At the beginning of 2017, I moved to Toronto from Chicago, watched Trump’s inauguration online with the same shock and dismay as everyone I knew, and opened the first book of In Search of Lost Time, Marcel Proust’s seven-volume journey into memory, love, and La Belle Époque.

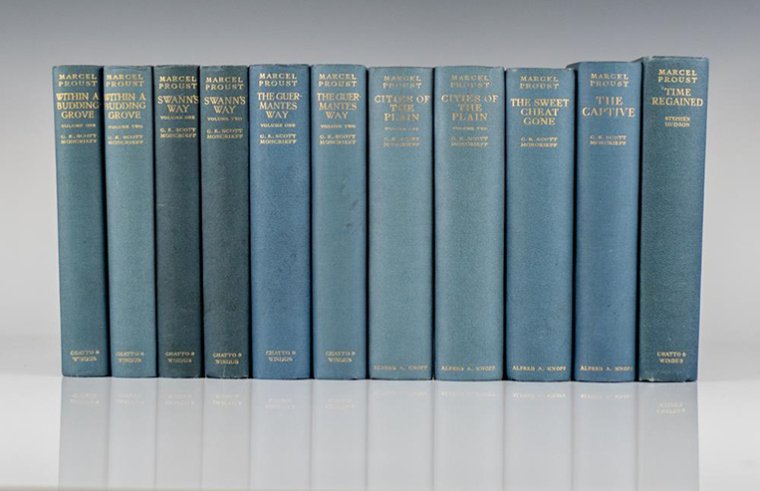

A first edition of In Search of Lost Time (Remembrance of Things Past) by Marcel Proust, translated by C. K. Scott Moncrieff, published by Chatto & Windus and Knopf in 1922. (Credit: Raptis Rare Books)

In a year of unreason and incivility, the challenge set by my friends to finish the book seemed like an antidote: full immersion in a great work of literature, an anxiety-free trip down a lane in France. Maybe it was an escape, a flight from my feeling of helplessness. But once a president whose sneering contempt of reflection and knowledge entered the White House, it felt like there was something political about every reading choice I made. I told myself, “I’ll read. That’s what I can do.”

It’s not just the sheer length of the books that drives people away. A sentence of Proust might take a page or longer, the subject and verb far distant in a long swimming sea of side thoughts and lush adjectives piling at your feet. The glitter, the glamour, the exacting eye for detail that Proust is known for is on exhausting display on every page. So is the nearly pathological obsession. Consider the first sentence of volume 2:

My mother, when it was a question of our having M. Norpois to dinner for the first time, having expressed her regret that Professor Cottard was away from home and that she herself had quite ceased to see anything of Swann, since either of these might have helped to entertain the ex-ambassador, my father replied that so eminent a guest, so distinguished a man of science as Cottard could never be out of place at a dinner-table, but that Swann, with his ostentation, his habit of crying aloud from the house-tops the name of everyone he knew, however slightly, was a vulgar show-off whom the Marquis de Norpois would be sure to dismiss as — to use his own epithet — a “pestilent” fellow.

There is Proust’s mind on display in that frenetic, yet languid unspooling of information, the obsessive analysis of human sociability. The books have the hallucinatory quality of a long night in Paris—trailing from one party to the next until the sun rises. And how many readers would keep reading through volume after volume? The quest for that mysterious last sentence kept me going through all of 2017, reading a little every day, counting the pages and doing the long division, parceling out the world of Belle Epoque Paris.

Proust would provide a framework for my entire year. The year I got married. The year I sold my first novel, The Devoted, and confronted the sometimes terrifying hypothesis that people might read my work and that my most private emotional life—the life I’d poured into my novel—might become a subject for public dissection. And, yes, the first year of the Trump presidency. On a day when the news on the Internet was depressing, bleak, or unspeakably awful, I opened the book and felt a quietness return to my mind instead of panic and emptiness. The agitation, anger, and fear of skimming through the day’s news gave way to the gold-hued light of a Parisian drawing room, or the slow swirl of crumbs from a madeleine in a cup of lavender-scented tea.

![]()

Volume 1: Swann’s Way. Trump is inaugurated; I move to Toronto to start a new job and look regretfully over my shoulder, considering what uneasy exile I’ve chosen. Proust is living in exile too—but the exiled country is his childhood, and the border the inevitable march of time:

It was a very long time ago, too, that my my father ceased to be able to say to Mama: ‘Go with the boy.’ The possibility of such hours will never be reborn for me. But for a little while now, I have begun to hear again very clearly, if I take care to listen, the sobs that I was strong enough to contain in front of my father and that broke out only when I found myself alone again with Mama. They have never really stopped; and it is only because life is now becoming quieter around me that I can hear them again.

Every now and then, we return to our land of exile; Proust’s jump into the world of memory is the subject of all seven volumes of his story. I return to America, too, for short weekend visits. I’m both ecstatic and uneasy, wondering if I have less of a claim on my home, if it’s no longer mine.

Volume 2: In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower. On Good Friday my novel sells. I feel a dizzy euphoria coupled immediately with strangeness; this day that I’ve worked towards for so many years can’t really be here, it doesn’t make sense. In Proust, the narrator is discovering the dizzying joy of books: “A well-read man will at once begin to yawn with boredom when one speaks to him of a new ‘good book’, because he imagines a sort of composite of all the good books that he has read, whereas a good book is something special, something unforeseeable, and is made up not of the sum of all previous masterpieces but of something which the most thorough assimilation of every one of them would not enable him to discover, since it exists not in their sum but beyond it.”

I’m comforted by his cultish devotion to words and art; there are other readers out there who are deeply moved by art, who dream of it all the time, even if it threatens to subsume their lives. Proust says, “If a little day-dreaming is dangerous, the cure for it is not to dream less but to dream more, to dream all the time.”

Volume 3: The Guermantes Way. In the summer I get married. I remember waking in the morning and feeling the quiet of it: a bird singing, the day and its busy excitement ahead, my whole body still and relaxed in my sister’s guest-room bed, ready.

For Proust, love is an intense experience of the sensual, an explosion of both the pain and pleasure of being alive. All love is also self-love. He writes, “When we are in love, our love is too big a thing for us to be able altogether to contain it within ourselves. It radiates towards the loved one, finds there a surface which arrests it, forcing it to return to its starting-point, and it is this repercussion of our own feeling which we call the other’s feelings and which charms us more then than on its outward journey because we do not recognise it as having originated in ourselves.” For Proust, love is a mirror; we love the vision of ourselves that we see in the other. When I look at my new husband during the ceremony, he has the same solemn smile that I know is on my face.

I’m thinking as I read that writing a novel is like falling in love: We throw everything we have, all the best of our lives, into the story, and later, we see the egotism of our own petty thoughts and imaginings staring back at us. In my own novel I take the narrative of my life and tweak it, consider the what-if’s of another path I could have taken. I’ve had to grow up a little to understand who I was as a child. I’ve changed myself to better fit the story I’m writing.

Still reading volume 3, I spend my honeymoon in Japan, where I watch headshots of Anthony Scaramucci appear beside katakana captions on a hotel television. I’m struck by the elaborate and absurd tune of the politics we’ve been forced to dance to this year. Proust’s third volume is an ode to and a critique of French aristocracy, an awed examination of the great families of France’s struggles to stay on top of a crumbling social hierarchy. Who are these absurd actors, really? What’s beneath the ivory masks? Proust writes, “People do not, as I had imagined, present themselves to us clearly and in fixity with their merits, their defects, their plans, their intentions in regard to ourselves (like a garden viewed through railings with all its flower-beds on display), but as a shadow we can never penetrate, of which there can be no direct knowledge.”

Plans within plans, secret machinations, all in the guise of beauty and order: dinners and salons and weddings, walks in the Jardin de Luxembourg, invitations and cards left carefully by the door. Secret meetings, Russian aides, missing e-mails, tax returns, faulty memories, lies and deceit.

Proust presents his characters’ anti-Semitism and racism to us as evidence of their inner corruption. But In Search of Lost Time has an unmistakable affection for the flawed world it portrays. Its high class characters are rarefied, ridiculous, and charmingly, fumblingly human. For all its frustrations, I’m falling in love with this book, the way anyone you live alongside and commit to truly knowing can become beloved.

Volume 4, Sodom and Gomorrah. In the fall I go to work teaching American short stories to Canadian undergrads, and I read about the active and thriving gay community in Belle Epoque Paris. Proust portrays its rulers, its queens, its freely transgressing lesbians with compassion, humor, and sympathy. He does not shy away from their suffering, and the crisis of identity that follows a class of people condemned by church and king and family. When he refers to the “race” of the homosexual, he writes mournfully that it is “a race on which a malediction weighs and which must live in falsehood and in perjury, because it knows that its desire, which, for every created being, is life’s sweetest pleasure, is held to be punishable and shameful, to be inadmissible…sons without a mother, to whom they are obliged to lie even in the hour when they close her eyes.” The narrator is drawn to the beauty and freedom and the hidden pain of the other side of the city, the culture rarely acknowledged but always present, shaping alliances in unspoken ways.

Volumes 5 and 6, The Captive and The Fugitive. It’s already October, and I’ve got three volumes to go. The Mueller investigation is heating up; my novel has a cover; I’m no longer allowed to make changes to my manuscript. Proust’s narrative thread is fraying so thin that I lose track of what party I’m attending, whose foppish spouse and whose clandestine lover is whose. Time is both fluid and crystalline, a drill diving back into the exact memories of childhood, or a watery treading through long late-night conversations. Marcel is deeply in love with the feisty, intractable Albertine, but Albertine has a lively love life of her own, with servant girls and female friends. Her sexual freedom, the easy way she travels through her world on a floating thread of desire, is revelatory to me and maddening to Marcel.

Then in one cruel sentence, Proust dispatches a crucial character, someone I’ve grown to love. I’m shocked; I want to throw the book across the room, surely it couldn’t end this way. I’d been fooled by Proust’s beauty into thinking this was a love story, but it’s really more about loss. Proust had to make me fall in love to feel the grief of dissolution. Life is felt most deeply when it’s slipping away from our baffled fingers.

Volume 7, Time Regained. In December my husband and I get a tiny apartment-sized tree and decorate it with the few ornaments we’ve acquired in life: a crocheted donut, a palm tree from relatives in California, a Frank Lloyd Wright art deco piece picked up in Chicago. Holidays are such delicate times. I lost my mother to cancer five years ago and now every small marker on the calendar (another Mother’s Day, birthday, Christmas without her) bears tragedy with it. In his final volume, Proust writes of World War I’s arrival in France. When the troops march into Paris and fill every hotel and bar, we see the loss of the liberties of the Belle Epoque. In this jingoistic time, prominent gay characters, once the toast of the town, are now subversives. All the depth and liveliness of Proust’s world has been hammered flat. Marcel’s journey into time is hazardous, he notes, because the journey reminds us of how utterly gone the past really is to us, like a lost lover or mother or friend. It cannot ever return.

My family plans to spend a few days in Paris at the end of the year. My husband’s and my plane is delayed by snow, and then cancelled, and I’m forced to spend Christmas holed up in a hotel in Montreal. It’s the first Christmas I’ve ever spent away from my family; even though it’s childish, I sob in my husband’s arms.

I picture Proust holed up in his 9th arrondisement apartment, often bedridden, almost always housebound, writing In Search of Lost Time in the final years of his too-short life. Mourning a world already lost to him even as he struggled to rejuvenate it on his page.

In Paris, there are few sites of pilgrimage for Proust fans. There’s a plaque here and there across the city, I’ve read online, only modest markers of places he visited. And of course, there’s his grave, in the famous Pere Lachaise cemetery on the outskirts of the city. I decide not to see it. I’ve never been the kind to seek out physical monuments; the writing is the monument, my year immersed in slow reading the reward. I’m happier imagining Marcel on his journey through time and memory. And he has warned against such trips anyway: “Such pilgrimages are extremely hazardous and they end as often in disappointment as in success. Those fixed places, which exist along with the changing years, are best discovered in ourselves.”

With just a week left in the year, back in Toronto, I finished the last volume, Time Regained, and closed the book. I won’t spoil the final moments for you; it’s there, waiting, if you want to read it. My apartment was quiet; my husband fiddling with his ukulele in the next room, letting a chord fall into the space between us. The year drawing to a close, all the surprises and joys and little tragedies now in the past. A sense of sadness passed over me, and then loss—the kind of feelings that remind you you are alive.

Blair Hurley is the author of the novel The Devoted, published in August by W. W. Norton. She is a Pushcart Prize winner whose work has appeared in West Branch and Mid-American Review, among other publications. A native of Boston, Hurley now lives in Toronto, where she teaches creative writing at the University of Toronto.