Poet, activist, editor, educator: One finds Tina Chang wearing as many hats in her daily life as there are layers of identity in her poetic work. Born in Oklahoma to Chinese immigrants, Chang was a year old when her family moved to New York City, not long after which she and her brother moved to Taiwan to live with relatives for two years. Perhaps it’s this early history that informs Chang’s idea of “the porous nature of boundaries—geographic, cultural, and metaphoric,” which she says has both evaded and invaded her imagination.

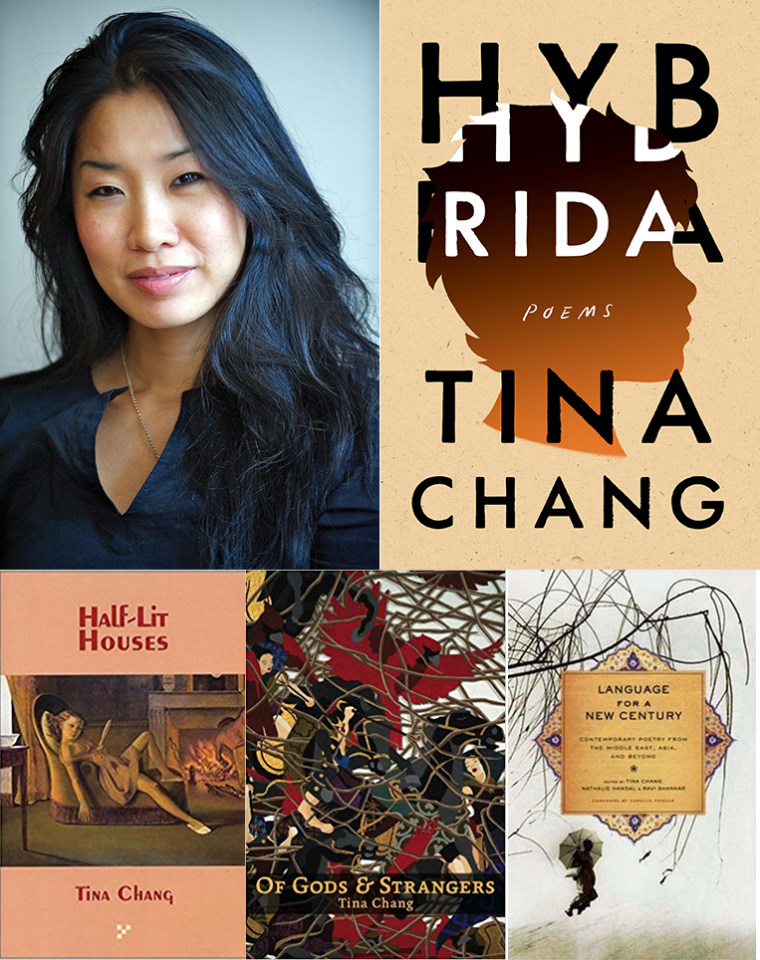

In addition to publishing two earlier collections, Half-Lit Houses (Four Way Books, 2004) and Of Gods & Strangers (Four Way Books, 2011), Chang coedited the anthology Language for a New Century: Contemporary Poetry From the Middle East, Asia, and Beyond (Norton, 2008), which poet Carolyn Forché described as “a field guide to the human condition in our time, a poetic survival manual.” As the poet laureate of Brooklyn, New York—she is the first woman to hold the post—Chang has organized initiatives for youth in underserved communities and events such as the New York City Poetry Rally against racial injustice. It’s no surprise that in 2017, Brooklyn Magazine named Chang one of the “100 Most Influential People in Brooklyn Culture.”

Chang’s new collection, Hybrida, published in May by Norton, may be her most resonant and timely project. Exploring concerns related to mothering a son with Haitian American heritage, positing hybridity as integral to the search for a new American lexicon, Hybrida has been described by Terrance Hayes as a “mature, masterful collection” that “mixes and remixes social and familial resonances; reconfigures forms, myths, and prophecies; and records the hybrid sounds of love.” I recently spoke with Chang about her artistic influences, her sense of history and mythology, and the poetic imagination in a fraught political moment.

While Hybrida explicitly engages the cultural zeitgeist, using various real-life incidents at the crossroads of race and gender, the reader notices a strong sense of elemental forces in this collection, particularly water. A grin becomes “a boat afloat at sea” in “Creation Myth,” “water teeters at the edge” in “She, As Painter,” and the speaker strikes down “white caps of longing” in “Prophecy,” among other examples. This creates an almost chthonic undercurrent to that frontline reportage, a tactile sense of storm and flood. How does this relate to the collection’s concerns about immigration, motherhood, and shifting identity? Was this imagery deployed as deliberate thematic commentary?

I’ve always been fascinated with water. When I was a young girl, I was afraid of drowning because I never learned to swim properly. It was only as an adult that I tried to master swimming. Most of my life, though, I watched water from afar, wondering and dreaming about it instead of swimming or floating in it. There was a longing to be immersed in something larger than me while feeling overwhelmed by its sheer force and power. Growing up, I was also fascinated by water in the Catholic tradition: holy water as a way of cleansing, renewing, and baptism. It marked a passage from unknowing to knowing and also something pure that was once stained. The Bible also offered water as a symbolic image: Jesus walking on water, God splitting the red sea, Noah’s Ark and the flood narrative. Taking in these stories as a young girl, my imagination was wild with its own interpretation of water, and my view of it had a lot to do with power, division, and immersion. I also saw it as an emotional image that conjured feelings of both calm and chaos.

Because it was such a flexible and inspiring force, I found myself returning to water often when I relied on myth as reportage. When speaking about identity, personhood, and motherhood felt overly direct and didn’t allow room for creative participation, I utilized mythological symbols such as water—and also its opposite, fire—to allow the images to pave the way for more expansive interpretation. Water is also a clear divider between two worlds: land and sea, tangible and intangible, reality and dream.

The middle of the book features a zuihitsu—a Japanese form and genre akin to the lyric essay that is sometimes translated as “running brush.” Your use of the form seems to lend itself to this sense of elemental immersion, as if these fragments of essay, reportage, and lyric emerge and submerge in a moving current. But as you note, it’s also a way of being indirect. Do you find poetry to be more effective artistically and/or politically when it employs strategies of indirectness?

Racial tension exists at the heart of Hybrida. It is difficult not to be completely direct when speaking about race because what we’re really talking about are matters of essential self, personal identity, and even safety. But I also wanted to address an open space of wonder, and perhaps that’s why I drew on myth and form. When I employed the zuihitsu form, I was letting go of aspects of poetic tradition that made me feel personally bound to Western, mostly white structures. I was influenced by Kimiko Hahn’s modern take on the zuihitsu. It’s an Eastern, female form and its freedom lies in fragmentation and even welcomed chaos. The embrace of intended disorganization felt right to me. After Trump was elected, I couldn’t embody polite neatness or any of the holy prescriptions I had so devotedly consumed in my youth. Growing up, I tried to do everything perfectly by attempting to write linear, tidy poems. I was no longer that person, and my poetic forms had to follow me wherever I wandered. I had to come to a meeting place with form and that was a place of struggle. I welcomed that.

Writing zuihitsu, I was able to approach difficult subjects from varied perspectives and modes of language. I’ve always been fascinated how the language used for news/reportage, lyric poems, essays, grocery lists is entirely different. We engage in this English language and shape-shift as we move from social media to conversation to journaling to letter writing. We are the same person moving through these mediums and yet our language finds different nuance. I hoped to write toward that elemental difference. I don’t know if that approach is effective, but it gave me a way to more clearly examine how we use words as political tools. For example, the reporting of Michael Brown’s death in a newspaper is very different from the language Lesley McSpadden, his mother, uses to describe the loss of her son. This to me was mother language, as far and as deep as the heart can reach. When I compressed these linguistic patterns together in the form of a zuihitsu, it revealed something about our present moment and the delicacy of words.

You’ve mentioned returning to the work of poets Jack Gilbert, Carolyn Forché, Nazim Hikmet, Agha Shahid Ali, and Federico García Lorca more than once. Is there a common denominator among these influences? Are there more recent influences? Hybrida’s use of ekphrasis reminded me of Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, and I wondered whether visual influences have become equally important.

Just the mere mention of these poets makes me pause. I greatly admire their work, their writing, their teaching, their humanitarian efforts, and their voices as they speak out against dominant political power structures. To function as a working poet is one thing. To live a life devoted to communal survival is another.

I recently took part in a discussion with local and national poets laureate in the United States. I would count all of them as people I admire who often place the community before themselves: Adrian Matejka, Vogue Robinson, Kealoha, Jeanetta Calhoun Mish, and Tracy K. Smith. Speaking to them, I came to understand we operate similarly. Many of us perform a job with long hours and no pay or office. So what keeps us going? I think we each see a life in the arts as not a luxury, but something essential to the lived experience.

As for the influence of Citizen, I greatly admire Rankine’s use of ekphrastic curation. I can read Citizen first as a picture book, gleaning so much from the visual imagery. I can interpret her choices of photography, sculpture, and video as a way to relay a sequenced story. When the text is introduced, it produces a wholly new experience, and that multiplicity of engagement with the material makes for a really moving experience. We can call the text lyric essays, prose poems, maybe poetic reportage. There is really so much to learn from Citizen, so much to discuss and continuously interpret. It’s a house where one door leads to another, then to another, and then I’m led to the wilderness.

In keeping with the zuihitsu, maybe I can see Hybrida as one long zuihitsu, a continuous dialogue that leads from one stage of conversation to another, which includes the visual image. It’s probably most apparent in the piece “4 Portraits,” where I engage with artwork by Kehinde Wiley, Alexandria Smith, Sondra Perry, and Kara Walker. When I approached these artists I admire about my project, they immediately said yes, which was a shock to me. Then I fought with myself over whether to include their artwork—since the visual images often employ the Black experience as subject matter and are created by Black artists, I was very conscious of the appropriation of images. I did not want to lay claim to a Black American experience as my own. I am Asian American and my husband is Haitian American; my son is biracial and I spoke as a mother to his experience and our communal experience as a family. I was eventually able to include the artwork as a conversation of maternal hope and protection. As I state in the zuihitsu, that mother language is a valid and ancient one.

This year is being celebrated as the bicentennial of Walt Whitman’s birth. Particularly in your role as poet laureate of Brooklyn, how do you relate to someone like Whitman, who is often a problematic figure? (In a well-known case at Northwestern University, a student refused to perform a musical interpretation of Whitman on the basis of his racial views.)

I’ll be the first to say that Whitman’s views on race are extremely problematic. It’s hard to excuse his remarks toward and about Native American, Black, and Asian communities. In this light, it has been hard for me to embrace him wholeheartedly. In recent poetry projects I have specifically invited a diverse set of readers to reinterpret his work. When they recite lines from “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” they present a new way of looking at his lines. Although it’s difficult to divorce the work from the writer, I have found that when I hear his longer work in a contemporary light, through contemporary voices from vast and wide backgrounds, I can view his words through the vessel of these beautiful bodies. It’s a new world that requires new interpretation. I can read these lines through a different filter, “What is it then between us? / What is the count of the scores or hundreds of years between us?”

In Hybrida, the inclusion of artwork by your son, Roman, is such a bracing and radical turn. It’s a powerful gesture in terms of voice and who is given a platform to speak. Could you talk about this decision? Do you feel our political moment demands an assumed autobiographical “I” in poetry? How does that relate to one’s claim to narrative?

I’d like to answer the second part of your question first. The autobiographical “I” has always been controversial. By claiming an “I” as fully autobiographical, the poet gives up a landscape of invention and imagination. Although Hybrida claims Roman, my son, as inspiration, there are also wild meanderings, dreamscapes, and myths where his presence is placed at the very center of entirely conjured worlds. I have freedom to work with material when I release the autobiographical “I.” The current political moment requires that we speak the truth as much as we can, but truth can be relayed in many ways. We have already seen truth twisted, shaped, and contorted to fit a political agenda. Poetry works against this because poetry has no true agenda. If poetry were to write to an agenda, it would no longer be poetry. I think it would take a different form.

Hybrida ends with a drawing and poem by my son, Roman. This, too, is an act of invention. His poem was an excerpt of a longer science fiction story in which a boy imagines the end of the world—a common theme among ten-year-old boys, it seems. In his story, the main character is a superhero who can walk into rooms and peel off his skin; he then seamlessly blends into the world. What does this action mean? I found the question he included in his drawing, the question “Who Am I?”, to be so significant. Because I was writing Hybrida mainly from the voice of a mother, it seemed essential to end on the son’s voice, a claim to power—as if the son was rearranging history to take the moment back and say, “Let me speak for myself, Mom.” I wanted his voice to end the book, the resting place where all the difficulty, questions, and possibility sided with him.

What’s next for you?

There’s a space that a previous book leaves, and I’m living in that space now. I have poems I’m still writing for Hybrida, but I have to let them hover in my imagination now. Moving forward, I’ve been taking notes for children’s books I’d like to write. I have many ideas, and I think one of them will stick soon. I also have plans for a young-adult novel-in-verse. I’ve been fascinated with the genre for a long time. I think both projects will lift off the ground as the summer leaves me more time to dream of them. My children serve as inspiration for all the projects I’ve named.

Jerome Ellison Murphy is the undergraduate programs manager of the NYU creative writing program and has served on the board of Lambda Literary. His critical writing has appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Publishers Weekly, the Brooklyn Rail, Lambda Literary Review, and American Poets, while his poetry appears in Narrative, Literary Hub, the Awl, and Radiolab. Visit him at jemwords.com.