It is early on a Friday morning when I meet Bulgarian writer Georgi Gospodinov and translator Angela Rodel, recipients of the 2023 International Booker Prize for the novel Time Shelter, at a Costa Coffee behind Sofia University in downtown Sofia, Bulgaria. Gospodinov, whose work has been translated into twenty-one languages and whose other prizes include the Jan Michalski Prize for Literature and the Angelus Central European Literature Award, both for his 2012 novel The Physics of Sorrow, takes off his summer coat to reveal a black T-shirt adorned with an image of a Pac-Man video game screen.

Georgi Gospodinov and translator Angela Rodel, recipients of the 2023 International Booker Prize for the novel Time Shelter, at a Costa Coffee behind Sofia University in downtown Sofia, Bulgaria. (Credit: Stephen Morison Jr.)

When it was announced in late May that Gospodinov’s third novel, translated into English by Rodel, had won the Booker—the first time a Bulgarian writer has received the honor—I was still on page 62. Time Shelter, which was published in Bulgaria by Janet 45 in 2020 and in the United States by Liveright in 2022, begins with a quirky premise. It is about a man who opens a retirement home in Switzerland for people with Alzheimer’s Disease. The rooms are thematically organized by decade, and he matches his patients with the decades they can still remember. Gospodinov is known for his unusual plot structures. The novel is largely a meditation on memory, and the lack of linearity kept me from getting a firm grasp for the first fifty pages or so. But I read steadily on, registering bemusement for a few pages and curiosity for a few others, until around page 50, when I realized I was no longer counting pages. The voice, the premise, and the humor had captured me, and I was along for the ride. Many of my favorite books begin this way. They tease me from behind a stilted narration or a labyrinthine plot for fifty or sixty pages until the unusual voice becomes a familiar guide.

Time Shelter is about the way things used to be, and also about the way we like to remember the way things used to be. It’s a story about old things, the flotsam and jetsam of the past, told in a way that I haven’t experienced before, and it’s this combination of oldness and newness that reminds me of so much of what I love about reading.

The novel fits neatly into Gospodinov’s body of work, which is possible to view as a sort of literary arthropod of chapters, stories, and prose poems. He began as a poet during the Eastern European economic chaos of the 1990s. His collection Lapidarium (1992) won Bulgaria’s National Debut Prize, and four years later, his next collection, The Cherry Tree of One People, won the Book of the Year award from the Bulgarian Writers’ Association. He released more poetry collections, including Letters to Gaustin (2003), which he references in Time Shelter, and his international breakthrough occurred with the 2005 translation of his 1999 novel, Natural Novel. Translated by Zornitsa Hristova for Dalkey Archive Press, the book leans heavily on metafiction and consists of linked stories that connect tangentially to tell the evolving story of a protagonist who shares the name of his author. Several chapters describing ideas for how to write a novel. One tangent revisits the toilet scene from Pulp Fiction. The book is similar to Time Shelter in tone and ideas, except—pulled from the bleak times that surrounded Gospodinov in Bulgaria in the 1990s—its humor is darker. Natural Novel was translated into over twenty languages and paved the way for Gospodinov’s next novel, The Physics of Sorrow (2012), which went on to be nominated for and win awards in multiple countries.

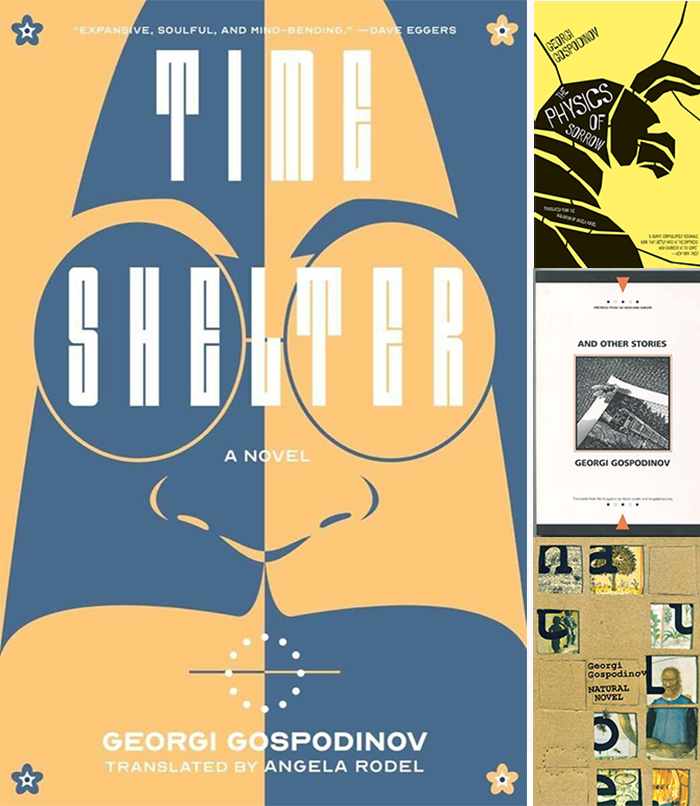

Gospidonov’s books include the novels Time Shelter (Liveright, 2022) , The Physics of Sorrow (Open Letter, 2015), and Natural Novel (Dalkey Archive Press, 2005), as well as the story collection And Other Stories (Northwestern University Press, 2007).Ultimately, Gospodinov is a satirist. He takes the piss out of cultures and countrymen, a bit like the great Bulgarian writer Aleko Konstantinov did at the end of the 19th century or Mark Twain did in the United States, except Gospodinov lacks the avuncular soft touch of these authors. His work is peppered with literary allusions and the interplay between his narrative and previous works is sharp and fun. I often catch myself snorting while reading a Gospodinov novel.

For the first fifty pages of Time Shelter, Gospodinov carefully and calmly skewers everybody, and then like the scientist touching his eye to the lens of the microscope and gently turning the knob, he focuses in on what he knows, which is Europe and Bulgaria.

Over drinks—tea for Gospodinov, coffee for Rodel, and lemonade for me—the author explains that his mother was a university student in Sofia when he was born in 1968, during a decade when the communist government encouraged young people to move to the cities. “It was one of the stupid socialist things, to urge people to the cities,” he says. “They needed workers.” Meanwhile, the children, including young Georgi, were sent to the villages to be raised by their grandparents.

Gospodinov spent his childhood in a village near Yambol, about three hundred kilometers east of Sofia. “I learned to read and write very early, from age five to six,” he says. “In the village with my grandparents, there were not so many children around.” He fondly recalls that his grandparents were great storytellers, however. “They would mix everyday things with magical things.”

I ask him if he remembers the first story he ever wrote, and he nods. “I had a nightmare that repeated every night. I tried to narrate it to my grandmother, but she said, ‘Don’t tell me or it will come true.’” In the nightmare, Gospodinov recalls, his family was in bottom of a well, and he was looking down from the top. In the dream he had avoided death, but now, standing at the top of the well, he was all alone. He felt abandoned. The dream clearly mirrored his feelings about being left in the village while his parents lived in the city.

Haunted by the nightmare, young Gospodinov confided in his grandmother, but she cautioned him that the nightmare was “full of blood,” and he must not talk about it. But it kept coming, night after night. Eventually, he had an idea: He would write down the story of the nightmare. “I took a notebook of my grandfather’s,” he says. “I wrote with early, big letters. First letters. And it worked.” He never had the dream again.

At around the same age he remembers reading his first books: Hans Christian Anderson’s fairy tale “The Little Match Girl” and “the best Bulgarian book ever,” Notes on a Bulgarian Uprising. Rodel, his translator, interrupts. “Really?” she says. “It’s unusual for a boy to read such a mature book.” The book by 19th century Bulgarian revolutionary, writer, and historian Zahari Stoyanov, about the April Uprising of 1876, an insurrection organized by Bulgarians in the Ottoman Empire, is usually introduced to high schoolers or college students.

“There was fighting and action scenes,” Gospodinov says, shrugging.

“On one side, there was a feeling of abandonment,” he continues. “That influenced The Physics of Sorrow.” In that novel, Gospodinov introduced the image of the Minotaur, the monstrous child of Pasiphae, Queen of Crete, and a white bull, who was kept locked in the Labyrinth, to represent his sense of abandonment.

“My Bulgarian therapist says she has lots of patients who work through that,” Rodel says.

Gospodinov describes life in a village far from the capital. He points out that his childhood home of Yambol once had its moment in the sun—years later he wrote his dissertation at Sofia University about how it had been a cradle of 20th-century philosophies like anarchism and futurism—but that was long ago. “It’s far from the center today,” he says.

He recalls a reading he gave years later in one of the smaller cities of Italy. He read from a part of The Physics of Sorrow that touched upon this sentiment of living on the margins, and after he was finished, people from the audience approached him and confessed that they shared his sense of being far from the action, far from the city, far from Rome and Milan.

“This is also how Bulgaria feels,” Gospodinov says, “this sense that life happens elsewhere, of not being part of life, that life doesn’t happen for us in Bulgaria.”

I ask Rodel about her childhood and she describes growing up in the suburbs of Minneapolis—not exactly a literary metropolis in the 1970s, perhaps, but not without resources. “We had an awesome public library,” she says. “I feel bad that my daughter doesn’t have that. You could go every week and get ten novels.”

In addition to being a prolific and award-winning translator of Bulgarian literature, Rodel is the executive director of the Bulgarian American Fulbright Commission. She earned a BA from Yale and an MA from UCLA in linguistics then came to Bulgaria in 1996 to study language and folk music. “Translating, like many good things in my life, I sort of fell into,” she says. Her first husband was a Bulgarian writer whom she met through her music studies, and Gosopodinov was his editor. As her Bulgarian improved, writers began approaching her. “’Oh, I’ve got this poem,’ they’d say. ‘Can you translate it?’” Nonprofits were looking for ways to connect writers and artists across Europe, and funds and prizes emerged to encourage translators and translations. Rodel started to realize that translating was a calling. She says she feels like she was in the right place at the right time.

I ask Gospodinov what it has been like bearing witness to the massive changes that have occurred in Bulgaria since the late 1960s. He spent his formative years under a strict communist regime with labor camps and school trips to visit Sofia’s Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum containing the embalmed body of the socialist leader who died in 1949. Gospodinov says he enjoys talking about this period. “All my novels are dedicated to everyday life during socialism. Every morning, my father and brother and I, we went to the cantina….” He glances at Rodel as he searches for the right word.

“The cafeteria?” Rodel offers.

“There was a blue plate on the wall with a message on it,” he says. “‘Writers are like surgeons for the human soul. They should cut out everything that is rotten and decayed.’” He smiles at the memory. “In between every spoonful,” he says, miming the act of dipping his spoon into a bowl and reading and rereading that prescription for writers.

“Austerity was an element of socialism,” he continues. He describes his parents’ simple basement flat in the city. “From the window, you could only watch the legs of the people passing, and the cats. We learned to live with deficits: lack of electricity, lack of freedom, a deficit of colors; everything was gray, the world was black and white. In school I was never asked about love or what rock music I liked.”

Gospodinov describes a divided world, one split between the socialist fictions that dominated the public sphere. In public life, he says, everybody pretended to be a “good citizen,” an “upstanding Soviet.” School was a place where you learned what you were supposed to say. “When the teachers asked what countries you liked, you said: Russia and the Soviet Union,” but in private, “you told your friends: Italy, USA, Germany, Greece!”

After high school he did two years of mandatory army duty then went to Sofia to study at the university across the street from where we are meeting. The year was 1989: The wall fell and communist rule ended. “We spent all the days in the street. I was twenty-one. We were so enthusiastic. We thought Bulgaria would become a normal country in a few months.” He laughs at his youthful optimism. Instead of quickly developing a functioning democracy and a healthy capitalist economy, Bulgaria, like many of the countries of the former Eastern Bloc, imploded. Members of the socialist ruling classes divided up the national industries and transformed into mafia dons and oligarchs. The economy splintered, inflation overwhelmed salaries, and governments leapt into power then just as quickly dissolved. Corruption was rampant.

Gospodinov has witnessed “thirty years of constantly going back and forth to the streets,” of seemingly endless rounds of efforts to curb corruption and inflation. Thankfully, since Bulgaria’s acceptance into the European Union in 2007, improvements have been made, and the last decade has seen steady economic growth and relative political stability.

Our conversation returns to Gospodinov’s award-winning Time Shelter. I tell him that the book hooked me once I recognized that its structure was less a traditional narrative than it was a meditation. I compare it to Melville’s Moby-Dick, with its slender central narrative that permits a meditation on the physical and metaphorical pursuit of a whale. Time Shelter’s structure reminds me of that, I say, except the central focus is memory.

“Obsession over memory,” Gospodinov says in agreement. “Yes, this is the obsession. I’m not interested in hard-boiled novels, not interested in who is the killer.” He shakes his head, but I’m not sure how he intends the gesture because in Bulgaria one shakes the chin side-to-side for yes and up-and-down for no. But he smiles and elaborates, “Well, time is the killer, of course.”

We laugh, and he continues. “I like the idea of a book as a place you enter, like a laboratory, to try your idea. I don’t have microscopes…. Language is the only tool.”

I ask him about the way his work makes reference to the Greek epics, the American canon, to Western European writers and Eastern Europeans both inside and outside Bulgaria.

“I like to write books that talk with other books,” he says. “It’s a network. There’s Odysseus coming back home, Moby-Dick is referenced by the epigraph at the beginning, The Magic Mountain is in there, pop culture references, Auden’s ‘September 1, 1939.’ It’s a book about Alzheimer’s and memory loss, memory dissolving while the world is ending…but the narrator will die first. This was my structure: The end of time, but as they say in the Bible, the end of time, not the end of place.”

Gospodinov’s reference reminds me that there were many times when I was reading his book that I wondered how hard it must have been for Rodel to identify Biblical and other literary references while she was translating. It is one thing to be fluent in a language, but it is another to recognize references to books that have been translated into Bulgarian from other languages.

“Having been raised very Catholic, Biblical references don’t escape me,” Rodel says. “But the Bulgarian [literary] references are harder. I worked with Georgi to identify them.” In The Physics of Sorrow, which she also translated into English, she remembers there was an unusual reference to an erotic passage from Mario Puzo’s 1969 crime novel, The Godfather. The passage had been well known to Gospodinov’s generation because erotica had been so heavily censored during socialist times. “Another deficit,” Gospodinov notes.

When an erotic scene was included in the translation of The Godfather, it quickly became infamous. Gospodinov knew that Bulgarians would remember it when he referenced it in his 2012 novel. He laughs and explains that, when his novel was translated into Spanish, he learned that censorship of erotic scenes had been even stricter under Franco’s fascist regime in Spain. The erotic scene from The Godfather had been completely excised. “So the translation of my book was the intro of the scene to Spain.”

While reading Time Shelter, I had been intrigued by certain specific words. I ask the pair about Rodel’s use of “diddly squat,” which is the English phrase she presents when the narrator hears an antiquated word that reminds him of a particular moment from his past. “It was very important,” Gospodinov says. “It was like the madeleine from Proust, an unlocker of memory, a thing that brought me back to the 1980s.”

I point out that, a few paragraphs after “diddly squat,” the word lumbersexual is used, and Gospodinov smiles and says that, while he thinks the translation is accurate, it is impossible for the English word to convey the secondary meaning that it does in Bulgaria. He explains that the current dark-bearded fashion looks very much like the hair and beard styles that were popular during the period in which Bulgarians successfully freed themselves from the Ottoman Empire at the tail end of the 19th century. In particular, Hristo Botev, a much-revered patriot and poet who was killed in close battle with the Turks, kept his hair combed in handsome waves, his mustache ends waxed into points, and his beard brushed full and lush. He would have fit right in at one of the many hipster barbershops currently scattered throughout Sofia.

“Humor, irony, and self-irony are very important to me,” Gospodinov says. “It’s typical of my grandparents’ sense of humor; the realization that we’re not in the center, that the world is elsewhere. Here in Bulgaria, we knew how to be pathetic, how to be too macho.” He appreciates how self-deprecating humor can negate ego. “It’s not intentional, but all my books have this mix between melancholy and humor.”

He returns to memories from his childhood and remembers an exchange with his great-grandmother when he was very young. “My great-grandmother was ninety-something when I was four, and I had a pain in my ears. I told her that I thought I would die, but she told me: ‘No, first, I will die, then your grandparents will die, then your parents, and then you.’ I began to cry louder.” He laughs. “But this is the Bulgarian way.”

Stephen Morison Jr. has been a contributor to Poets & Writers Magazine since 1999.