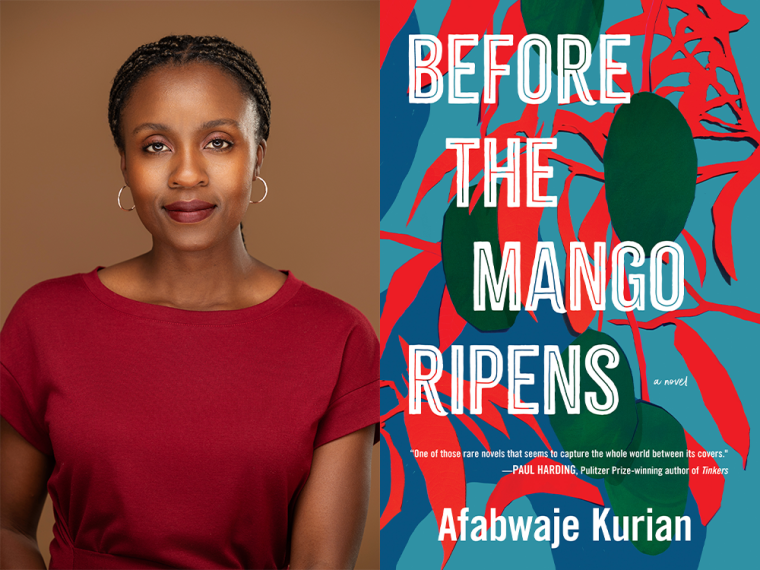

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Afabwaje Kurian, whose debut novel, Before the Mango Ripens, is out today from Dzanc Books. The novel, which is set against the backdrop of 1970s Nigeria, follows three characters in Rabata: Jummai, a beautiful and assuming house girl whose dreams of escaping her home life are disrupted by an unexpected pregnancy; Tebeya, an ambitious Dublin-educated doctor who returns to her small hometown and discovers a painful betrayal; and Zanya, a young translator who finds himself embroiled in a fight against the American reverend for the heart of the church and town. Pulitzer Prize–winning author Paul Harding calls Before the Mango Ripens “one of those rare novels that seems to capture the whole world between its covers.” Afabwaje Kurian received her MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Her short fiction has been published in McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, Callaloo, Crazyhorse, and Joyland, among others. She has taught creative writing at the University of Iowa and received residencies and fellowships from Ucross, Vermont Studio Center, and Ragdale. Born in Jos, Nigeria, and raised in Maryland and Ohio, Afabwaje divides her time between Washington, D.C., and the Midwest.

Afabwaje Kurian, author of Before the Mango Ripens. (Credit: Jaimy Ellis)

1. How long did it take you to write Before the Mango Ripens?

The seed for the novel began as a short story in 2014, so technically it took ten years to complete the book. But if I am to be more exacting, I like to say it took seven years from the time I locked into the heart of the novel to its publication. The characters that came to me first were Zanya, the novel’s protagonist; Nami, the woman Zanya courts; Jummai, a domestic worker; and Mama Bintu, the matriarch of the wealthiest family in Rabata. When the voice of Katherine Parson, one of the American missionaries, finally came to me in the summer of 2017, the novel crystallized in that moment. I knew I wanted to interweave the perspectives of the American missionaries and the Nigerian locals—thereby illuminating the racial, cultural, and religious tensions that would unfold in Rabata.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The research was one of the challenging aspects of writing this novel. I needed to conduct archival research, synthesize that body of work with personal interviews, and discern how best to deploy only a small fraction of what I learned in a manner that would not read as didactic. I conducted several interviews with relatives who grew up in Nigeria in the seventies and with missionaries who worked overseas. I read personal and primary-source correspondence, including the letters of a nurse with the Africa Inland Mission and memoirs from a missionary family that spent three decades in Nigeria. I read research articles about laborers, mission organizations, and government takeovers. I also had access to secondary sources that were given to me by relatives when I visited Nigeria, such as An Introduction to the History of SIM/ECWA in Nigeria 1893–1993 by Yusufu Turaki, The Gbagyi Journal, and Gbagyi Folktales and Myths by Joseph A. Shekwo.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Ninety-nine percent of the time, you’ll find me writing at home, on my couch or at my desk. I have regular, aspirational visions of myself heading out to a coffee shop in the morning, sitting near a window with an espresso and croissant at hand. But the reality is that I’m not a coffee drinker, and I typically prefer silence and the comfort of my home when writing. I also feel paranoia about leaving my laptop unattended in a coffee shop if I’m in need of a bathroom break! I tend to work from the mid-mornings and end before three in the afternoon. If I’m excited about a particular scene or have energy around a chapter, then I’ll write into the evening. Writing daily is dependent on what stage I’m in with a manuscript. For example, if I’m in the early stages, then I often have a daily word-count goal I must meet for several months. If I’m in a revision stage, then I’m doing far less word accumulation at that point. There are sometimes weeks when I’m ironing out a plot issue, for example, and the only thing I can do to forge ahead is read until my mind works out that particular problem.

4. What are you reading right now?

Uche Okonkwo’s A Kind of Madness (Tin House, 2024), Malcolm Gladwell’s David and Goliath (Back Bay Books, 2015), and the Book of Philippians.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Gayl Jones. She’s the author of Corregidora (Beacon Press, 1987) and several other works. She was a contemporary to Raymond Carver. I know Carver is praised for his minimalist prose and colloquial style—though many would attribute his voice to his editor, Gordon Lish. When I read Corregidora, I had the same impression of Jones’s literary style, and I was drawn in by the weighty matters of slavery, sexual violence, and trauma that the novel deftly addressed.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

It depends on the needs of an individual and what they’re looking to develop with their craft. I had an incredibly productive and valuable MFA experience. It gave me space to write and further discover my voice. It put me in an environment with writers who were dedicated to their craft, and it was highly motivating to be around that energy. An MFA can also expand opportunities for fellowships, grants, or residencies—if this is what you’re interested in. I do not think an MFA is essential to honing your voice as a writer or finding writing success, however one chooses to define that for themselves. There are opportunities outside an MFA to create a writing community: Take creative writing courses, submit to literary journals, attend conferences, etc.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

When we went on submission, I asked my agent when I’d hear back from publishers or how long it would take for the book to find its home, and she simply said, “You never know.” And it’s definitely been a “You never know” experience. I wanted specificity, and she smartly could not and did not promise it to me. As writers, we will have incomparable individual journeys, and we can’t fully know what surprises, disappointments, and joys await us.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Before the Mango Ripens, what would you say?

Keep writing until you have the entire novel—or at least most of it—out of your system, before you revise. I know there are essentially two views to the timing of revision—as you discover the novel, or after you’ve completed it. There are authors who revise as they write, and those who wait until a full draft is on the page before ever making an edit. My allegiance, based on my fits, starts, and experiences to date, is with the latter approach. I find that revision disengages you from the momentum of creativity when you’re first trying to understand what a story is about. It’s beneficial to refrain from critiquing or revising some of the words on the page, because you don’t yet know how fruitful they could prove to be.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Before the Mango Ripens?

Besides the primary and secondary source research I previously mentioned, my travels throughout central Nigeria in 2015 were also essential, when I interviewed a number of my relatives for the novel. Additionally, I read craft books such as Word Painting: A Guide to Writing More Descriptively (Writer’s Digest Books, 2000) by Rebecca McClanahan, and multi-voiced novels to help me better craft the novel’s structure since I was working with a large cast of characters.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

When I worked a nine-to-five and was bemoaning the fact that writing was not a more central pursuit in my life, I received advice from a mentor that propelled me toward the path I’m on now. He told me to take one year to do as much as I could that was writing-related—craft short stories, apply to conferences, enroll in writing workshops, submit to contests—and to see what doors of opportunity would open from there. I think there are times in life when people come along and grant us permission to walk a path that was always available to us to walk, and we were wholly blinded to it for whatever reason. I would give this advice to anyone who is languishing and feels like there’s something more they’re called to do: Take a year, pursue it, and see what happens.