I am taking a break from writing this summer,” says the writer Jenn Shapland. Having spent the last decade completing a doctorate, writing two rigorously personal and intensely researched books, moving to a new state, and holding down work outside her writing career, this is a well-earned break. Shapland’s second book, Thin Skin, will be published by Pantheon Books in August. This collection of personal yet outwardly reflective essays about interdependence, consumerism, and American history is a natural progression from Shapland’s first book, the celebrated and critically acclaimed My Autobiography of Carson McCullers (Tin House). The National Book Award–nominated work of creative nonfiction about queerness, legacy, and erasure, which uses the genres of biography and literary criticism as a springboard for memoir and self-reflection, was published in February 2020, just before the United States went into lockdown because of COVID-19. Thin Skin launches during a summer of ongoing climate crisis, a topic never far from Shapland’s mind or her writing.

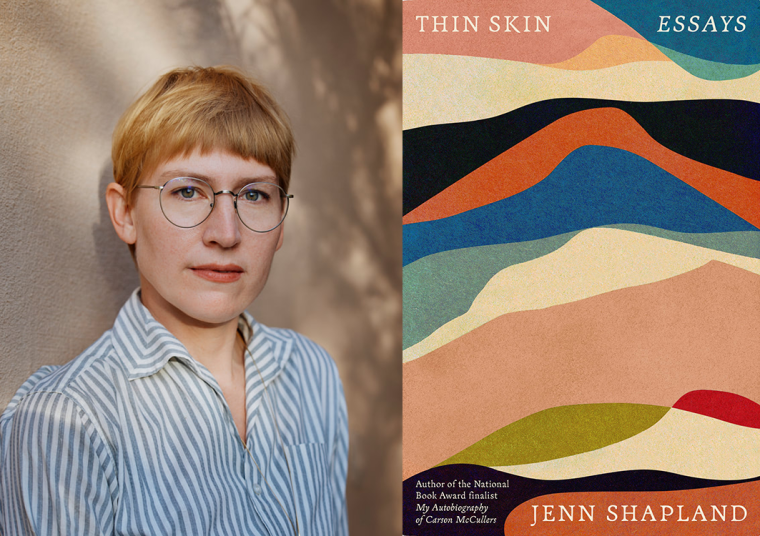

Jenn Shapland, author of the new essay collection Thin Skin (Pantheon, 2023). (Credit: Brad Trone)

The gravity of her subjects helps Shapland see past capitalist cultural insistence on the grind, the exhaustions of constant productivity and social media saturation: You can’t tackle enormous issues in a state of fight or flight. For Shapland, the question of environmental ruin echoes in her examination of her own fragile health, which is compounded by an awareness of public health—an expansive topic that shows up in her work in considerations of topics from isolation and scarcity to mass-market consumerism. In her interrogation of these topics, as well subjects such as the necessity of community and the need to embrace queerness as an expression of freedom, Shapland finds insight through her nimble and voracious sensibility as a cultural critic and her deft interviews with subjects as much as her self-examinations. “Jenn has a remarkable way of taking themes and questions and issues that are coursing through our world, that I think many people grapple with, and pushing our thinking on them to places we didn’t know it could go,” says her editor at Pantheon Books, Naomi Gibbs. “Her writing is so warm on the page even as she’s an intellectual dynamo. And when we spoke on Zoom, in the context of me pursuing the book, she was exactly that—so kind and open and also just so clearly, utterly, brilliant. I’m not sure you always get that—such sophisticated cultural criticism and thought with a truly warm voice and person.” Her friend the writer Darcey Steinke shares Gibbs’s admiration for Shapland’s unique talent: “I love how much she’s present in her work. It’s very discursive and you see how she’s thinking. She moves from idea to idea in a way that you wouldn’t necessarily anticipate she’d go to, but you’re thrilled she got there.”

To create such lucid and rigorous work with an open heart demands a clear, calm mind. Shapland is a writer who aspires to be as comfortable at rest as she is at work. At home in Santa Fe, where she lives with her partner, the writer Chelsea Weathers, Shapland e-mails, “I love spending time in the garden and watching the bees.” After years spent growing vegetables despite the challenges of the New Mexican desert geography, she’s pivoted. “I was talking with my friend [the artist] Eliza Naranjo-Morse the other day about gardening, and how we both came to growing flowers unexpectedly, having grown vegetables first. She said that growing flowers taught her that they feed and nourish people in a different way than food.” Her reflection sparks a connection between World War II victory gardens and the retreat to gardening that many forged during the pandemic. Shapland refers to the work as “necessary,” a nourishment as beneficial as stepping away from the phone or computer.

Her sentiments also harken back to the refrain “Give us bread, but give us roses, too,” which has variously been attributed to strikers, suffragettes, and poets alike. It’s an ethos that her friends recognize clearly in her work as well. Steinke recalls meeting Shapland and Weathers through a commissioned writing project on the groundbreaking abstract painter Agnes Martin. After traveling to New Mexico from her home in Brooklyn, New York, to visit Martin’s studio and archive, the three “connected over a love of art.” Over dinner at home with the couple, Steinke was struck by a quality of Shapland’s she calls “Gnomecore”: a desire to live at a slower pace, make a cozy home, value your partner, and create a lovely, charming life at home. This collected self-possession offers Shapland more than just a quaint sensibility. It creates spaciousness in her life and work.

As Shapland sets aside writing for the summer, she’s embarking on a different project: beekeeping. Her friend the poet Jenny George describes the care with which she’s taken on this new labor. George says Shapland “has spent a year teaching herself beekeeping, researching, and planning, and now she’s diving in—ready to give her full attention to this new responsibility. Those are lucky bees, to be part of Jenn’s careful and attentive work.”

It’s a project not without its challenges. “I’m learning as I go, which is also how I approach writing,” says Shapland. “At first I got worried about the bees, because they seemed sluggish, and I found a bunch of dead bees outside the hive. I called the plant nursery behind our house and asked if they use any pesticides on their plants. The person who answered said, ‘No,’ and immediately hung up, which I find…suspicious. So, you can see I’m still living in the questions of Thin Skin.” These questions surface from the jump in Shapland’s new collection. In the book’s preface, Shapland talks about her dermatological diagnosis as someone with actual “thin skin,” a condition created by the fact that the ceramide layer of her skin, “what keeps the bad stuff out and holds moisture in, is more like a lazy macrame” on her. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic began, Shapland masked outside her home in order to escape migraines triggered by pollen.

Her extreme sensitivity to the environment was a launching point to “question the idea of myself as a being in need of protection, indeed as someone who could be protected.” The more Shapland researched, the more she saw that avoiding environmental contamination was impossible. She writes that “instead of feeling fear, loss, sadness, anger, I try to understand it. I research it. I seek to learn its roots and causes. But learning and knowing and thinking are not modes of healing, repair.” These actions may not perform the work of healing or repair, but they open a discussion. Thin Skin is a necessary series of conversations about challenging topics, including Indigenous culture, privilege, friendship, the desire for space and a creative life, the choice to not raise children, and reconciling with death while choosing to live the life of dreams you haven’t even fully imagined.

Though her work occupies the landscape of personal essay, Shapland digs well beyond her own experience for answers. The book showcases dense research on nuclear contamination and makes entwined literary references to Octavia Butler and Silvia Federici, Paul Lisicky and Tressie McMillan Cottom, and Rachel Carson and Eula Biss. Additionally, her use of oral history in the book’s first essay, “Thin Skin,” moves her own experience to the margins, prioritizing the voices of Indigenous activists and artists in New Mexico whose community has been ransacked by American expansion and the development and aftermath of a national nuclear program. Moving the essay’s center from herself to others is an act that speaks to the permeability of community. Shapland sees and honors the ways in which we are all subjects who cannot escape the impact we have on one another.

Considering her backyard, Shapland notes that not all of her bees have thrived in their new home. “After finding dead bees, I read that a hundred bees will die every day, as they only live about six weeks. Each morning, worker bees carry out the dead or dying bees, leaving them on the porch or pushing them over the edge. I’m full of bee facts, lately, a walking bee encyclopedia. I’m an Aquarius, so sharing esoteric facts is my love language. My friend Jenifer, who is teaching me about beekeeping, said to me the other day, ‘maybe it’s time for you to stop reading.’ Sometimes this is good advice for me.”

This tension between rigor and fluidity surfaces as a constant in her life. In correspondence, Shapland shares her current reading (“I read different things at different times of day, always in the middle of a number of books”) which is a riotously eclectic mixture of poetry, fiction, and essays she’s been prompted to read because of a lecture, a film, or a friend (“the very best thing I’ve read in a long time was sent to me by Darcey Steinke, it’s called Proverbs of a She-Dandy by Lisa Robertson”). Summer is a time of rereading for her, so Shapland is tackling Joy Williams’ The Quick and the Dead “for maybe the third time,” but is also nursing a yen to reread Wuthering Heights and Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, both inspired by rereading Mary Ruefle’s Madness, Rack, and Honey. Different rooms offer different books; books on beekeeping keep company with volumes of poetry by Tove Ditlevson on the kitchen table. Shapland’s reading life is a blissful, endless seminar.

The texture of Shapland’s voracious reading was engrained at a young age. After growing up a reader in Illinois, her love of books crystalized in college, when she focused on literary studies at Middlebury College in Vermont. “I had to learn multiple languages, and read a list of books that started with ancient Chinese and Greek texts, classics, and then it worked its way up to 1922 and Ulysses.” Despite the thrilling proposition of such an expansive list, the list was in no way inclusive. “It was amazing, having this classical literary education, but then at the same time, there were very few women on the list and very few people of color on the list.” Shapland was also struck that the list closed at Modernism, a shortcoming in her education that helped lead her to graduate school to pursue a doctorate in English at the University of Texas at Austin in 2010.

“When I decided to apply for grad school [in 2009], it came out of a place of wanting some sort of job security, thinking, very naively, that getting a PhD in English would ensure that I could have a job as a tenure track professor somewhere and I could kind of spend my life immersed in books and writing. And so it was, to my mind, a practical decision, which is hilarious,” says Shapland. Increasingly, graduate school is no longer a secure career path. For the fortunate, it’s a place to ask questions and find your voice. Shapland recognized that, for her, academia wasn’t the place to flex her muscular devotion to books and writing. However, it did offer unexpected opportunities. As a bookseller at Austin’s renowned Book People bookstore, Shapland read widely. Her staff book recommendations (including Jo Ann Beard’s In Zanesville, Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch, and Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be) remain on file today.

In reaction to her classics-saturated college experience, Shapland sought out contemporary literature. “I was just trying to figure out what’s going on,” says Shapland, “reading the things that were big and being talked about like Zadie Smith and David Foster Wallace.” Shapland even began a book club among her graduate school peers to stay abreast of new books. “I need a multitude of sources of nourishment,” Shapland reflects, “I am saddest when I feel I have nothing to read. Which is a ridiculous feeling! But one that surfaces now and then. It lasts about a day, and then I’m back out foraging.” Her infectious appetite may have been too much for a graduate program where one’s concentration narrows over time rather than expanding. Academic writing didn’t “feel like a good fit.” Taking classes on documentary film and working in the Harry Ransom archives, Shapland began to make her own place as a polyglot.

Beyond the academy, opportunities surfaced. A turning point came with Shapland’s acceptance to the Tin House Writers Workshop, a summer writing conference held annually in Portland, Oregon. Lance Cleland, executive workshop director at Tin House, recalls, “I was first introduced to Jenn and her work in 2015 via her nonfiction application to that year’s summer workshop. Our selection committee was impressed with her ability to excavate the past, fusing what was clearly a tremendous amount of nuanced research with a pacing that felt almost novelistic at times. There was an emotional clarity to the work that felt direct without being cloying, offering the reader an emotional road map without having to give specific directions. That clarity was also found in her cover letter, which demonstrated an interest in fostering community while at the conference.” As an outgrowth of that community, Shapland wrote an essay for the literary magazine Tin House, titled “Finders, Keepers,” about her experiences at the Ransom Center, which was awarded a Pushcart Prize in 2017.

Shapland continued to seek out community through her writing and residencies. Throughout graduate school, she continuously wrote essays, but she also began work on what would become her first book, My Autobiography of Carson McCullers. Applying her ever persistent curiosity to the legacy and work of the late 20th-century writer Carson McCullers, Shapland created a hybrid work of cultural criticism, biography, and memoir that called to task conventional wisdom surrounding scholarship, brought exuberant dignity to McCullers’ life as a queer woman and provocative writer, and served as a coming-of-age tale for Shapland herself, who began to openly identify as a lesbian. It is a bold and crackling work that shines with intellectual and personal dexterity.

It is no small accomplishment for a debut nonfiction book published by an independent press to be named a finalist for the National Book Award. The success she enjoyed was a reflection of Shapland’s intense dedication to following her own path as a writer and scholar. Another polyglot writer (cookbook writer, cultural critic, and biographer) Sara B. Franklin describes My Autobiography of Carson McCullers as “a revisionist history crafted by way of daring and provocation.” She adds that, “Shapland understands that the question of looking for a subject’s essence is both more interesting and more true than attempting to assert a definitive, authoritative story of a life. Only by asking new, deeper questions can we resist oppressive narratives.”

Her agent, Bill Clegg, reflects, “I first read Jenn’s work when she sent me a draft of The Autobiography of Carson McCullers in 2017. I remember being struck by her voice on the page, which was so strong, so immediately clear and particular, and then, the deeper I got into the manuscript there was a fearlessness that made it obvious that she was creating something new and exciting. I remember there was someone else or several others who had offered to represent Jenn and being on the phone with her, standing on the street outside an apartment building in Tribeca, late for a dinner, trying to make a case to work with her.”

With so much buzz and hype surrounding her work, the siren call of prestigious adjunct teaching posts or a predictable cultural mecca like New York City could have been Shapland’s for the taking. Instead, despite a market that thrives upon exposure, Shapland keeps a low profile. Steinke puts it succinctly, “She has put writing at the very center of her life.” It was a choice that was set in 2016 when Shapland and Weathers left Austin for Santa Fe. “I was looking for quiet, for time and space to write and think, for fewer obligations,” she says. “And Chelsea and I were both looking for work outside an institutional or academic setting. We moved here without jobs, sort of on a whim, hoping it would work out. Neither of us wanted a ‘career,’ we just wanted to work enough to be able to live.”

It was a bold gamble that paid off for them. Unlike coastal cities, Santa Fe has offered space and an absence of pressure. It’s an artistic town that doesn’t respond to trends. Rather, its geography encourages one to slow down and pay attention. It takes time for desert life to grow. For someone more interested in raising vegetables than accumulating social media followers, this has made New Mexico a compelling alternative. In Santa Fe, Shapland also found part-time work that suited her needs. She writes in Thin Skin that “working twenty hours a week as an archivist for Bruce Nauman, a visual artist” has given her the freedom to think and write on her own terms.

The pace is also slower. “In Santa Fe, people leave each other alone,” Shapland notes. “I remember being shocked when I started making friends here, most of whom were in their 50s, 60s, or 70s, and they would say, ‘See you next month!’ or ‘See you in the spring!’ Whereas I was used to seeing people weekly, even nightly in Austin, which had a strong culture of hanging out. It’s really freeing to have friendships that are close and deep but not time-consuming.”

This deep appreciation for friendships informed by intellectual connection and genuine affection over a compulsive need for attention relates to the confidence and freedom Shapland has found in her identity as a queer person. “I feel so lucky that queerness has shaped my life,” she says. In the book’s final essay, Shapland talks about lesbian separatists from the 1970s and her own desire to live a life without bearing or raising children. Although she notes that these elders can be “super problematic,” she finds their determination to live unabashedly on their own terms appealing, particularly in the wake of the reversal of Roe v. Wade and in the face of contemporary backlash against the rights of queer and trans people. Like these women who believed in a different world, by picking up her roots and building a community on her terms, committing herself to a reflective life and forging a relationship without children, Shapland has shaped an artistic practice—and a life—that centers the same ideas of care so central to her work.

“This may be an unpopular opinion,” she posits, “but for me, literary communities exist in and through books, the written word. Communion, communal experience happens when you are reading a book and find some third space between your experience and the author’s that you inhabit together…silently…and alone. In what Mary Ruefle calls the margins, the place apart from active life. To me, that’s the most meaningful connection, community.”

Lauren LeBlanc is a writer and editor who has published in the New York Times Book Review, the Atlantic, Vanity Fair, and the Boston Globe, among others. She has worked at Knopf, Atlas & Co., Penguin Random House, Guernica, and the Brooklyn Book Festival. Born and raised in New Orleans, she lives in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and is an elected board member of the National Book Critics Circle.