On the northern coast of the Hawai’ian island Maui, off a road leading down to the cliffs above the shore, a lush forest grows. Mango trees covered in vines stand next to palms as tall as eighty feet, while heliconia and hibiscus grow far beneath the canopy. Palm fronds and ferns wave in the air. The grounds are shady and quiet. And in the middle of the garden sits a two-story wooden house filled with books, the home of poet W. S. Merwin, who until his death at the age of ninety-one on March 15, tended to the thousands of palms and plants growing on the surrounding nineteen acres.

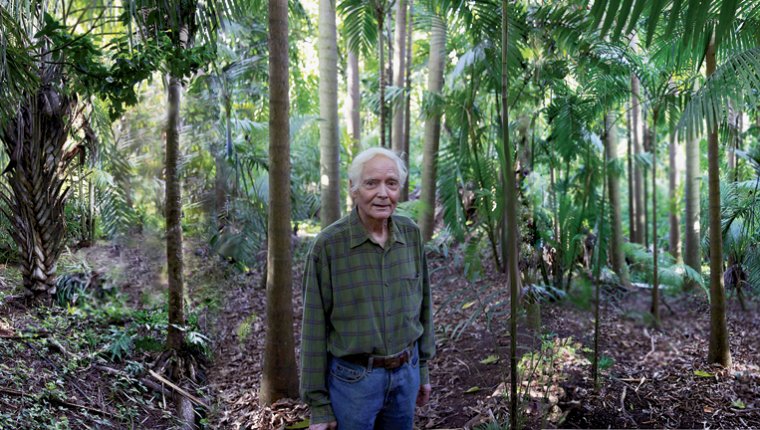

W. S. Merwin in the garden in 2010. (Credit: Tom Sewell)

Merwin lived in the garden, which includes one of the world’s finest collections of palms, for more than forty years. In December the Merwin Conservancy, which the poet and Paula Merwin, his wife, established in 2010 to protect the garden and encourage others to create their own artistic and ecological practice, will become the owners of the house and garden. “We are preparing to take on this kuleana—a Hawai’ian word that means responsibility but also implies incredible honor,” says Sonnet Kekilia Coggins, the conservancy’s executive director. “Merwin’s beloved garden was a product of his imagination and will be the site of inspiring and fostering imagination in others for years and years to come.”

Merwin acquired the land in 1977 after moving to Maui to study with the Zen Buddhist master Robert Aitken. He had already published and translated several books of poetry and won his first Pulitzer for his 1970 poetry collection, The Carrier of Ladders (Atheneum). When he purchased the property, previously part of a pineapple plantation, the soil had been ruined from years of farming. For the next four decades, the Merwins restored the land into the flourishing forest it is today, with more than four hundred taxonomic species of palms from all over the world.

Coaxing the soil back into health was not easy: Merwin planted something every day for a period of time, and his editor at Copper Canyon Press, Michael Wiegers, estimates he planted several thousand plants, many of which died in the first few years. Wiegers, who is also on the conservancy board, says the process of restoring the land parallels Merwin’s evolution as a poet. “Both poems and palm forestation seem very effortless, almost casual on the surface, yet both are very carefully considered, and earned over years of practice,” he says. “His first poems are lovely, but they also feel a little over-considered, just as when he first started planting on that land. Right away he wanted to reintroduce rare native species, but it didn’t work. He wasn’t able to force the plants to grow in dead soil. Through a daily life practice, he built and nurtured both the soil of the forest and the ground of his poems.”

Poems literally nourish the forest ground: Merwin would compost papers and correspondence—including the manuscripts sent to him by hopeful poets seeking a blurb—and add them to the soil. Coggins says she still comes across the notepads and pens he stashed around the garden in case he wanted to jot down a line. Until he lost his eyesight toward the end of his life, Merwin spent most of his days writing, meditating in the Zendo he built in the middle of the garden, and tending to the plants. “It is an enchantment, all of it, from the daydreaming to the digging, the heaving, the weeding and watching and watering, the heat, and the stirrings at the edges of the days,” he wrote in his book What Is a Garden? (University of South Carolina Press, 2016).

People cannot leave the grounds—muddy and full of mosquitoes as it is—without feeling changed, Coggins says. Poet Naomi Shihab Nye, a former board member of the conservancy, says, “Visiting always felt like stepping into another world. A deep, sacred, silent world, full of growing and chittering birds and timeless light and shadow.” Wiegers sees the garden as a work of land art, like Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field and Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, as well as a feat of conservation. In 2014 the Hawaiian Islands Land Trust recognized the ecological significance of the land by granting it permanent protection. Sara Tekula, the conservancy’s director of programs, says that palm experts and botanists who have visited the garden say that its palms come closest to the “fullest expression of their wild selves” of any cultivated specimens they have seen.

Merwin was known for his deep care and attention to the environment; his writing often expresses grief toward mankind’s role in destroying itself and the land, as well as reverence for the unknown and the natural world that connects all beings. Poet Jane Hirshfield says he was “a person whose recognition of the intimacy of all beings with one another was early and unparalleled.” By growing the palm forest, Merwin put into practice these values present in much of his work. “He didn’t hope for some change to happen elsewhere or by someone else’s hand or by some other force—he knew change was necessary, and he wanted to repair the whole legacy of human exceptionalism,” Coggins says. “So he went out and planted trees. It was agency; it was creative action.”

The conservancy’s work focuses on this idea of creative agency and integrity, or “walking your beliefs,” as Coggins says. She and the conservancy staff plan to launch a residency program in 2021 that brings artists, scientists, policy makers, designers—anyone with a creative practice—to Merwin’s home. The nonprofit already hosts school and artist visits and educational programs for teachers in the garden; publishes Merwin’s poems and information about the palms on its website; and runs a salon series, the Green Room, that brings thinkers and artists such as Richard Powers and Terry Tempest Williams to Maui and Oahu. The staff is also planning fund-raising events across the United States and a celebration in Maui in March 2020.

As the conservancy staff prepare to increase their programming when the garden passes into their hands later this year, Coggins admits it is bittersweet—Merwin was beloved by those close to him, as well as by many readers around the world. But his garden continues on as a living example of what one person can do to conserve the earth, even in the face of seemingly overwhelming environmental concerns—the quickening extinction of species, increased deforestation in many regions of the world, climate change—and the thorny geopolitics surrounding these issues. As he wrote in “Place,” a poem from his collection The Rain in the Trees, published by Knopf in 1988, “On the last day of the world / I would want to plant a tree.”

Dana Isokawa is the senior editor of Poets & Writers Magazine.