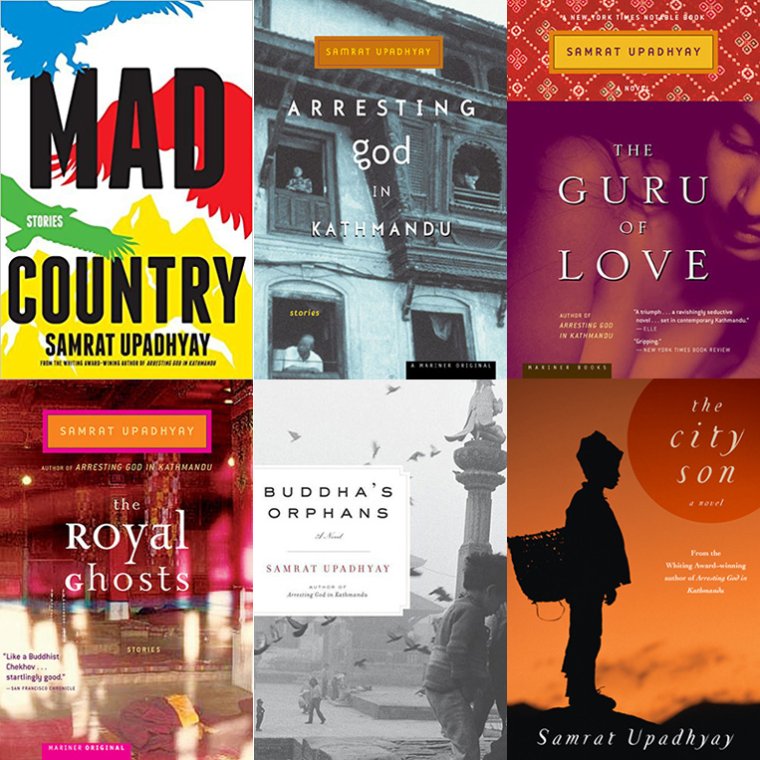

In his blurb on the cover of Arresting God in Kathmandu, Lee K. Abbott requested that you ought to be turned loose “to go hunting for God in the equally needy provinces of (your) new homeland.” Is Mad Country, at least in part, your reply or an attempt to do that?

If it is, it’s not a conscious one. I think the world has come much closer—through technology, social media, and so on—than when I was writing the stories for Arresting God in Kathmandu. When I visit Delhi, for example, I can go to a “lounge” and dance to the same Top 40 music that’s currently playing in the United States. My friends in Nepal carry the latest version of smartphones. So now it doesn’t seem unnatural that I’m writing stories that straddle both cultures, where concerns from one homeland seep into another.

Your first collection included stories that had been previously published. I noticed that The Royal Ghosts and Mad Country do not have any previous publications, however. How does that help or hinder the selection process and the composition that goes into finalizing a collection? What are the pros and cons of publishing a collection of completely unpublished short stories?

I didn’t expect my first book to be a story collection. I was doing my PhD at the University of Hawaii and publishing stories in literary journals. I’d heard and read that publishers didn’t want a story collection from an unknown author, so I was sending out my novels without luck. But once Arresting God in Kathmandu was published, I began thinking of story collections as books with an arc and thematic unity and stories within a collection speaking to and building upon one another. So, naturally, sending these stories out individually for publication took a backseat. The drawback to this could be that there is no validation of the individual stories through publication in journals, but my process has allowed me to focus on books single-mindedly.

You mentioned that City Son and especially Mad Country are somewhat experimental for you. Can you elaborate on this?

I have been a writer of realism, but with these two books I have played with the elasticity of both the novel form and the short story form to become slightly experimental. I have pushed images, sometimes to a degree of absurdity that I’m not used to. All in all, it’s been quite exciting.

From a writing method or craft perspective what did you do differently writing and completing Mad Country that you did not do for your previous story collections?

My initial draft of Mad Country had many more stories, a couple of them near novella-length. Some stories I excised myself; others I decided to cut after consulting with my editor Mark Doten at Soho Press so that we’d come out with a leaner and meaner book. I don’t recall having so many stories at my disposal with any of my previous collections.

When I hear the phrase “literature of exile” what comes to mind are writers who have been forced to leave a country or region because they are subverting the status quo there. But I think it goes deeper and transcends politics. These stories, and most of your work, pose a different, broader understanding of that phrase. Could speak to this theme of exile and reflect on how Mad Country embodies a “literature of exile.”

The modern definition of exile has expanded to embrace people who have experienced a loss of place. So, in this sense, my fiction often talks of people who have undergone displacement. Edward Said has written that “exiles cross borders, break barriers of thought and experience.” I have been particularly interested, lately and especially in Mad Country, in shifts in identities brought about by displacement. Some of my characters experience geographical exiles; others go through a kind of an internal displacement that challenges their notions of who they fundamentally are, everything they hold dear about their individual selves. There are several writers in whose work I find similar thoughts: Ha Jin, Nadine Gordimer, Amitav Ghosh.

Several main characters in Mad Country face either voluntary or forced exile. In some cases, characters experience a particular kind of madness relating to their situations. In “Beggar Boy,” Ramesh, a troubled young man who lives in his diplomat father’s mansion, attempts a Dickensian switch into the persona of a street urchin by donning the poor boy’s clothes. He indulges his imagination with robbery, suicide and quasi-psychoanalytic street scenes involving his father as a callous rich man passing he, a beggar on the street. Imagination and madness also collide in your novella “Dreaming of Ghana,” when an astonished Aakash finds that his dreams and reality begin to overlap even as political violence disrupts the fabric of society, culture and art.

For a few years now I have been fascinated by how porous and fluid our “self” is. The quality of our everyday experience, our perception and interpretation of the world, our emotional response to what happens to us—they are all dictated by this thing we call I. We are also very adept at creating as many different Is as needed to fit our experiences into certain molds. Our notions of home are also very much tied to our notions of who this self is. So, what happens when the home is displaced? What happens when the self turns into something else, or perhaps when the self goes mad? Looked at in this way, it seems like we are all experiencing madness in some way. Once this solid self is stripped away, we are all homeless, and thus, in a state of perpetual exile. In “Beggar Boy,” Ramesh begins to experience great disturbance within himself when he realizes the differences between the haves and the have-nots in his house and the city. When he allows his imagination to go on a mad spree he begins to bridge that gap, at least within his own mind, which gives him solace. Aakash in “Dreaming of Ghana” is disenchanted with his family life and the vapid articles he writes for the tourism magazine where he works. His imagination then propels him into a dream, which produces another reality that feels more substantial and satisfying.

In the title story, savvy and successful businesswoman Anamika Gurung is called away from an important business meeting because her teen son may be hauled off to jail from his school. The story follows the maddening conflicts Anamika encounters—those she causes and those she runs into—including both forced and voluntary exile. How do you see madness and exile at work in this story?

Anamika is filled with hubris regarding her station in life, drunk on the success and power she enjoys. But that all changes in one catastrophic moment when she’s exiled as a political prisoner in a world gone mad. At once she’s confronted with forces that sharply erode her notion of self, to the extent that her previous life of privilege start appearing crazy to her. Only after she’s forced to live, in her involuntary exile, among women who are clearly below her does she realize how flimsy, and irrational, her previous existence was. Kafka, who was a big influence on me early on, but whom I haven’t read in a while, probably was making his presence known in this story.

Race colors the madness in at least two of the stories, but in very different ways. In “Freak Street” Sofi from Ohio attempts to shed her identify by becoming Sukumari in her adopted Nepali family. Later, in the timely “America the Great Equalizer,” a Nepali student, Biks, runs smack into the turmoil of an American brand of racism on the streets of Ferguson. What would you like your readers to take away from these stories?

I believe in immersive experiences for the readers, so I’m hoping that they themselves will experience Sofi’s and Biks’s struggles with their racial and national identities. The older I get the more I am amazed at how similar we are despite our racial and ethnic backgrounds and our life experiences. Yet it’s also clear that many of us can’t seem to shake off our differences—and at times the differences seem entrenched and impossible. Both Sofi and Biks, in their exiles, realize how illogical the differences are between themselves and their adopted cultures, and yet, when given the chance to surmount these differences they are forced to reckon with obstacles that are both within and without. I am exploring whether our construction of race, and how we use it to discriminate and oppress, is dictated by our own ossified notions of self.