This summer Alice Quinn will step down as the executive director of the Poetry Society of America (PSA), a position she has held for the past eighteen years. During her tenure, the PSA launched multiple new poetry prizes, organized hundreds of events across the United States, and expanded the Poetry in Motion program, which brings poetry into U.S. transit systems. Previously, Quinn was the poetry editor at the New Yorker for twenty years and an editor at Knopf for more than ten years. She also teaches at Columbia University and is the editor of a book of Elizabeth Bishop’s writings, Edgar Allan Poe & the Juke-Box: Uncollected Poems, Drafts, and Fragments (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), as well as a forthcoming book of Bishop’s journals. A few months before departing the PSA, Quinn, accompanied by her dachshund, Daisy, talked about her work at the nonprofit organization.

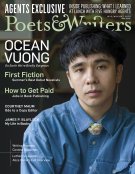

Alice Quinn (Credit: Tony Gale)

What are you most proud of achieving at the PSA?

I’m proud of Poetry in Motion, which recently celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary in New York and its twentieth in Los Angeles. We have a new transit initiative in partnership with San Francisco Beautiful that is a wonderful variation on the program involving local artists and poets. I’m also thrilled with our PSA Chapbook Fellowship program, founded in 2003, which has launched the careers of sixty-four new poets selected and introduced by major figures. We also have two splendid new prizes to add to our distinguished roster of annual awards, the Four Quartets Prize for a unified sequence of poems…and the Anna Rabinowitz Prize for an interdisciplinary project involving poetry and any other art.

And I’ve loved our innovative programming. We’ve presented more than seven hundred programs since I joined the PSA, many of them multi-arts events with actors, musicians, and great visuals. We’ve had vibrant tributes honoring twentieth-century Polish poetry, Black iconic poets of the twentieth century, classic poets and beloved contemporaries—Philip Larkin, Gwendolyn Brooks, Galway Kinnell, Seamus Heaney, Jean Valentine—and we’ve celebrated major anniversaries of institutions like our own; the PSA was founded in 1910.

I’ve also been gratified by our more than forty partnerships with fellow cultural institutions allowing us to reach many new audiences with poetry—perhaps chief among them the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx, where we’re in our tenth year of presenting poetry with each new seasonal exhibit. That alliance is generating more and more collaborative opportunities, including an “Elizabeth Bishop in Brazil” day at the start of the garden’s Roberto Burle Marx exhibit this June.

Why did you choose to step down now?

I thought I might stay until I’d reached the twenty-year mark, but eighteen-plus seems just fine. And I’ve been working on the journals of Elizabeth Bishop for too long. I have a new home in the Hudson Valley not far from where Bishop’s papers are lodged at Vassar, and I’m so excited about that. The archive is closed during the week, so for years I’ve had to use my vacations and a day here and there to access the archive for Bishop projects. I’m sure there will be programming in my future because I have a talent for it, and knowing an audience has been swept up by poetry in a lasting way matters to me. But new leadership can be galvanizing, and I know the PSA will find someone great for this position.

There are a number of organizations in New York City that support poetry, such as the Academy of American Poets and Poets House. What has distinguished the PSA?

I think the PSA has always had a special focus on enlightening people about the power of poetry and the special space it can have in your life—how if you encounter it alone or by surprise in a public place, you can be affected and reminded of actually how powerfully you are able to receive the wisdom and force of poetry. Our programs build on that and send a message that poetry is not too difficult or that it belongs to only one moment in college or to a fervid moment when you were a child.

PSA events also seem to be very interdisplinary, right?

We’ve emphasized a lot of multi-arts programming—we have to think of programs where we can partner. Is there a great show at the International Center of Photography [ICP] of Lewis Carroll’s photographs? Then I know just the person who can recite “Jabberwocky.” Or is ICP showing the work of the great environmental photographer Sebastião Salgado? Let’s bring down Jorie Graham and poets who really care about [the environment] to read. When we had a tribute to Philip Larkin to coincide with Farrar, Straus and Giroux’s publication of a new complete collection of his poems edited by Archie Burnett, I thought we should include jazz because Larkin loved jazz. So I called [PSA board president] Kimiko Hahn, who teaches at Queens College, and said, “Doesn’t Queens College have a jazz band?” And so they came, and we had young students playing jazz at the event. And that’s how you do it—that’s why programming is fun. You can bring people in from various other worlds, and it animates and it proves poetry is part of the cultural scene.

The PSA has allowed me to celebrate and hold aloft the poetry of the past that I love so much and at the same time welcome new work and configure multi-arts programs that are relaxing and illuminating and not tendentious or rote in any way—just a fresh way of looking at poetry and integrating it into your life. And it’s meant a lot to me to pay tribute to the poets that I love—it makes me realize how long I’ve been living with the work of many of these people. I’ve been reading poetry for a long time. I used to go into the Gotham Book Mart [in New York City] and stand there at the little table, read for two or three hours, and walk out with two books. At the Grolier up in Boston—I was a waitress at the time and would go during my lunch break in my waitressing uniform—I would be leaving with my little stack of books, and the founder would say, “Alice, you know, it’s absolutely remarkable, but all these are on sale today for two dollars.” And that’s poetry! People who love poetry want to press it upon other people.

In a Q&A for this magazine in 2008, you said poetry had gotten “swervier.” Do you think it has continued to get swervier?

I think poetry has gotten more traditional as well as swervier. There’s a lot of white space. There are many more sequences that hearken back to traditional poetry. There’s a lot of going back and rediscovering and recontextualizing and learning from moments when the voice in literature sounded different and the use of argument was more profound. Argument matters in poetry. There’s also much more excitement and openness about the field, and it just keeps getting better and better.

We’re in a really interesting moment—Cave Canem has become so significant, as has CantoMundo, Kundiman, and the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. We’re way into a second and third generation of inclusivity in our world. And these poets are doing what T. S. Eliot said poets do in his essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” The really true poets join the poetic and artistic tradition and alter it kind of chiropractically. They alter the spine of it; they alter the future of it.

What have you loved about your job?

I’ve loved the independence and the teamwork. If I meet someone at a dinner party or a lecture, and we start conversing and spontaneously come up with an idea for an event, I can just run with it, and wonderful Brett Fletcher Lauer, our deputy director, has been with me all these years. With Madeline Weinfield and Azzuré Alexander, we are a lean, very effective team, and that’s been exhilarating.

Dana Isokawa is the senior editor of Poets & Writers Magazine.