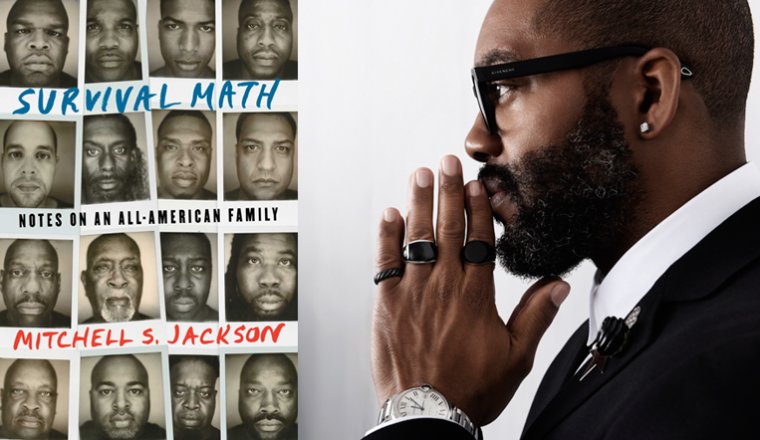

Readers were excited about Mitchell S. Jackson’s new memoir, Survival Math: Notes on an All-American Family, long before its publication this month by Scribner. Jackson’s first novel, The Residue Years (Bloomsbury, 2013), was a wonder of a book, as genuine, intelligent, and allusion-rich as a Kendrick Lamar song, an autobiographical novel that explored new territory (Who knew there were Black people in Portland?) and gave readers a voice they’d been waiting for. Jackson’s language sweats; it climbs across cultures, regions, and philosophies, and Survival Math furthers his investigation of his native Portland’s history—both real and imagined—along with the complexities of family, fatherhood, and America.

Survival Math: Notes on an All-American Family by Mitchell S. Jackson is out March 5 from Scribner.

“If you’ve read Mitchell S. Jackson, you already know he writes with a poet’s ear,” says National Book Award–winning poet Terrance Hayes in a pre-publication blurb for Survival Math. “His sentences radiate empathy. He perceives the lives of hustlers, prisoners, and ghosts. He speaks to and with and for his people—which is to say, your people and my people.” Novelist Angela Flournoy, meanwhile, calls the book “a compassionate meditation on the human costs of this country’s ongoing war on Black lives,” and writer D Watkins describes it as “a timely narrative that gives us a glimpse into the Black America we rarely encounter in mainstream.” These testimonials—along with other raves by Salman Rushdie, Jesmyn Ward, Jason Reynolds, and Tyehimba Jess, among many more—remind us of the need for such a book: a complex rendering of Black life in a literary landscape and a country where such narratives, like the voices of Black men themselves, are so often muffled, broadcast in only one dimension.

Jackson, who once sold drugs and spent time in prison, where he now leads workshops and talks for incarcerated youth and adults, describes Survival Math as a way of thinking about power and identity. The memoir is at once a meditation on Jackson’s own life and the men who shaped it, who all had to hustle to get by. Jackson describes these men and their hustles with empathy: More than acts of survival, he writes, hustling has its own set of ethics and challenges a system that often bases financial opportunities on one’s family name. Survival Math is marked by trauma but lacks self-pity: Jackson is hard on himself while his humor and compassion for others—his uncles, his friends, his ex-girlfriends, his mother and his daughter—expands the memoir, allowing the book to function as a communal story, larger and more radiant than any single voice or subject.

Jackson is a recipient of a Whiting Award and the Ernest J. Gaines Prize for Literary Excellence. He was also a finalist for the Center for Fiction’s Flaherty-Dunnan First Novel Prize, the PEN/Hemingway Award for First Fiction, and the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award, and has received fellowships from the Lannan Foundation, the Ford Foundation, TED, and New York Foundation for the Arts. Jackson received a master of arts in writing from Portland State University and an MFA from New York University, where he now teaches writing. He lives in New York City.

What do you hope people most get out of Survival Math?

What I’m most hoping for is to present an artful and rigorous and imaginative and candid account of what it has been like for my people. My people meaning my family, Black folks from my home city and state. And if I do that, I’d argue I’m also speaking to what’s happened to Black folks far and wide. But I also want the reader to feel my presence, to never forget that I’m the one who has told them these things, that the prose is being filtered by my consciousness, which is to say my literary voice. I’m of the mind that how someone says something is almost if not equal to what they say. In a perfect world, the reader would have a sense of encountering a work that’s singular, or in the least, something rare.

People go nuts over your language, its specificity and mastery, the way you intersperse histories (speeches from Frederick Douglass, a discussion of boxer Jack Johnson and the White Slave Act) and philosophies—from your Uncle Henry’s “fast ten, slow twenty” capitalist theory to French Philosopher Ernest Renan’s ideas about nationhood to your own description of the seemingly unattainable aspects of the American Dream—with language you hear on the corner. What effect do you want your language to achieve?

I’m always thinking how can I impress upon the reader that this is a particular experience. Some people feel beholden to standard English, to the rules of grammar and syntax, to a certain frequency of allusion, to tradition, etc. But I’m trying to shape the language to represent my experience, one that’s grounded in the oral tradition as much as the literary. There’s the part of me that knows the language in which I work was never meant for me, or was meant for me and mine as a means of oppression. Knowing that implores me to break the rules, to push against them, to invent new rules. For this reason, I love neologism and portmanteaus. I love hyperbole and onomatopoeia. I love anaphora and alliteration. I’m hyper aware of the sounds my sentences make. The language, though, must be in service of revealing my identity, how I see the world. For me, it’s not just language I hear on the corner; it’s the language I hear in my head and heart. It’s as close I’ll get to a native tongue.

I don’t want to ask this question but another Black woman reading this book may be wondering the same thing. You write with a lot of sensitivity about the women in your life—nearly breaking your neck to attend a father-daughter dance, your mom’s experiences with gendered racism—and you include e-mails from your exes, the women you cheated on. I thought that was courageous because some of the women were in a lot of pain, and they’re not easy on you. But part of me wondered—are you bragging about your penis, your ability to hurt women?

That’s a valid question. It’s something that I struggled with. It felt for a time that I was leaning in that direction, that I was somehow transmuting what I’d done into a kind of currency. Perceiving that happening gave me a great anxiety because that wasn’t the intent at all. Like, not at all. I’m sure there were a number of factors at play, but one of them was that I’d been used to framing what I’d done for other men who had similar values—my cohort or in some cases co-conspirators. But those former pathologies can’t hold up to scrutiny. I also determined that the most fitting thing to do was to add the perspectives of past partners. Their voices were not only important reminders of the harm that I’d caused, but also countered my perspective becoming a hegemony. I hope that what I wrote isn’t interpreted as bragging. The braggarts I know only mention the good parts. I hope there’s too much reflection on the consequences of my deeds [in the book] for someone to judge me as making light of them—or worse, valorizing them.

But you also talk about the importance of Black men showing respect to other Black men—these are conversations people could have more often. And your book isn’t all misery, all tragedy. There’s humor—you’re making jokes in crisis situations—and empathy too.

Yes, I do talk about Black men showing respect to other Black men. I think that might be our greatest currency, the sense of being respected. Dudes will go to great lengths to garner and protect their respect, to not be disrespected. There are plenty dudes doing significant time on account of protecting their respect. Some dudes I know would rather die than get “punked,” which translates to a blatant disrespect. I’m glad you also point out the levity in my work. My childhood was abundant with joy, love, happiness, play. Toni Morrison once said she writes characters that are “unavailable to pity.” She was talking about fiction but I take that as a mandate for all genres, as a personal challenge for my work. I don’t ever want to paint my family as downtrodden or me as mostly miserable. That wasn’t the case. In fact, happiness might’ve been the dominant emotion of my childhood, at least until my mother’s addiction became more apparent. Having done so many things that have demanded forgiveness, understanding, and empathy, I’ve felt compelled to reciprocate it. Humor, or an outlook that allowed me to laugh in spite of trials, has ushered me to the other side of more than my fair share of crucibles. It makes sense to imbue the work with it, to strive to be on the page, the most of who I am in the world.

How does your interest in social justice influence the book?

In truth, I didn’t have a sense of pursuing social justice while I was writing the book. Social justice is abstract to me. At least for the most part, which is why I’m always trying to ground my ideas in the personal. That said, I do find some terminology in social and criminal justice helpful in thinking about what I’m trying to do on the page. One such term is credible messenger, which is someone whose ethos is valued by incarcerated persons because they have like experience and trust their expertise. I want to instill in my readers the belief that I’m a credible messenger. I even explicitly ask for in some cases: Believemewhenitellyou. Trustandbelieve. What might’ve been most interesting to me while I was writing the book was history—and in particular, history as seen through the lens of post-colonialism. There are very few social problems for American Black folks that can’t be traced to the legacy of chattel slavery. The damage it has done might be everlasting.

So your language is trying to undo damage. What should readers understand about it?

I don’t know if I’m trying to undo the damage as much as reflect how my experiences have shaped me. Some of those experiences are damage for sure, but some of them are also love and care and creativity and other nourishments. I want my writing to be a form of jazz, meaning something grounded in rhythm and cadence but also art that creates the sense of freedom and also art that gives sense of something improvised. I think improvisation has great potential to excite a reader because they don’t know where it will go next. Speaking of jazz, it was Miles Davis who said, “You got to play a long time to play like yourself.” What I want my readers to say is, “Wow, this guy sounds like himself”—or in other words, like no one else. Maybe I haven’t been making my music long enough for that to be pure truth; however, sounding like myself is a prime ambition—the aim always.

Rochelle Spencer is the author of AfroSurrealism: The African Diaspora’s Surrealist Fiction (Routledge, 2019) and Guardian Angels (Nomadic Press, 2019) and the coeditor, with Jina Ortiz, of All About Skin: Short Fiction by Women of Color (University of Wisconsin Press, 2014).