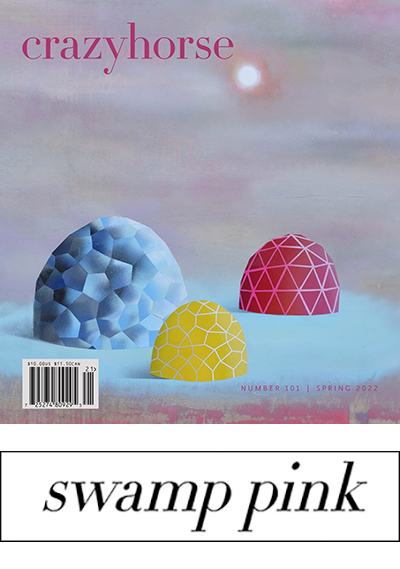

After more than sixty years in circulation, the literary journal Crazyhorse is poised to change its name to swamp pink, after a lily species that grows in the Carolinas. The Fall 2022 issue of the journal, published by the College of Charleston in South Carolina, will be the last under a name that the journal’s editors now recognize as a “longstanding appropriation of Lakota culture.”

The Fall 2022 issue of Crazyhorse will be the last under a name that the journal’s editors now recognize as a “longstanding appropriation of Lakota culture.” swamp pink’s editors pledge to go beyond rebranding.

Suzan Shown Harjo, a Cheyenne/Muscogee writer and activist who has worked for decades to eliminate commodified uses of Indigenous tribal names, sees the news as a positive development. “I am heartened that the journal is changing its name to something that is its own and in so doing is owning its half-century-plus of exploitation,” she says.

The name of Oglala Lakota leader Tasunke Witko is “commonly mistranslated as Crazy Horse,” says Harjo, who has received a Presidential Medal of Freedom for advocacy of Native issues. Popularly remembered as a warrior—including in the 1876 Battle of Greasy Grass, or Little Big Horn—Tasunke Witko was earlier “known among his people...as a mighty healer, a man of spirit so powerful that his horse was enchanted, magical,” says Harjo. The public distortion of his image is particularly disturbing since, according to Harjo, the leader “never wanted his photo taken, he never wanted to stand in front of the People.”

Yet Tasunke Witko has had his moniker and likeness misused many times. Hornell Brewing Company debuted Crazy Horse malt liquor in 1992. Its bottle featured an Indian in headdress, the phrase “PRODUCT OF AMERICA,” and this cloying copy: “A land where wailful winds whisper of Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and Custer.” Liz Claiborne featured a Crazy Horse brand of fashion; U.S. Repeating Arms Company, which manufactured Winchester-brand rifles, marketed a “Chief Crazy Horse Commemorative” rifle in 1983; and Neil Young’s rock band has used the name Crazy Horse.

What in the national mythology makes it seem permissible to mine and distort Native names, tribes, and icons? Stereotypes of the “noble savage” and the “vanishing Indian” feed widespread erasure of historical facts and contemporary indigeneity. Although sports teams have often defended their mascots and names by claiming to “honor” Native Americans, the National Congress of American Indians has called them “symbols of disrespect that degrade, mock, and harm Native people.”

The soon-to-be swamp pink also explains its original name as an attempt to honor the Oglala Lakota leader. Editor Tom McGrath—who founded the journal as Crazy Horse—admired Tasunke Witko, says current poetry editor Emily Rosko: “The belief, then, was that the literary work he published was akin to the rebellious spirit of Crazy Horse and his hero’s resistance to ongoing genocide.”

But Rosko has long felt troubled by a name she sees as “inappropriate, hurtful, unearned.” Shortly after she assumed her editorship in 2012, several writers from whom she solicited poetry declined to publish with the journal, citing its appropriated name. Thus began conversations with managing editor Jonathan Heinen about rebranding. The 2020 murder of George Floyd by a police officer and what Rosko calls a “national reckoning around racial inequality” moved the journal forward.

Nambé Pueblo scholar and educator Debbie Reese, who specializes in literary representations of Native Americans, finds literary institutions’ attempts to reckon with historical exploitation of Native culture important but flawed if they fail to better educate the public. “They must speak loudly and often so that those who read the journal can become aware of their own appropriations,” says Reese.

swamp pink will not be the first literary entity to have undergone a rebranding in light of a problematic relationship to Native culture. Squaw Valley Community of Writers altered its name to Community of Writers after objections to the offensive term “squaw,” and the organization asked for a sea change among constituents: “We recognize this name has a painful and derogatory legacy which has been disrespectful to the Native American community and goes against everything we stand for.... We hope you will join us and choose not to use the name in that context.”

swamp pink’s editors pledge to go beyond rebranding. The journal plans to rotate editors for what Heinen calls a “wider variety of viewpoints,” move to an online-only journal to increase accessibility, and launch an Indigenous writers contest in summer 2023 with external judges, cash prizes, and no entry fees.

These actions go some way toward addressing what for Lakota and other Indigenous peoples has been one more insult to stomach in a heedless and sometimes pointedly disrespectful literary world. But Harjo and Reese call on literary institutions to undertake more self-critique.

“Native Peoples are small in numbers today and cannot go to every offender in a population of hundreds or millions to entreat for respect for our ancestors and our coming generations,” says Harjo.

Kimberly Blaeser is the author of five poetry collections, including Copper Yearning (Holy Cow! Press, 2019). Wisconsin’s former poet laureate, Blaeser is an enrolled member of the White Earth Nation, an Anishinaabe activist, and an MFA faculty member at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe.