I’m glad I have memories of sight,” writes Selena Tirey. “I can remember sprawling rural landscapes, the field of beans and corn across the road, and the goldenrod that returns every spring. I remember video games that were too hard, and the Christmas tree laden with gaudy ornaments rising from a sea of presents. I understand the concept of color, but now my vision is just a blur of light, moments of darkness that fade in and out, specks of gray flickering like a starry night.” Tirey, who is visually impaired, spent the first thirteen years of her life as a sighted person. Her personal essay, “How to Impersonate a Blind Person,” appears in We Can Hear You Just Fine: Clarifications From the Kentucky School for the Blind, a collection of essays by seven visually impaired teenage students in Louisville. It is the third and most recent book project from the Louisville Story Program, an organization dedicated to strengthening community and amplifying unheard voices by helping people tell their own stories.

I’m glad I have memories of sight,” writes Selena Tirey. “I can remember sprawling rural landscapes, the field of beans and corn across the road, and the goldenrod that returns every spring. I remember video games that were too hard, and the Christmas tree laden with gaudy ornaments rising from a sea of presents. I understand the concept of color, but now my vision is just a blur of light, moments of darkness that fade in and out, specks of gray flickering like a starry night.” Tirey, who is visually impaired, spent the first thirteen years of her life as a sighted person. Her personal essay, “How to Impersonate a Blind Person,” appears in We Can Hear You Just Fine: Clarifications From the Kentucky School for the Blind, a collection of essays by seven visually impaired teenage students in Louisville. It is the third and most recent book project from the Louisville Story Program, an organization dedicated to strengthening community and amplifying unheard voices by helping people tell their own stories.

Darcy Thompson, a former managing director of Teach for America, founded the program in 2013. Thompson was inspired to take action during a trip to New Orleans, where he discovered the Neighborhood Story Project, a collaborative ethnography and publishing organization helping people in the community share their stories. “Gosh, I would love to have this back home,” Thompson remembers thinking. So he consulted with a cofounder of the Neighborhood Story Project to establish a similar program in Louisville, with a focus on book projects. “People telling their own stories,” Thompson says. “That was key.”

For its first partnership, the Louisville Story Program worked with the Academy @ Shawnee, a magnet high school that serves many of the lowest-income neighborhoods in Louisville and has some of the highest student poverty rates and lowest test scores in the area. Eight high school juniors from the academy participated in the program’s summer workshop, through which they learned the craft of writing narrative nonfiction. (The students were paid for their participation.) The workshop led to the program’s publication of Our Shawnee, a collection of essays that interweaves students’ descriptions of some of the most impoverished neighborhoods in Louisville with personal narrative.

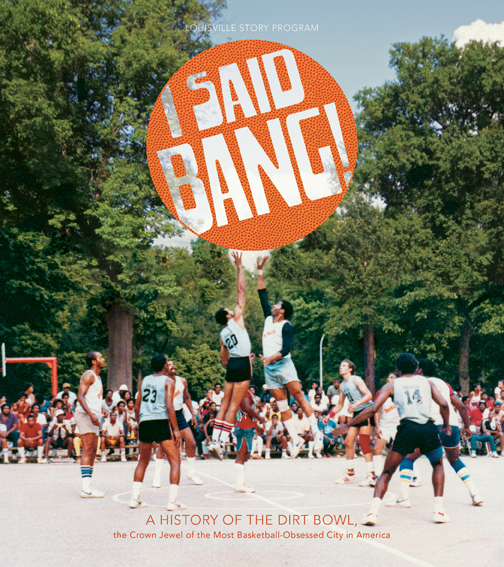

Thompson knew that he wanted the next project to have a different focus, so he turned to one of the city’s greatest passions: basketball. I Said Bang! A History of the Dirt Bowl, the Crown Jewel of the Most Basketball-Obsessed City in America, released in February 2016, collects archival photographs, personal essays, and interviews with organizers, players, spectators, announcers, referees, vendors, and coaches of the Dirt Bowl, a summer-long outdoor basketball tournament that has taken place every year in Louisville since 1969.

For We Can Hear You Just Fine, the program’s deputy director, Joe Manning, ran a writing workshop at the Kentucky School for the Blind, working with students four days a week during the 2015–2016 school year. The book, composed of those students’ stories, was published in November 2016. “All the chapters in some regard touch on visual impairment, but we had to be really careful to not just make it a book about being blind,” Manning says. “That was a struggle for me as editor and an instructor.”

One of the program’s next projects involves stories by people who work at Churchill Downs, the iconic track where the Kentucky Derby is held each year. “There are over a thousand people who work on the back side of the track—stable workers, exercise riders—but we don’t ever get to hear them talk. They’re sort of invisible,” says Thompson. He and Manning are running writing workshops and coordinating interviews and conversations with several of these workers, many of whom speak Spanish. The book that arises will likely have a strong bilingual component.

Giving people a platform to tell their stories is just the beginning of the program’s mission. “Once each book is out, we work really hard to leverage the success of the book into other opportunities for the authors,” says Thompson, noting that all contributors receive royalties for their work. By helping writers focus not just on craft, but also on developing practical skills such as editing, revising, and pitching, Thompson and Manning hope their students will continue to write polished stories and find new outlets for their work, long after the workshops have ended and the books have been released. One contributor to I Said Bang! recently worked with a local npr station to develop a radio documentary, and a contributor to We Can Hear You Just Fine is currently working on a podcast. “It’s a platitude that everyone has a story to tell,” Manning says. “Everyone has a story to tell, but you have to try really hard to make the story you tell compelling to a reader or a listener.”

Thompson is thrilled by the story program’s success thus far and is eager to expand within Louisville. But he also stresses that staying local and being attuned to a specific community’s needs are critical components of his mission. “I would never consider making a franchise in different cities,” he says. “This kind of work is done well by people who live in a community.” Ultimately, the Louisville Story Program is about giving people like Selena Tirey the opportunity to connect with their community, and for the community to share stories that might otherwise never emerge. “We need these stories,” Thompson says. “We need to hear voices like this.”

Adrienne Raphel is the author of What Was It For (Rescue Press, 2017) and But What Will We Do (Seattle Review, 2016). Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, Paris Review Daily, Poetry, Lana Turner Journal, Prelude, and elsewhere. She is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and a doctoral candidate at Harvard University.