The ingenious collections included in our nineteenth annual feature celebrating debut books of poetry are composed of poems that were written more than a decade ago, if not a few years back. Given the sheer amount of time that goes into dreaming up, creating, writing, and editing a book, it seems fitting to focus on the past, present, and future aspects of the following ten collections—both temporally and in the collapsing and conflation of the chronological that often takes place within art. In the beginning of the pandemic, Leah Nieboer (SOFT APOCALYPSE) was paying attention to the growing instability and treacherousness of our world and “thinking about the future…as something an erotic trace of the past or present can release, something we can perform through our rhythms of relationship.” In writing the present, Nieboer created a poetics for the future that is intimate, phantasmal, and neon-lit. Ina Cariño (Feast) and Amanda Gunn (Things I Didn’t Do With This Body) offer a physical poetics. Cariño, with their intergenerational and voracious speech, feeds us the brown skin and pink guava insides of the speaker’s body while decentering the fermented milk of the white gaze, and Gunn demonstrates the fragility, will, pleasure, and grief of the body, from Harriet Tubman to the speaker. Elisa Gonzalez (Grand Tour) and Carolina Hotchandani (The Book Eaters) present the delicate poetics of death, exploring a “before-after binary,” as Hotchandani puts it, holding space for the constant transformations of life.

Clockwise from top left: Ina Cariño, Simon Shieh, Amanda Gunn, Carolina Hotchandani, Leslie Sainz, Shaina Phenix, Leah Nieboer, Joshua Burton, Elisa Gonzalez, Kweku Abimbola (Credit: Eugene Smith)

Joshua Burton (Grace Engine) and Shaina Phenix (To Be Named Something Else) showcase a poetics of endurance, in which language is slashed through, redacted, bolded, acted out, and rewritten to a sobering and enlivening effect, respectively, where the “Black-was” meshes with the “Black-is,” per Phenix’s language. Leslie Sainz (Have You Been Long Enough at Table) gives us a revolutionary poetics, diving into the Cuban American experience both personally and historically, with a radically feminine perspective, and Simon Shieh (Master) presents a poetics of emancipation, grappling with and deconstructing the memory of a master figure’s misused power. Finally, Kweku Abimbola (Saltwater Demands a Psalm) gifts us a poetics of healing, turning to Akan tradition as a way of offering rebirth and possibility through elegy.

Though these poets vary in how long it took them to find a publisher, ranging from four months to three years, and in their life experiences, from being a martial artist to a medical copy editor to a member of a post-punk band, these noteworthy writers find similarities in being no strangers to rejection, sometimes counting as many as forty-eight nos before that long-awaited yes. In handling the undulations of the literary life, Cariño tells us that “instead of striving for some abstract capitalist idea of success, remind yourself that your work is not transactional. Let it bloom on its own time.” Sainz echoes a similar tenderness by sharing her list of musts as a writer: “I must write following a warm shower, with at least one lit candle nearby.” In our nineteenth year joyously spotlighting debut poets, we present ten writers who teach us how to explore ourselves—our familial, historical, social, and spiritual lineages and, by extension, our microcosms—and further, how to cast the world anew to create a gentler, more expansive future.

Ina Cariño | Simon Shieh

Amanda Gunn | Carolina Hotchandani

Leslie Sainz | Kweku Abimbola

Elisa Gonzalez | Joshua Burton

Leah Nieboer | Shaina Phenix

Ina Cariño

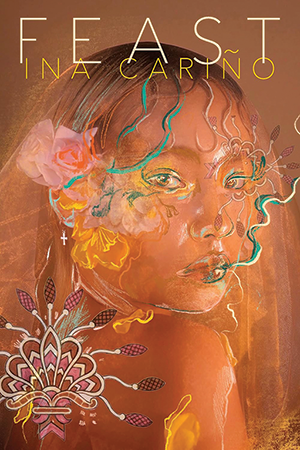

Feast

Alice James Books

(Alice James Award)

in exchange I’ll show you how

to nourish yourself. lift your grandmother’s knife.

slice through the fattest layer in your gut & eat.

—from “Lean Economy”

How it began: The poems in my original manuscript were initially part of my thesis for the MFA program at North Carolina State University, from which I graduated in 2019. Writing a full-length manuscript was at first daunting. I came to the program with a strong writing foundation, but my voice and the direction of my writing were unclear. I often wrote what I now call “surreal fluff”: writing that is pretty and well worded but too “universal” and without much resonance or meaning. I started writing with more focus toward the end of my first year, especially when my thesis adviser, Eduardo C. Corral, encouraged me to write about things that were more tangible in my life—namely my upbringing in the Philippines, my lived experience as an immigrant in the United States, and the ways in which my native languages and, in turn, my identity have been whitewashed over time. I leaned into the idea of intergenerational nourishment and abundance beyond trauma, which is where the food motifs come in. I’ve always experienced the acts of making and eating food as communal and familial, and I wanted to show that in this book.

Inspiration: Making food with my grandmothers, mother, and two older sisters in the kitchen. Matrilineal magic. I lived in a house with all of them as well as my extended family (in many non-Western households, living with titos, titas, and cousins—a slew of people—is not uncommon). So I found the house to be always bustling, especially at mealtimes and during celebrations, for which we’d lay out platters and platters of food for everyone to share, despite money sometimes being scarce. To me, the act of feeding one another is an act of self-nourishment.

One memory that inspired this collection is that of my fifth birthday; my family bought a live suckling pig and slaughtered it in the backyard for the feast. I remember watching the process with both fear and fascination. These ritualistic acts of violence are somehow also those of sustenance: sustenance of body and of culture and identity.

Influences: Because I’d taken a meandering path back to creative writing (I originally aimed to major in music performance on the violin, and only later studied English literature), my introduction to Li-Young Lee’s debut poetry collection, Rose (BOA Editions, 1986), happened much later than it should have. Reading his work for the first time in graduate school was incredibly influential for me. The idea of someone writing in their own voice, with an Asian American perspective, about experiences that aren’t only Asian American, really gave me an opportunity to explore similar sensibilities in my own work.

Dorianne Laux, who was one of my professors in graduate school, on the other hand was someone whose work I’d read even before writing seriously again. She is a master of the extended metaphor and I think she really embodies intellect, image, and emotion in most if not all of her poems. She also has a generous spirit and is so nurturing to her students. Her work is very different from mine, but I’ve learned a lot from her.

I also believe my music studies over the years have contributed to the application of rhythm and the sense of musicality in my writing. I’m inspired by the polyphonic, nuanced, and complex simplicity of Bach and Vivaldi; the lively verve coupled with darkness in Mendelssohn’s and Beethoven’s work; the boldness and overflowing abundance of Tchaikovsky; Ravel, Coltrane, ESG, Caroline Shaw, Blood Orange, BADBADNOTGOOD, Yaeji—I could go on. Music is extremely influential on my poetry.

Writer’s block remedy: I turn to other art forms and let go of my writing for a while. I’m in a post-punk band, and we regularly play shows, so that gives me a different creative outlet. In addition to playing music, I also draw and paint. At the end of the day, though, I’ve always felt reading, and reading widely, is what stokes my creative fire and sustains my writing practice. I try to read living, breathing writers’ works. It’s so important to champion your contemporaries, as well as those who’ve come before.

Advice: I think we’ve all heard “try and try again.” It’s important to persevere, yes, but I think it’s more important to be kind to yourself in the face of rejections. To be gentle when critiquing yourself. To remember that everyone has a different pace, a different trajectory, some landing sooner than others, and that’s okay. Instead of striving for some abstract capitalist idea of success, remind yourself that your work is not transactional. Let it bloom on its own time. For those who have landed their manuscript at a press, take your time and make sure that the press’s values align with your own, and that they’ll treat you and your work with respect.

Finding time to write: This is a tough one because I’m busy juggling so many projects at the moment. I’ll admit, I take on too much. I’m the kind of writer who doesn’t have a daily writing practice, which somehow still works for me. Oftentimes I find that I’ll think of a line before going to bed, or I’ll wake up in the middle of the night with a line in the forefront of my mind. I once drove home with a line stuck in my head that eventually turned into the last poem in Feast. I write sporadically, so I take it as it comes and write little bits down as much as I can, until I can find a bigger of chunk of time to sit and flesh it out.

Putting the book together: In graduate school I was discouraged by my professors and peers from being too “on the nose” in ordering my poems; for example, I don’t think Feast would have worked had I ordered it chronologically. It takes the surprise away; it feels expected. Instead I looked for motifs and common words between my poems, how they spoke to each other depending on placement, and how different elements were emphasized depending on where in the manuscript they were. That’s what I love about poetry collections, as opposed to anthologies or novels, the poems are in a threaded conversation with each other throughout the collection, even as they stand alone. Regarding sections, I think of them as little worlds within a larger ecosystem. These worlds can group poems by era, or they can be dominated by a particular tone or voice. It’s important to take your time with ordering.

What’s next: I’m working on refining my second manuscript, which is slated to come out in 2026 with Alice James Books. I’m excited to eventually share it with the world!

Age: 35.

Residence: Raleigh, North Carolina.

Job: I sling espresso five days a week in downtown Raleigh. I run a reading series centering marginalized poets and other creatives in the Research Triangle area. I also take on manuscript consultations, give readings, and teach workshops.

Time spent writing the book: About a year in graduate school.

Time spent finding a home for it: About a year and a half.

Recommendations for recent debut poetry collections: This year I’ve really enjoyed I’m Always So Serious by Karisma Price (Sarabande Books), Couplets: A Love Story by Maggie Millner (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), and ASTERISM by Ae Hee Lee (Tupelo Press, 2024).

Feast by Ina Cariño

![]()

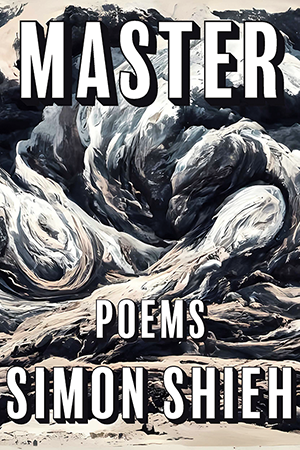

Master

Sarabande Books

(Kathryn A. Morton Prize in Poetry)

To spite me, he hid the moon

in the shadow of a jackrabbit, the deepest craters

in its eyes.

—from “Master (Five Nocturnes)”

How it began: I started writing this book at twenty-four, soon after returning to Beijing to teach English at a university. Beijing was the city where, at fifteen, I first found refuge from the person who inspired the book’s master figure. Returning there felt like returning home, and everything I was too young to process as an adolescent poured out of me as poetic language, giving way to memory. I wrote the first line of the poem, “Self-Defense,” which reads, “To be saved and unsaved,” and I really believe the book originated in that line. I’d written poems before, but they all felt like exercises. “Self-Defense” activated something I didn’t know existed, the beginnings of what I immediately recognized as the subject of a book that was inside me. It was the first poem I wrote that felt like it was mine. I knew immediately that this book would be called Master, but this collection really took shape when I realized it is not about the one who, in childhood, I called master. It is about the speaker, his loyalty to the master despite the master’s tyranny, and his eventual liberation from this authority figure.

There is one more catalyst I need to mention. Before writing poetry, I was a martial artist who distrusted what I saw as the artifice of language. Instead, I spent years expressing myself through combat, with the belief that what I experienced in the boxing ring was more real than anything expressed through language. Jericho Brown’s The New Testament (Copper Canyon Press, 2014) showed me that poetry can use language and white space to transcend and spark visceral sensations beyond language. With the poems in Master, I aspired to do just that.

Inspiration: Reading other poets’ first books and feeling the energy and momentum unique to great debuts inspired me to sustain the impetus of Master despite my changing feelings about it. Notably, the first books of Eduardo C. Corral, Jenny Xie, J. Michael Martinez, Richard Siken, Mai Der Vang, Taylor Johnson, Natalie Diaz, Sally Wen Mao, Thomas James, Ocean Vuong, Ilya Kaminsky, Sylvia Plath, and Jenny George were guiding lights.

Poets & Writers’ annual debut poets feature inspired me anew each year when the prospect of writing and publishing my collection felt bleak, as did Dan Chiasson’s poetry reviews, and podcasts like VS, Between the Covers, the New Yorker’s poetry podcast, and the Poetry Magazine Podcast.

Derek Walcott’s sun-drenched islands and James Wright’s rainy Midwestern plains; Thomas James’s and Eduardo C. Corral’s imagery; Jericho Brown’s line breaks; Lucie Brock-Broido’s and Carl Phillips’s verbal singularity; the Tang poets’ silences; Louise Glück’s poetic sense of narrative; Terrance Hayes’s wild voices; Julia Kristeva’s Revolution in Poetic Language (Columbia University Press, 1984); Jacques Lacan’s seminars and writings; Ocean Vuong’s tenderness; Jean Valentine’s mystery.

Sherwin Bitsui’s undergraduate poetry workshop at San Diego State University gave me permission to take my writing seriously and Sally Wen Mao’s poetry workshop, part of the DISQUIET International Literary Program, provided me with vital feedback on my poems.

The places and weather of Beijing and upstate New York.

Finally, this book would not exist if not for the many long conversations I had with my wife and best editor, Charlotte.

Influences: There are three collections that I can say really changed me. First, Jericho Brown’s The New Testament—which begins, “I don’t remember how I hurt myself,”—showed me that mystery, not meaning, is the poem’s origin and its purpose. Second, Eduardo C. Corral’s Slow Lightning (Yale University Press, 2012) made me feel like I was discovering a new genre, a new way of writing, a new way of seeing the world; his imagery and temporal gestures changed what I thought a poem could do. Finally, Terrance Hayes’s Lighthead (Penguin Books, 2010) showed me the poem’s affinity to the unconscious, which is also the source of its music.

Writer’s block remedy: I used to think I could outwork burnout and writer’s block (an impulse I attribute to my experience as a martial artist, when I had to fight through exhaustion), but I’ve figured out that the impasse is productive for the poet—that’s where the thinking, the process happens. The poem is a by-product of the impasse. When I don’t know what to write, I do anything but write and trust that the poem is writing itself in my body, waiting to be heard. I also do a lot of my writing and revising on my Notes app while I’m walking.

Advice: My first book gave me a lot of grief! Every rejection hurt, and there were forty-eight of them. There were times when I felt like scrapping half of the manuscript. There were times when I felt like scrapping the whole thing. I gradually learned to disassociate my work from the process of publishing it, but unfortunately this only came with failure. I learned that every reader and word of feedback is a blessing, not to be taken for granted or even expected. I learned that I am not a writer but a student of poetry.

Finding time to write: Writing this book taught me a lot about my process. These days, I need longer holidays to do any substantial writing, and as a high school teacher I’m fortunate enough to have that. Longer stretches of time allow me to immerse myself in the work, which is necessary to start new projects, or forge new paths in existing projects. But writing is only a small part of the process; reading, enjoying time with my family, enjoying time alone, and exercise are all integral.

Putting the book together: My wife, Charlotte, played a big part in this, as I had trouble seeing the poems from a distance. She revealed to me the narrative arc that the poems were suggesting, and in doing so opened up the manuscript to more fully include the process of narrativizing and poeticizing my experiences. The order changed many times. New poems entered and old poems fell out. A poet I admire greatly told me that even if you think the manuscript is finished, it’s not, there’s still more to be done. I didn’t stop trying to make it better until Sarabande sent it to the printer.

What’s next: I’m working on something totally different, which feels great. This new project is still forming so I won’t say much about it, other than its influences are totally distinct from those for Master, and the impulses behind it are different as well.

Age: 32.

Residence: Washington, D.C.

Job: I teach Theory of Knowledge to eleventh and twelfth graders.

Time spent writing the book: I wrote the first poem in 2016 and the last one in 2019.

Time spent finding a home for it: Three years, over which the book changed shape many times.

Recommendations for recent debut poetry collections: Leslie Sainz’s Have You Been Long Enough at Table (Tin House), Gabrielle Bates’s Judas Goat (Tin House), Dong Li’s The Orange Tree (University of Chicago Press), Sahar Muradi’s OCTOBERS (University of Pittsburgh Press), Xiao Yue Shan’s then telling be the antidote (Tupelo Press), Alexa Patrick’s Remedies for Disappearing (Haymarket Books), and Jane Huffman’s Public Abstract (American Poetry Review).

Master by Simon Shieh