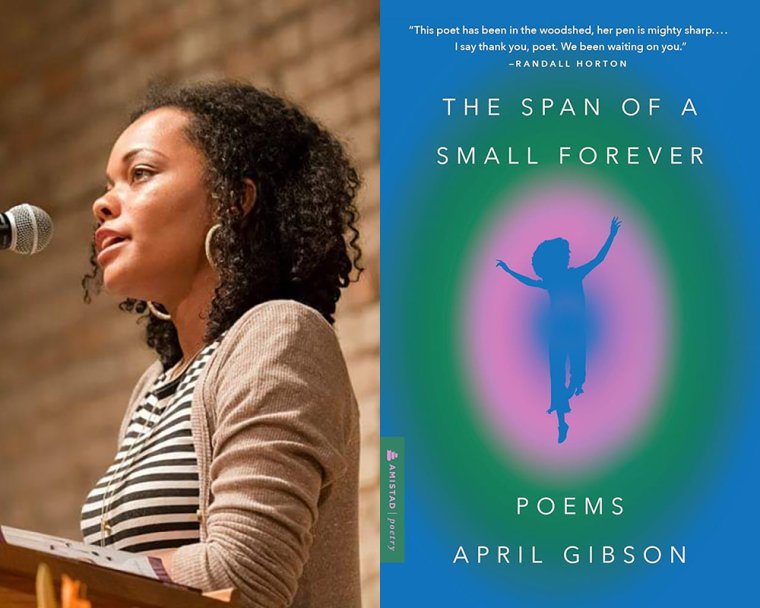

This week’s Ten Questions features April Gibson, whose debut poetry collection, The Span of a Small Forever, is out today from Amistad. In this mix of lyrics, prose poems, forms, and experimental poetics, such as erasure, Gibson considers chronic illness, child-rearing, spirituality, and the trials and triumphs of Black womanhood. In language that is by turns meditative, elegiac, and enraged, the poems confront the speaker’s long battle with poor health and a toxic medical establishment that brings as much pain as it relieves, as she recounts in “Misdiagnosed.” Yet the poems make space to celebrate, as in “An Awkward Ode to My Awesome Stoma,” a musical praise song for “my fishing hook / emptying pink mess / pulled through flesh / my Jesus side wound / my Sisyphus.” Sisyphean exhaustion is a prominent theme, both physical and emotional, particularly when it comes to enduring microaggressions and social violence; a fatigue that ultimately boils over in “The Black Woman Press Conference,” a section of the book in which the speaker pulls no punches in naming injustices, calling out perpetrators, and enumerating unabashed desires: “nothing can stop this flowering.” Memories of childhood mingle with later reflections on motherhood to poignant effect, capping off the collection with an epilogue in the voice of the speaker’s son, who “tells me how the world began.” April Gibson is a poet, writer, and professor from the South Side of Chicago. A winner of the Gwendolyn Brooks Poetry Award, a Sustainable Arts Foundation Award, and a Loft Literary Center Mentor Series Award in Poetry, she teaches in the Department of English, Literature, and Speech at Malcolm X College in Chicago. Her work has appeared in the Kenyon Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, Prairie Schooner, and elsewhere.

April Gibson, author of The Span of a Small Forever. (Credit: Min Enterprises Photography)

1. How long did it take you to write The Span of a Small Forever?

It took about ten years to write.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Time, patience, and distance. Time to actually write. Time to be patient with myself and my process. Some things cannot be created until other things are left behind. Time to distance myself from some of the realities beneath the poems. Time to reflect on who I was and who I was no longer. Time to let those versions of myself grow into their own stories, for the narrative to move from personal to collective, from catharsis to art.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

It really depends and has changed a lot over the years. When my children were younger I often wrote very late at night, after they were asleep and into the early hours of the morning. Now they are young adults, and I am a much older adult who needs to go to bed before midnight, so I often write on the weekends, especially Sundays because it’s my most peaceful day. Also, I teach full-time, and we all know how hard it is to write and teach. Needless to say, there may be some inconsistencies in generating work, but I always forgive myself. When I do write, be it intentionally or by a stroke of inspiration, I’m not generally at a desk. I may be propped up in bed with a million pillows, in the corner of my couch, outside on a porch, on rocks at the lake, or just about any place that does not make me feel like I’m “working.” And for some odd reason every time I am on a plane I am inspired to furiously write. I should take more flights, I suppose.

4. What are you reading right now?

Too many books at once. What’s sitting on my random reading pile right now? All About Love by bell hooks, American Precariat: Parable of Exclusion edited by Zeke Caligiuri et al, A Little Bump in the Earth by Tyree Daye, More Than Meat and Raiment by Angela Jackson, Feelin by Bettina Judd, and so many books I promise I will get to soon.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

The book is organized in sections, and the sections hold the poems in a way that is threaded by a theme or driven by a thematic emotional core, which, at least for me, is generally expressed in the section titles. The order offers readers a flow that starts with a kind of origin and carries out to an almost-end while offering a spectrum of feeling and reflection throughout that I hope shows a circling, a connection within and between sections.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

Leaving aside the discussions about student loan debt (which is a serious concern), I simply don’t think it’s essential for every aspiring writer to pursue an MFA. It really depends on their larger goals, their motivation, their life experiences, and a plethora of other factors. What I miss most about being in an MFA program is the dedicated time I gave my writing and having a consistent writing community. Because even after you have learned a great deal about craft, MFA or not, you will still need time and the right people around you (and to always read, read, read!). If writers can find or create those things outside of an MFA, they are heading in the right direction.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of The Span of a Small Forever?

Finding connections in my own work that I did not intentionally place there. I’d notice how pieces years apart would be in conversation. I also noticed how I was evolving the same conversation with myself over time. I would have these aha moments as I was putting the collection together, especially when organizing where poems would go, and I’d be amazed at how one piece fit so neatly with another, followed by my audible “Hmm” or “Yes!”

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The Span of a Small Forever, what would you say?

Take as long as you need. You’ll know when it’s time, and you’ll be glad you waited.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

The hardest part of writing this book was working to make more time. I had to do the work of teaching, parenting, and taking care of my health while completing this book, so I had to be creative with time and resources. One thing I did was work to secure fellowships and residences so I’d have designated writing space and time. And like many writers I conducted research for this book, from learning medical terminology to double-checking historical events and making sure I’d learned the proper names of products or items, since I name them throughout my work. But due to time constraints, I’d have to come up with creative ways to acquire information related to topics in the book, like asking my doctors a million medical questions and studying their after-visit notes, since I spent an excessive amount of time at the hospital. I also involved my sons in my work to reduce the strain and stress of being a writer and a parent. In some ways my children became part of the team. More than anything I had to talk to people—not in a formal-interview way but to just converse with folks, from my grandparents and parents to siblings and friends. So much of my writing is rooted in memory, and memory is tricky; it’s not right or wrong, but it can be singular sometimes. I wanted to bring in more collective memory, even if I was writing mostly in first person. I wanted that perspective to be informed in a more nuanced way. It could be as simple as asking someone, “Do you remember that time when...?”

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

So much good advice on how to write has been shared with me. Once, over a decade ago, I shared a poem that used a reference that was from African American culture, and the mostly white participants expressed confusion, which led to the premature conclusion that my reference should be removed. But there was one person—the only other Black woman in the workshop, I think—who knew with ease and appreciation exactly what I meant. The facilitator, who was also a Black woman, told me: So long as the people it’s meant for understand, don’t take it out. I forgot about that until now. But I realize it was about a practice of having agency and controlling your own narrative.