This past spring, poets and teachers Beth Ann Fennelly and Catherine Pierce organized hundreds of Mississippi educators to sign an open letter opposing guns in the classroom. “A classroom with a gun ceases to be an environment where teachers or students can feel safe engaging in the sorts of stimulating and challenging discussions that are the hallmarks of higher education,” they wrote. The petition, signed by more than three hundred educators from throughout the state, opposed HB 1083, a “campus carry bill” that would make it easier for gun owners with enhanced concealed carry permits to carry firearms in spaces like classrooms and dormitories. After weeks of debate about language and amendments, the bill eventually died. “I wouldn’t say it was due to us,” says Fennelly. “But we were able to shape public perception.”

Beth Ann Fennelly, Lisa Moore, Erika Meitner, and Catherine Pierce. (Credit: Fennelly: Mike Stanton; Meitner: Toya Earley; Pierce: Megan Bean)

In recent years no classroom space has been free from the specter of gun violence. Shootings at schools from Virginia Tech to Sandy Hook Elementary School have been followed, in some states, with “campus carry” bills that would bring more guns into institutions of higher learning. All of this has put faculty on the front lines of a debate about gun violence that they might never have imagined participating in when they chose their career path. As creative writing teachers, Fennelly and Pierce, who teach at the University of Mississippi and Mississippi State, respectively, can both attest to the importance of a safe classroom environment. “[Catherine] and I have discussed how creative writing workshops are places where emotions run high,” Fennelly says, “and how dangerous it would be for discussions like this to take place with guns on hand.”

It isn’t always easy for educators to be heard. At the same time faculty were fighting the Mississippi bill, officials from the Southeastern Conference, an athletic conference of fourteen major Division 1 universities in the southern part of the United States, were speaking out against the bill’s provisions allowing concealed carry inside football stadiums—a request that was conceded by legislators. “Because it’s football in Mississippi, everyone was like, ‘Okay, no concealed carry in stadiums,’” says Fennelly. “They get listened to because they have dollars—but we don’t have dollars; we have words.”

As Fennelly and Pierce planned their response to the proposed bill, the pair looked to other educators for advice. Fennelly reached out to Lisa Moore, a poet and professor of English and women’s and gender studies at the University of Texas in Austin, who had similarly found the gun debate at her classroom doorstep in 2015. That was the year Texas’s own campus carry bill—which would allow concealed weapons on campus under certain conditions—was passed by the Texas legislature and signed by the governor. Though Moore opposed gun violence, she hadn’t previously been an activist on the issue. “This really handed us as faculty a microphone to say with credibility: This is one place where we absolutely know guns do not belong,” she says.

During the period after the Texas bill passed in 2015 and before it took effect in 2016, Moore and her colleagues banded together to, in her words, “make dissent visible.” Preparing for their initial rally, she and another professor made signs, each one bearing the name of someone who had died in a campus shooting. “Unfortunately there were lots of those,” she says. At the protest the faculty went to the microphones and read names, short statements, and the date of each victim’s death. “As simple as that was, it provided an opening for this overwhelming wave of protest,” Moore says. The actions and community discussions that ensued involved everyone from students and faculty to campus security and administrators. “Everyone knew it was a bad idea,” she says about the bill. “It was nothing but a form of ideological bullying to make sure we shove guns into every corner of society.”

Although the law eventually went into effect, Moore and two fellow professors, Jennifer Lynn Glass and Mia Carter, didn’t give up. In the summer of 2016 they filed a lawsuit against the University of Texas and the Texas attorney general’s office in an attempt to block implementation of the law on campus, arguing in part that guns on campus would jeopardize students’ First Amendment right to speak freely in the classroom. A federal judge eventually ruled against the case in July of last year, stating that Moore, Glass, and Carter presented “no concrete evidence to substantiate their fears, but instead rest on ‘mere conjecture about possible…actions.’”

Despite these setbacks, Moore has hope for the future—not least due to her longtime experience advocating for LGBTQ rights on campus. “We had been focused on getting equitable benefits for employees with same-sex partners,” says Moore. “Nothing worked, but at the same time, everything we did led to the culture shift that eventually made gay marriage legal nationwide.” Of the gun debate she adds, “I see this as that kind of long-range cultural change we’re going for. The win or loss of any particular action is not as important as continuing to create space for dissent and [nonviolent protest].”

One of the ways to create that space, Moore and her fellow educators believe, is by writing. “Any time you mourn or mark something of importance, you need a poem,” she says. “We need powerful words to connect with one another and to remind ourselves that we are the peaceful majority.” Poet Erika Meitner is one of the writers making the gun issue central to her work, as well as to her activism. She signed a contract for a teaching job at Virginia Tech in April 2007, just a few days before the mass shooting on campus that killed thirty-two and wounded seventeen. “My first classes of undergraduate and graduate students had experienced the shooting,” Meitner says. “It was a community in trauma.” In addition to affecting her pedagogy, the subject seeped into Meitner’s own work. In her forthcoming poetry collection, Holy Moly Carry Me (BOA Editions, September), she writes, “I ask my son what he would do if someone came to his school with a gun. / I would take my friends and hide, he says. I would be very quiet.”

Pierce points out, however, that activism can come at a cost to creativity. “When I’m calling legislators and researching bills, there’s no mental space for me to be writing,” she says. “Likewise, when I’m working on a poem, I can’t pause it to shift over into activism for a little while.” Still, Fennelly and Pierce believe the work is worth it—and they are remaining vigilant. “It probably will come up in legislation again, and then again, and again,” says Pierce. “I won’t be blindsided by it next time and can jump right back into work.”

Moore also notes that the future of activism lies in the hands of students rather than teachers, citing this year’s surge of student-led activism following the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. In recent months both Meitner and Moore have taken their own kids to major rallies in the wake of that tragedy. It is the young people signing on to this fight, Moore says, that gives hope. “Youth movements have energy, power, wit, and savvy,” she says. “That tends to be what carries the work of changing a culture.”

Sarah M. Seltzer is a writer of fiction, creative nonfiction, journalism, and ill-advised tweets. A lifelong New Yorker, she is an editor at Lilith magazine.

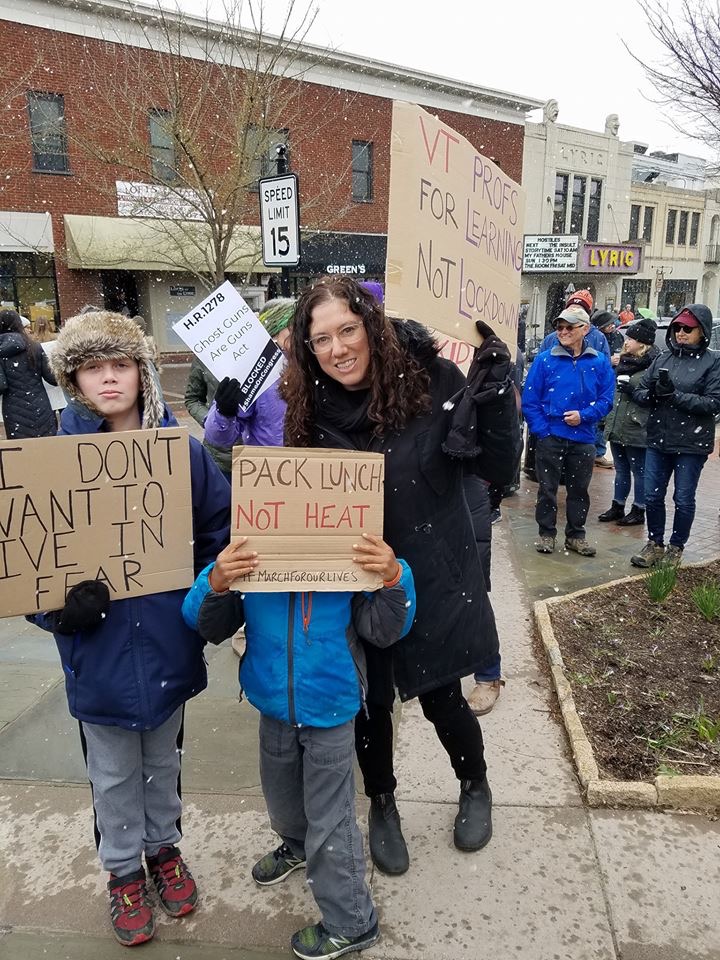

Above photo: Erika Meitner and her two sons, Oz Trost (left) and Levi Trost (center).