Reginald Dwayne Betts didn’t consider himself a reader until he was sent to solitary confinement for the first time. Betts, then a teenager serving an eight-year prison sentence for carjacking, was surprised by what he saw: a world centered in many ways around books. “I witnessed men setting up elaborate pulley systems to drop books in bags and send them through the air, thirty to forty feet from building to building,” he says.

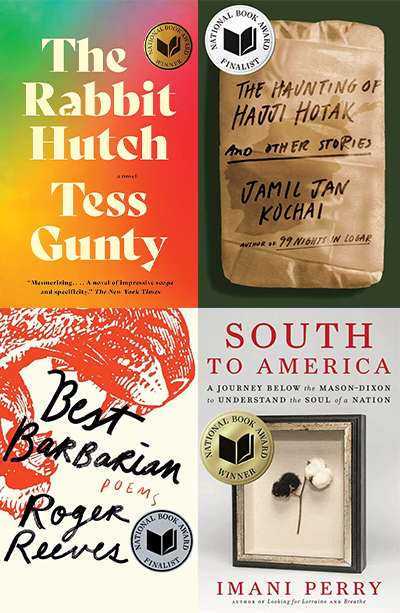

The four titles above will be read by three hundred incarcerated readers at a dozen prisons in six states, and one will be awarded the inaugural Inside Literary Prize in June.

It was the beginning of Betts’s life-changing love affair with literature. After his release in 2005, he published a memoir and multiple critically acclaimed poetry collections. He also established Freedom Reads, a nonprofit that builds libraries and promotes literary life in prisons across the United States. Now he’s helping to facilitate the first national book prize in the U.S. judged exclusively by incarcerated people: the Inside Literary Prize.

To that end, three hundred readers serving time at a dozen prisons in six states have spent the past several months reading and discussing four books named finalists or winners of last year’s National Book Awards: Tess Gunty’s novel The Rabbit Hutch (Knopf); Jamil Jan Kochai’s story collection, The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories (Viking); Imani Perry’s nonfiction book South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation (Ecco); and Roger Reeves’s poetry collection Best Barbarian (Norton)—all published in 2022. The judges received copies of the books through Freedom Reads and its partners on the project: the National Book Foundation, the Center for Justice Innovation, and Lori Feathers, a podcaster, publisher, and book critic.

The winner of the award, honoring the title the incarcerated readers find most moving, powerful, or worthy, will be announced in June. While the National Book Awards offer prizes in different genre categories, the Inside Literary Prize allows readers to consider multiple genres for one award. “We believe that readers don’t believe these categories are silos,” says Betts. “We wanted to honor the porousness of it all.”

The Inside Literary Prize is based on the French Goncourt des Détenus (“Inmates’ Goncourt”), itself launched in 2022 as an offshoot of the country’s prestigious Prix Goncourt, awarded annually for an outstanding work of prose. Just as the Goncourt des Détenus goes to one of the Goncourt finalists, an Inside Prize selection committee—including currently and formerly incarcerated people, writers on the outside, and librarians from various departments of correction—spent months working their way through the finalists of the 2022 National Book Awards to arrive at the four-title shortlist, announced in December. (The program used the 2022 finalist roster rather than the slate from 2023 because the more recent titles were not yet available in paperback; hardcover books are viewed as potential weapons or hiding places for contraband and rarely allowed in prisons.)

From there Freedom Reads drew on its existing network to connect with participating prisons, engaging twenty-five judges at each site in deliberation sessions throughout this spring. That means giving people who have seldom been asked their opinion by culture makers an opportunity to speak up on literary topics. “I’ve been telling them they should talk about these books the same way they talk about the Super Bowl,” Betts says. The organizations have also planned events open to the general prison population, such as author talks and workshops.

With an eye toward making the Inside Literary Prize an annual affair, Freedom Reads has already ordered the 2023 National Book Award finalist titles it will need to deliver to create a 2025 shortlist. But programming in prisons is almost never simple, and the prize’s future beyond June is still full of question marks. Natalie Green, the National Book Foundation’s director of programs and partnerships, refers to this as a “pilot” year; Betts calls it “a work-in-progress.” Even plans for how the winner will be feted—such as via a ceremony or celebration—remain hazy.

Still, the goal of making the Inside Prize an annual award is an important one for Betts, who says it represents a chance to use the medium of high culture to spread awareness about and humanize a population that so many discount and ignore. “What does it mean to make prison a part of the fabric of American literary life?” he says. “If you make it a part of the fabric, you end up having to think about what prison is and means.”

That’s not to say that participating in the prize deliberations won’t be powerful or useful to the judges themselves. Being invited “to choose an award is important for saying you’re part of the community, part of society,” Betts says. “So much about being incarcerated says you’re not.”

Like Betts, Bobby Bostic found a love of reading in solitary confinement. Bostic was serving a 241-year prison sentence in Missouri, for armed robbery; the experience sparked a relationship with books that changed his life. “Reading opens up a whole different world to you,” says Bostic, who was released on parole in November 2022 and has since self-published multiple books and worked with outlets such as the Marshall Project. The existence of an award like the Inside Literary Prize feels like a “miracle,” he says—one that he predicts will provide its judges essential hope and motivation.

Betts has not forgotten how important that hope can be. Although in the years since receiving parole he has helped judge a number of mainstream literary awards, it wasn’t so long ago that he was in a cell alone, discovering firsthand the power of a good book. When a title wins the Inside Literary Prize, that will be a message from its judges: that it “helped them get through another night when they thought nothing else would,” he says. He would rather win that over a National Book Award any day.

Alissa Greenberg reports at the intersection of science, history, and culture. Her work has appeared in the Atlantic, the New Yorker, Smithsonian, and elsewhere.