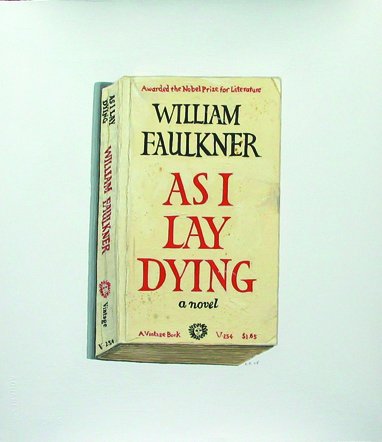

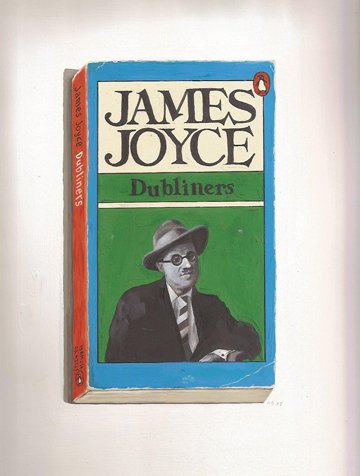

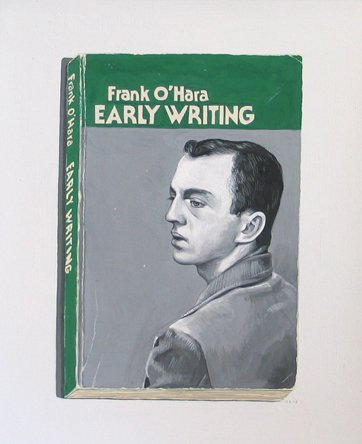

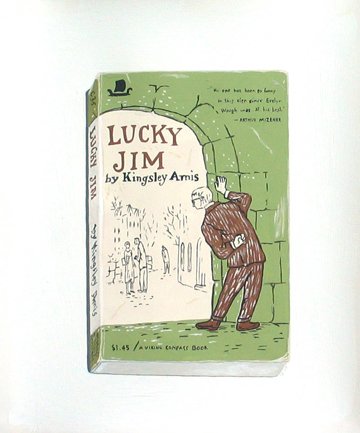

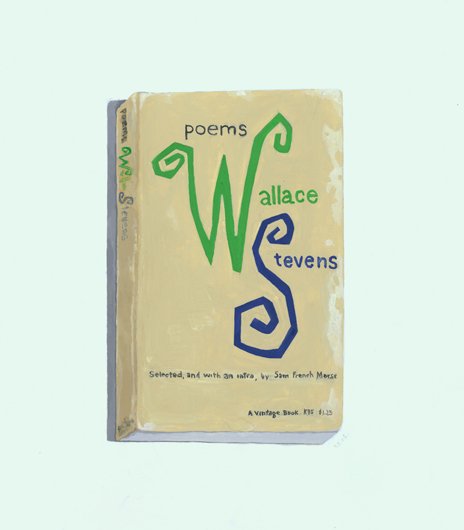

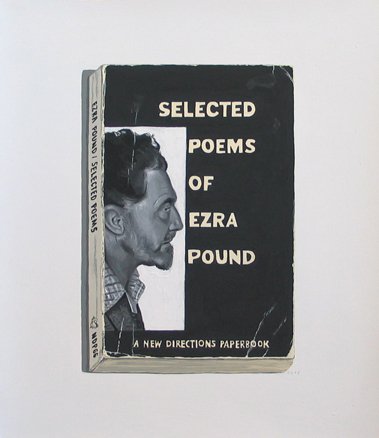

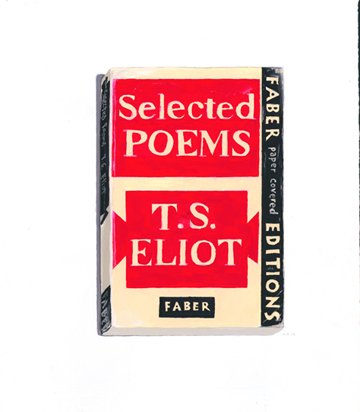

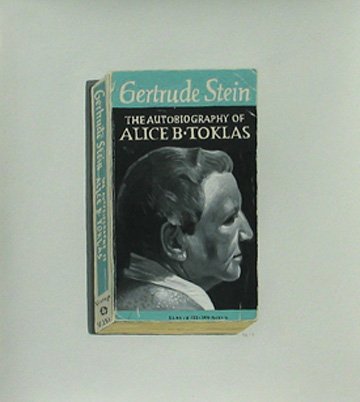

As more readers choose a nifty gadget like the Amazon Kindle or the Sony Reader over a hefty new hardcover; a simple e-mail from a subscription service like DailyLit over a letterpress chapbook; or a flashy iPhone application such as Stanza over the soft dog-ears of a well-worn paperback, those who still appreciate and even celebrate those objects made solely of paper, ink, and glue will likely respond to the work of forty-nine-year-old painter Richard Baker.

"For twenty years or so I have been committed to the painting of still life," Richard Baker writes. "I say 'still life' purely as a descriptive term—the associations conjured by its use seem limited and confining for my purposes. Many of my works from the previous ten years have commingled depictions of two-dimensional representations with diverse 'rendering' of three-dimensional forms—into these hybrid conglomerations I introduced images of books in 2004."

"Books have always been important to me—from the first set of World Book Encyclopedia in my childhood home, through my first jobs in bookstores, to my readings in college and beyond," Baker writes. "They always contained promise, optimism, and desire. They empower, ennoble, entertain."

"As physical objects they are powerful fetishes, icons, containers of every conceivable thought and/or emotion," Baker writes. "We cart them from home to work on our commutes and they accompany us on vacations. We move them carefully packed in boxes from one domicile to another, from one phase of life to another."

"They come to stand for various episodes of our lives, for certain idealisms, follies of belief, moments of love," Baker writes. "Along the way they accumulate our marks, our stains, our innocent abuses—they come to wear our experience of them on their covers and bindings like wrinkles on our own skin."

"As our personalities are changed (or not) by them, so too do they absorb impressions of our lives," Baker writes. "Each book becomes its own unique individual, most especially true of the lowly paperback."

"Which books to paint then?" Baker writes. "I began to think about books that had been important and life-changing for me, but which I now felt I could no longer return to—books that held great meaning for me as a youth but lacked the same impact upon rereading."

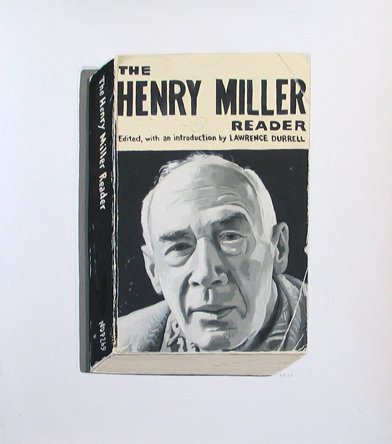

"I wanted to move to Paris after reading Henry Miller; Celine spoke directly to my most disaffected adolescent angers and frustrations, Hamsun mirrored my own tender love of romance (and love of love) and the consuming power of infatuation; I identified with the pointed absurdity of Jarry’s “Ubu Roi” and wished to be a playwright; Camus revealed the oppressiveness of organized societal hierarchies, totally encompassing my own age-appropriate defiance of authority," Baker writes. "The list went on and on."

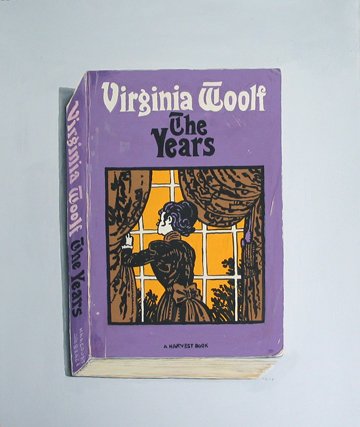

"As my involvement with this act of 'portraiture' has continued," Baker writes, "the reasons for choosing which titles and editions have evolved and become more various, though it remains of paramount importance that they be familiar and of no special pedigree. In the end, these paintings stand against loss and for reverie, memory, optimism, desire, and love."

Baker says it took anywhere from one to three weeks to complete each 12 x 10 1/2–inch gouache portrait. But that doesn’t account for the time spent “fishing the used bookstores in search of the right thing,” he says: “no precious first editions, no rare things—just your common companions.”

Baker notes that he doesn’t use the Internet to track down books because it “goes against the grain” of the project, which he says is “a kind of fundamental social intercourse.”