In our Craft Capsules series, authors reveal the personal and particular ways they approach the art of writing. This is no. 127.

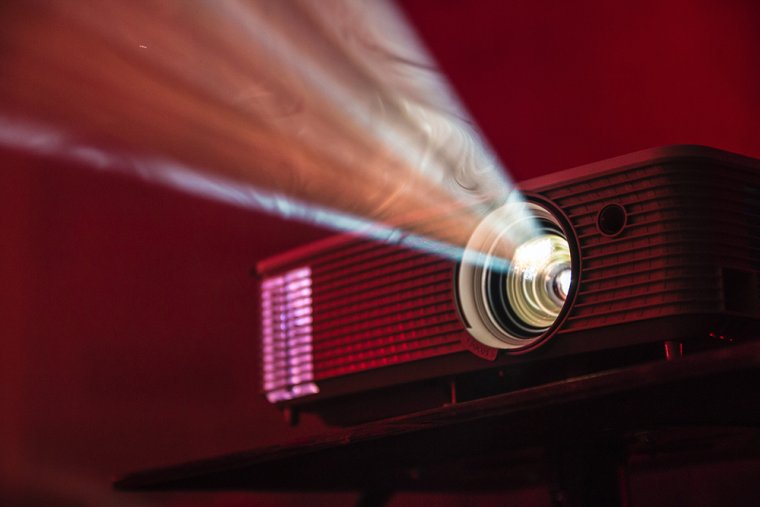

There were few things that brought me more joy as a child than when my dad took the slide projector and folding screen out from the closet and set them up in our living room. We had a stack of carousels filled with slides chronologically arranged within large plastic rings. Like silent movies from the past, the slides transported me to places and times that preceded my birth and were not part of my memories. Sitting on the couch in our darkened living room, listening to the loud whir of the projector’s fan as images from the family archive glowed on the screen, an imaginative space opened up inside of me. In my mind I entered the vivid images, wanting to know everything about them—Where is that? Who is that? How are they connected to me?

There were many photos in which different configurations of family members posed in various homes in Cairo belonging to my relatives. There was my maternal grandparents’ aging villa and my paternal grandparents’ familiar and cozy living room, my uncle and aunt’s museum-like apartment densely cluttered with antiques, and the dwellings of other aunts and uncles enlivened by dark wallpapers and gauzy drapes and ornate brass chandeliers. I loved all of the people in the pictures, and I was also besotted with these settings, places that were familiar to me from visits to Egypt, but all somewhat hazy in my memories.

My parents emigrated from Egypt three years before I was born, settling in Canada and eventually in the United States. We traveled to their homeland almost every year, my parents scrupulously saving to fund these trips, especially in the beginning when they were living lean on graduate student salaries. I had my obsessions with photo-objects in Egypt, too. My grandmother kept a collection of black-and-white pictures in a red cookie tin with a white woman’s face on it. The ritual of opening that box and going through the prints was something I looked forward to every year. I slowly studied the familiar images, like savoring a delicious piece of chocolate cake. These photographs were generally from the 1950s and 1960s, decades older than the Kodachrome slides we had in Denver. They pictured a more spacious and elegant version of Cairo than the dense and hectic metropolis that I knew. A strong European influence was evident in my distant relatives’ fashion, a stark contrast to my immediate relatives’ less form-fitting, conservative wardrobes.

I likely inherited my love of photography from my father and his older brother Lotfy. The two of them were always in possession of still cameras and an assortment of ever-advancing movie technologies, from Super 8 to video cameras. I eventually followed their lead, requesting cameras for birthdays and studying photography in high school and college. After graduating from college, I worked for a gallery that specializes in photography and after that took a job in the photography department at the Museum of Modern Art. MoMA has an extraordinary photography collection and working with it for four years gave me a robust education in the history of the medium. Unlike my colleagues who had an eye and an appetite for acquiring work by contemporary photographers for the museum, my interests lay entirely with historical photographs. At the time I thought of this as a professional failing, but looking back it makes sense why I gravitated toward photographic documents from the past.

Archival photographs were essential to me when writing my debut novel, Country of Origin. I relied on my family’s collections, as well as amazing digital archives one can access online, including the Arab Image Foundation. To imagine myself into the Egypt of my novel, I studied photographs that evoked past versions of Cairo and anchored my imagination in physical facts and details. The villa where the character Halah grows up is directly inspired by my grandparents’ house. My grandmother lived there until I was fifteen, and I spent many long summer days exploring its aging corridors. It felt like something from another time, and indeed it was almost a hundred years old by the time I arrived on the scene. My memories of the house are imprecise, but the pictures remind me of the stucco walls and the intricate wooden lattice work that covered the windows. They help me remember what hung on the walls and the contours of their Louis XVI–style furniture.

Photographs are powerful tools, portals into bygone times. What else can describe the architecture, furniture, decor, food, clothing, and styles of a particular era as well as pictures can? Since the middle of the nineteenth century, we have had these remarkable records of the past. It is difficult for me to imagine writing historical fiction without them. Would I have found my way to writing if I did not first discover my love of photographs? Probably. Have photographs enriched my creative life and helped me imaginatively travel through time? Certainly. My passions for writing and pictures feel very interrelated. I am not sure who I would be as a writer—or as a human—without these means of expression.

Dalia Azim is the author of the novel Country of Origin, forthcoming from Deep Vellum on April 12. Her writing has appeared in American Short Fiction, Aperture, Columbia: A Journal of Literature and Art, Glimmer Train, Other Voices, and the Washington Post, among other publications. She lives in Austin, Texas.

Art: Alex Litvin.