In the fall of 2017, Erica Vital-Lazare, a professor of creative writing at the College of Southern Nevada, was on the phone with her dear friend Brian Dice, a member of the board of the nonprofit publisher McSweeney’s. They were laughing and talking about Black literature, a familiar back-and-forth that has become the soundtrack of a friendship forged years earlier in the Nevada desert. The two had originally met in April 2017 at the Believer magazine’s literary festival in Las Vegas, where they bonded over a shared concern for overlooked works of Black literature, books that were under-reviewed, out of print, or otherwise obscured. Now, a year after a presidential election that still had her reeling, Vital-Lazare was sparked into action. She and Dice wondered aloud over the phone, what if they really did it: “We had this idea together—what would happen if we brought some of those works back?”

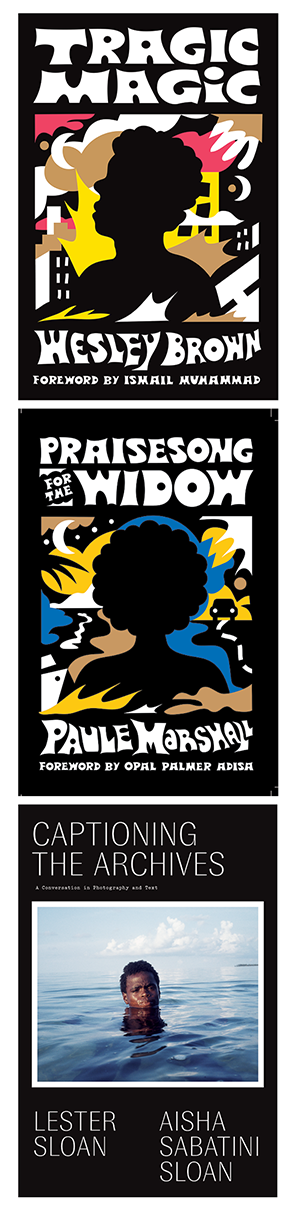

Five years later the fruits of that phone call are bearing out in a book series from McSweeney’s called Of the Diaspora. Edited by Vital-Lazare, the series shines a light on works of Black literature that were relatively overlooked or underappreciated by readers and critics alike at the time of their original publication by reprinting them in new, collectible hardcover editions featuring bold, eye-grabbing cover art by Sunra Thompson. The series debuted in April with Wesley Brown’s 1978 novel, Tragic Magic, the story of a young Black man, a conscientious objector, who has just gotten out of prison after serving a sentence for refusing to fight in the Vietnam War. The novel was edited by Toni Morrison, then working at Random House, who urged Brown to commit to the parts of the story that were most “difficult” or “unsettling.” For Morrison, he says, “that was when the most significant writing takes place.”

Tragic Magic came out in the midst of a newspaper strike that brought books coverage to a grinding halt at several publications. While that may have played a role in his novel’s fate, Brown notes that Black literature is historically under-reviewed. “In our society,” he says, “when you’re talking about embattled groups of people, of which African Americans are one, there is often a sense that the value of their artistic endeavors are not considered seriously, or they’re dismissed outright, or just ignored.” Forty-three years after the novel’s initial publication, its depiction of a country divided over questions of race, class, and gender still resonates, and Brown says he hopes its rerelease will do away with the notion that political polarization is a recent phenomenon in the United States: “I think this country has always been divided,” he says, “since its inception.”

Second in the series is Paule Marshall’s Praisesong for the Widow (Putnam, 1983), the story of a middle-aged woman from Harlem who travels to the Caribbean following the death of her husband. Marshall, the child of poor immigrants from Barbados, infused her novels with the unique culture and linguistic patterns of her West Indian upbringing. In that way her work is part of Vital-Lazare’s broader desire to publish Black voices from across the diaspora. She and McSweeney’s have plans to publish works by Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Brazilian writers in the coming years. “Much of our understanding of Black literature,” she says, “comes from our very particular lens of what is Black American life.” With Of the Diaspora, Vital-Lazare wants to both deepen that lens—bringing in African American voices from the Southwest, for example—and pan out beyond North America.

The third book to be released from Of the Diaspora is Captioning the Archives, a collaboration between photographer Lester Sloan and his daughter, the writer Aisha Sabatini Sloan. The book, which comes out in August, features photographs from the elder Sloan’s twenty-five years working as a photojournalist for Newsweek and includes images from major world events like Pope John Paul’s visit to Mexico as well as scenes of everyday Black life in Los Angeles and Detroit; each is accompanied by a caption in which father and daughter discuss the image. The new edition underscores the significance of Black photojournalism at a time when we are inundated with images of Black people under duress, often at the hands of police, a topic Sabatini Sloan writes about in her essay collection, Dreaming of Ramadi in Detroit (1913 Press, 2017). She recalls her father having “heated conversations with editors” who wanted Sloan to supply them with photographs of Black people that emphasized pain and suffering, which he found exploitative. She recalls the pushback he got over one image that captured the love of a Black father for his child. Editors, she says, often “had this stereotypical vision of Black people they wanted to perpetuate through the photographs they were publishing.” The captions in Sloan’s book provide a window into how people across the world interacted with the Black man behind the camera and fill in anecdotes such as the time Sloan was taking photographs during the fall of the Berlin Wall and heard East Berliners singing the gospel song and civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome.” They walked over to him and said, “We learned from you.”

In fact the Of the Diaspora series itself works like this, by filling in the overlooked pages of a literary tradition that has long fought to be seen holistically, beyond the achievements of a select few. As Vital-Lazare puts it, with these three books and more to come, she wants to give new readers a “360-degree view of Black identity.”

Jennifer Wilson is a contributing writer at the Nation magazine, where she covers books and culture.