraq war started, Sam Hamill from Copper Canyon Press got all these poets together. Before anybody said a word, he had ten thousand poets writing letters to the White House saying, “Don’t go into Iraq, don’t go in.” The writers were on top of it. I have no complaint about the writers. During the Vietnam War we had something called Angry Arts, which Bob and several other artists organized. For a whole week all the artists performing in concerts at Town Hall and Lincoln Center stopped and got up and turned their backs. Everybody was quiet for several minutes to make the statement we are against this war. Artists were making murals all over the city, and the poets were in trucks driving around reading poems. The artists were present. But everybody should be involved, not just the artists. Carpenters, teachers, everybody.

P&W: In one of your essays, you tell the story of when you went to Hanoi in 1969, and one of the young Vietnamese in the group was upset to hear the Americans criticize their country. He said, “Don’t you love your country? What about Jefferson and Emerson and Whitman?” What is it like for you to have difficulty loving your country and how have you handled this over the years?

GP: First of all, it was this dopey guy in our group of Americans who made these remarks. I can still see him saying, “Oh, you wouldn’t like to come to my country, it’s racist, you know.” And I thought I’d die. I wasn’t about to get up and say my country is not racist, but I thought, “You idiot.” Then this young fellow, this young Vietnamese man, comes and says, “Are you crazy, how can you talk about your country like that?” And then we did talk more about it. Well, I’m an American. I don’t feel national pride or anything like that, but on the other hand I’m very interested in this country. I’m very interested in the history of it, and I feel that it does have some valuable ideas that really have transformed many people. Certainly this is true when I think of my own parents coming here and all the other immigrants who have come here. They came for a reason, and they were satisfied, one way or the other.

My mother says she still remembers standing at the boat in 1905. The pogroms in Russia were terrible in 1904 and 1905. They started in the 1890s and they were terrible. The Jewish Forward had a piece about this a couple of years ago, looking back to 1905. They quoted from the accounts back in 1905 saying, “In the towns and in the villages, the slaughter has been immense.” So my parents came to this country. My father went to school immediately and learned Italian and English and became a doctor, and late in life became a painter, when he retired from being a doctor. My son said, “My grandfather is an artist retired from a doctor.” They did well. Not all immigrants have done equally well, but if you talk to Italians or Irish or Serbo-Croatians, the country welcomed them. Now we are unwelcoming to immigrants because they are a poor and undereducated class. The bad thing is these old time immigrants are not standing up enough for the newer immigrants—the Latino people who have been coming across the Mexican border and others. There are many different cultures in this country, which makes it a very interesting country.