Poets Juliana Spahr and Stephanie Young—friends and colleagues at Mills College in Oakland, where they both teach—leaped into the seemingly unpoetic world of statistical analysis sixteen years ago. What began as an inquiry into gender parity in poetry publishing has expanded into a much more ambitious project, with a more complex and provocative question at its heart: “Who gets to be a writer?” Their search for an answer has led them and their former student Claire Grossman, now pursuing her PhD at Stanford University, to amass an enormous set of data tracking demographic and other information about nearly 1,800 writers over the past century.

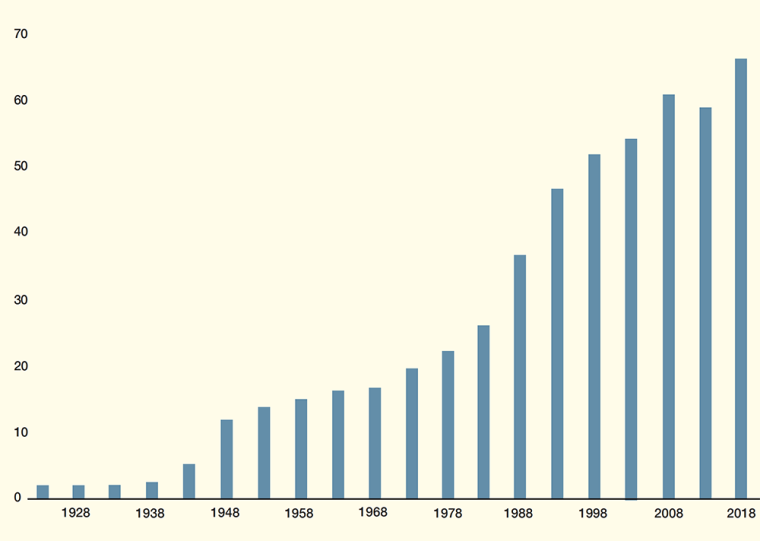

A graph based on data from Grossman, Spahr, and Young shows the growing number of major literary prizes offered in different genre categories, on a five-year average. (Credit: Adapted from a graph courtesy of Claire Grossman, Juliana Spahr, and Stephanie Young)

What these writers share is having won what Grossman, Spahr, and Young call a “major literary prize”: one of fifty U.S. national-level awards of at least $10,000 in poetry, fiction, or without genre specification. These honors include well-known prizes such as the National Book Award and lesser-known accolades, such as the Rosenthal Family Foundation Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. The Jackson Poetry Prize from Poets & Writers—founded in 2006 with a current value of $80,000—is also among those counted. Grossman, Spahr, and Young gathered information on more than 1,100 known judges of forty-one prizes as well. Their effort in tallying these numbers has been a matter both personal and professional, allowing them to satiate their personal curiosity while contributing to the scholarly discourse around literary production that is part of their work as academics. They aim to better understand the system of literary reward in the United States and who is represented in that system, which has far-reaching implications.

“We were thinking a lot about how higher education really shapes and frames pathways to becoming an artist of all kinds,” Young says. “And I think the prize began to emerge as one of those really increasingly powerful shaping mechanisms.” More than cash, a major literary award affords a writer attention, drawing a wider readership and professional opportunities, adds Young.

What she, Grossman, and Spahr have learned from their data is unsettling. The sphere of major literary prizes has ballooned in the period they studied: from one prize in 1918—the Pulitzer—to fifty named awards in 2020, with eighty possible annual prizewinners in different genre categories. Those winners have become much more diverse in terms of race and gender but they are ever more closely linked to elite educational and professional networks, or “the prestige apparatus,” as Grossman calls it.

The most crucial and enduring factor in that apparatus is elite education. By their calculations, about 40 percent of prize winners between 1918 and 2019 went to an Ivy League college—a percentage that has held steady for the past century, according to “Literature’s Vexed Democratization,” their 2021 article in American Literary History (ALH), a peer-reviewed journal published by Oxford University Press. Graduate degrees are increasingly common among the winners of major literary prizes, reaching 80 percent in recent years, according to the article, with half of MFA-holding winners attending one of a quartet of schools: Columbia University, New York University, University of California in Irvine, and the University of Iowa. The biggest player among these is Iowa, home of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, whose graduates are forty-nine times more likely to win a major literary prize compared with those of any other MFA program since 2000.

That last data point was published in “Who Gets to Be a Writer?,” which appeared in 2021 in Public Books, an online magazine that frames academic scholarship for a general audience. In that article, Grossman, Spahr, and Young object to the idea that their data merely “reflects excellence at work” in elite institutions, pointing out how socioeconomic disadvantages can be a barrier to entry for even great writers. “We think a lot about the student who went to Local State College prior to any of the 226 or so MFA programs other than Iowa,” they wrote, citing such students they have known. “Their writing is, if measured by all accounts that we understand, excellent. So it is heartbreaking to realize that the odds of being recognized by the literary establishment are stacked against them.”

For writers of color, the odds are further stacked, according to their article in ALH. Holding an elite degree, Grossman, Spahr, and Young contend, is much more important for nonwhite writers than white writers: While 55 percent of prizewinning writers of color in the twenty-first century hold an MFA, only 34 percent of their white counterparts do. For Black writers, the curve is even steeper: 60 percent of prizewinning Black writers hold an MFA, and they are far more likely to have an Ivy League degree than white prizewinners. Spahr, Young, and Grossman have described the situation by invoking Claudia Rankine’s statement in the New York Times in 2015 about Serena Williams: “The notable difference between Black excellence and white excellence is white excellence is achieved without having to battle racism.”

The reality of what amounts to a higher standard for writers of color, particularly Black writers, is important context to keep in mind when considering what are perhaps the most heartening of Grossman, Spahr, and Young’s findings: Their research states that about one-third of major literary prizes from 2000 to 2018 were won by writers who identified as other than white, roughly the same percentage of people who did in the 2010 U.S. census, according to their article in ALH. The gains for Black writers have been even more impressive: “In 2017, Black writers for the first time won more literary prizes, 38 percent, than writers of any other race or ethnicity,” Grossman, Young, and Spahr wrote in “Who Gets to Be a Writer?”

This suggests progress after a twentieth century in which writers of color “were not awarded major prizes with any consistency until the turn to multiculturalism in the 1990s,” Grossman, Spahr, and Young wrote in the ALH article. Yet literary production in the United States remains disproportionately white, according to their calculations in “Who Gets to Be a Writer?”: 90 percent of circulating titles in the twenty-first century are by white writers, a figure they came to after analyzing a sample from Books in Print, a database tracking all titles with ISBNs, including self-published books. Other studies that have excluded self-published books have found a similar preponderance of white authorship, including a 2020 report in the New York Times by McGill University professor Richard Jean So. In this light the literary prize may be seen as a veil draped over a still-exclusionary literary landscape, offering only “a limited, curated version of diversity,” the trio wrote in their ALH article.

All of these trends are more pronounced among poets. Not only are there more major literary prizes dedicated to poetry, but the monetary awards are more crucial due to poetry’s relatively small readership. In “On Poets and Prizes,” a 2020 article in the peer-reviewed ASAP/Journal, Grossman, Spahr, and Young likened the major literary prize for poetry to an “economy of favors.” While conceding that there is a fine line between mentorship and cronyism, they tracked a complex web of interconnection among poetry judges, prizewinners, teachers, and students—implicating some of the biggest names in contemporary poetry.

In December, a large portion of the raw data Grossman, Spahr, and Young have used in their analyses was made public—under the name “Index of Major Literary Prizes in the U.S.”—by the Post45 Data Collective at Emory University. Part of the growing field of digital humanities scholarship, the Post45 Data Collective houses peer-reviewed data for sharing among cultural scholars, aiming to “lay bare the mechanisms that maintain hierarchies across the arts,” as Dan Sinykin, an assistant professor at Emory and one of the collective’s editors, put it in a January article in the Los Angeles Review of Books.

The data that Grossman, Spahr, and Young published through the Post45 Data Collective was a smaller set than the one they have used to come up with their published findings on the changing demographics of prizewinners: While it lists individual prizewinning writers and judges by name, it does not list their racial identities, which they assessed by consulting self-identifications in author bios, inclusions in race-based anthologies, and other sources. Young said the decision to exclude racial identification from the data they sent to the collective stemmed from their reluctance to label named writers. “It feels really crucial for understanding the big picture,” Young says of having data on writers’ racial identities to report on broad trends, particularly given conversations about equity and inclusion that have swept the literary world. But “it didn’t really feel great to us to release something in which we once again were racializing people or to reinforce those categories,” Young says.

For the Post45 Data Collective, the decision to publish Grossman, Spahr, and Young’s data was focused on the set offered for publication: “The question for the Post45 Data Collective then became: Is this data set as submitted valuable—relevant and reusable—for post-1945 scholarship? For me and my coeditor, the answer was overwhelmingly yes,” Sinykin says. “Our judgment isn’t enough, though, peer review has to agree, and the peer review report came in overwhelmingly in support of publication.”

Richard Jean So, the McGill University professor who authored the New York Times report on the whiteness of fiction, was the editor of Grossman, Spahr, and Young’s “Who Gets to Be a Writer?” in his capacity as the digital humanities section editor of Public Books. So says he saw their data on race and found it to be “really credible and strong.” He points out that it is “not uncommon” for raw data to be withheld from public view even as scholars are publishing analyses of that data. So is also on the editorial board of the Post45 Data Collective, but he says he was not involved in the peer review of Grossman, Spahr, and Young’s data set; it was sent out for “blind” review by another scholar in the field, according to Sinykin. “I think the work that they’re doing is really important,” So says of Grossman, Spahr, and Young’s research, conceding that it is a “problematic exercise” to characterize writers by race, particularly for white scholars, in the case of Spahr and Young; Grossman does not identify as white. But the problematics are worth risking if the work “can lead to genuine insights about equity in the publishing industry that can lead to change,” says So, the author of Redlining Culture: A Data History of Racial Inequality and Postwar Fiction (Columbia University Press, 2020). “My hope is that their work is going to inspire more follow-up work by writers and scholars of color, people who will see the data and problem differently, and that will expand our perspective.”

Jen DeGregorio is an associate editor of Poets & Writers Magazine.