In our Craft Capsules series, authors reveal the personal and particular ways they approach the art of writing. This is no. 203.

I grew up in a conservative Christian home in the Midwest where modesty, contentment, and harmony—bent toward conformity—were practiced values. It certainly didn’t mean that there weren’t any disappointments or dissension. It was just that very little, if anything, was said or expressed. Some of us might have heard these phrases if we fussed: You’re making a mountain out of a mole hill. I’ll give you something to cry about. Just ignore it, and it’ll go away. Despite feeling stifled by this repression, I acquired keen observation skills, enabling me to notice fragments of discontent and bits of tension in my home and elsewhere, even when unvoiced. I bring this talent developed in childhood to my contemporary writing, which deepens my work in multiple ways. Consider this excerpt from “Restorative,” a piece from my new book, Perennial Ceremony: Lessons and Gifts From a Dakota Garden, published by the University of Minnesota Press this month:

Deeper now into the woods, I choose the pathway that rolls into a picturesque scene with cedar boughs bent down from the weight of snow and ice. I hear sounds of pheasant wings, likely being flushed out by Rasta. I silently pray they make it to a tree branch. I hear another one as I opt for a right turn out of the woods and onto a trail that circles around the prairie grasses. Rasta now joins me at a slower pace, and I can see her breath with each pant. I take note of the snow art along the trail. Just like when we make snow angels, the prairie grass tips make snow arches from moving back and forth in the wind.

The passage is about a winter walk with my dog, but the essay addresses much more than simply exercising our canine pet. In it, I try to convey how slowing down and being with nature can calm the body and mind and restore our spirits. I could have just written, “Walking in our woods restores me.” But that wouldn’t have been very engaging. Instead I dramatized the process of slowing down through my closely detailed sensory descriptions: “cedar boughs bent down from snow and ice,” for example, and “see her breath with each pant.” I draw on other senses besides the visual: Listening is a crucial part of observation, and in this passage I pay careful attention to the sounds around me in the scene, which include the noise of pheasants, for whom I offer a prayer.

Close observation can also enable a writer to gain insight into past experience, which is relived on the page and benefits from the insight of the present. I utilized this process of reexperiencing a particular event from twenty years earlier for a theatrical introduction to my book Voices From Pejuhutazizi: Dakota Stories and Storytellers (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2022), which recorded narratives told to me by my family and ancestors. In the introduction, I recalled an experience at a workshop during which participants were offered feedback after drawing individual renditions of a tree:

Francis tipped his cowboy hat back, looked at me, and said, “Your tree has no roots.” I replied with silence and a blank stare. I looked down at my wispy, blowing-in-the-wind tree, drawn on the stark white eleven-by-fourteen-inch paper.

“You’re searching for something,” he declared.

This time I responded with a bewildered “What? What am I looking for?”

“That’s for you to figure out,” he replied.

And that was that. My tree reading was over.

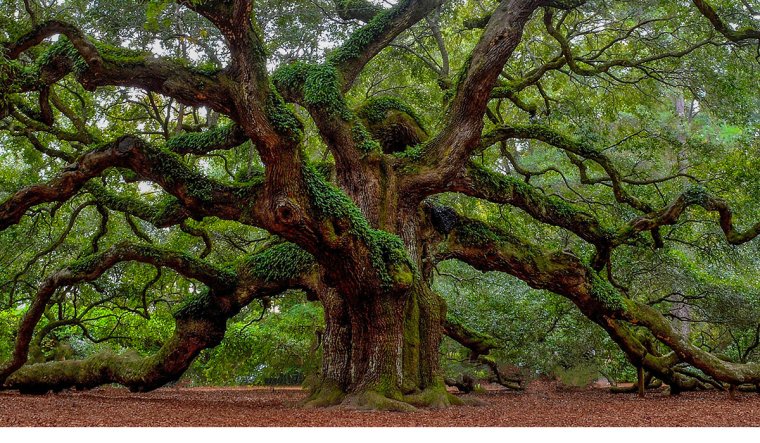

I had held that significant moment of bewilderment for years, and returning to it with deep attention in the introductory essay to my book brought me greater insight: My drawing of a rootless tree revealed my own rootlessness, my own lack of knowledge about my family’s and ancestor’s stories. Later in the introduction I stated my insight plainly: “I was, in essence, a tree with no roots.” I returned again to this insight in the book’s closing chapter, “A Story of Belonging,” which followed all of the narratives I had finally learned and recorded from my ancestors. I wrote, “I imagine if I were asked today for a rendition of a tree, my drawing would look much different from the one I drew twenty years ago. It would be an oak tree, of course.” Not only that, but I could envision the tree clearly, observing it closely in my mind: “Its trunk would be girthy with thick, rough bark and a story nestled within each crevice.” And I imagined how I would “allow this oak’s branches to stretch across the vast blue sky, exchanging stories with those willing to listen and tell their own. ... These are the stories that provide the roots of belonging.”

The keys for a writer to hone their close-observation skills are slowing down, spending time in silence, and noticing the world around them. Try visiting a public space alone, silently observing it, then writing about all that you hear, see, touch, smell, and taste. Or return home to write about a memory that took place there, immersing yourself in that world. Always bring your full self into everyday spaces or events, like walks in the woods or other moments that have yet to reveal their full significance.

Teresa Peterson, Utuhu Cistinna Win, is Sisseton Wahpeton Dakota and a citizen of the Upper Sioux Community. Teresa recently published, Perennial Ceremony: Lessons and Gifts From a Dakota Garden (University of Minnesota Press, 2024). She and her uncle, Super LaBatte, coauthored Voices From Pejuhutazizi: Dakota Stories and Storytellers (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2022), which was selected as the Native American One Read by the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community’s Understand Native Minnesota campaign. Teresa is also the author of the children’s book Grasshopper Girl (Black Bears and Blueberries Publishing, 2022), has poetry in the Racism Issue of Yellow Medicine Review, and is a contributor to the anthology Voices Rising: Native Women Writers (Black Bears & Blueberries Publishing, 2021). Her true passion is digging in her garden that overlooks the Mni Sota River Valley and feeding friends and family.

Art: Andrew Shelley