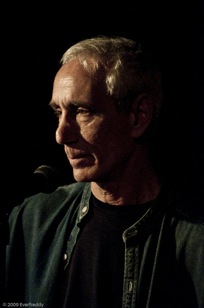

P&W–supported Larry Colker blogs about the triumphs and struggles of poetry workshops. He has cohosted the weekly Redondo Poets reading series for about fifteen years. In 2006 he won the California Writers Exchange Award, sponsored by Poets & Writers, Inc. His first book-length collection, Amnesia and Wings, was published by Tebot Bach in May 2013. By day Larry develops and delivers systems training for Kaiser Permanente. He lives in Burbank, California.

Billy Collins’s poem “Workshop” is a send-up of certain kinds of feedback and poems typically encountered in poetry workshops. As a veteran of dozens of workshops with many different leaders, and as the leader of a few, I both laugh at the parody and cringe for the targeted workshop attendees (myself among them). But I believe Collins is also implicitly implicating workshop leaders, who, after all, set the example.

Billy Collins’s poem “Workshop” is a send-up of certain kinds of feedback and poems typically encountered in poetry workshops. As a veteran of dozens of workshops with many different leaders, and as the leader of a few, I both laugh at the parody and cringe for the targeted workshop attendees (myself among them). But I believe Collins is also implicitly implicating workshop leaders, who, after all, set the example.

Why—and when—take a poem to a workshop? How to participate most effectively? How to lead a productive workshop? I have a few opinions to offer in this small space. Take them with as much salt as you wish.

Everyone assumes your poem is a draft. If you think a poem is finished and you just want acknowledgment of how good and finished it is and will be indignant at suggestions for changes (this is not unheard of), don't take it to a workshop. Likewise, don't bring it in if you honestly (secretly) think no else can appreciate your work! There's nothing wrong with having your own standards. But don't expect that others will relish being viewed as nincompoops.

The best participants (and leaders) ask themselves first: What can you tell about what the writer is trying to do from the piece itself? What strategies have been used and what choices have been made? Then: What is successful and what detracts? It is not unusual in regular workshops for poets to bring several reworkings of a poem back to the group. Familiarity with earlier versions is not necessarily useful. In the end the poem must work for readers who know nothing of its evolution. (However, those who have seen the difficult birth process of a marvelous poem do have a special kind of “midwife's” regard for the final product.)

Over time, one learns how to “do” a workshop as a participant. One picks up the etiquette. In most workshops that use the Iowa Writers' Workshop model, the author may not speak until discussion by the other participants and the leader is done—and the discussion is not directed toward the author. The author may ask questions after the discussion—about alternatives, for example—but explaining (defending) the poem is considered bad form. Take the feedback to your own counsel, where you can call certain comments misguided or idiotic, if you wish.

Leading a workshop is not a native skill either. And different experienced leaders settle on different approaches. But one of the most useful (and hard-earned) skills is referring to (or reading, or quoting) other poems that either illustrate a point of craft, or provide an example of a particular “maneuver,” or expand the writer's view of how a subject could be treated. I think that this both strengthens one's consciousness of belonging to a truly remarkable community and, frankly, raises humble awareness that one is not uniquely endowed in solving artistic problems in writing. But the satisfaction of solving those problems on my own terms—as the song says, “they can't take that away from me.”

Photo: Larry Colker. Credit: Fred Turko.

Major support for Readings/Workshops in California is provided by The James Irvine Foundation. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.