This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Aria Aber, whose debut novel, Good Girl, is out today from Hogarth. Set in Berlin’s artistic underground, where techno and drugs fill warehouses, the book follows nineteen-year-old Nila, the daughter of Afghan refugees, on her year of self-discovery. Raised in public housing graffitied with swastikas in Germany, and drawn to philosophy, photography, and sex, Nila has spent her adolescence disappointing her family while trying to find her voice as a young woman and artist. Nila meets Marlowe, an American writer who opens her eyes to a life of personal and artistic freedom. But as time goes on, Nila finds herself pulled into Marlowe’s controlling orbit, and racial tensions begin to roil Germany as well as Nila’s family and community. Garth Greenwell called Good Girl “a novel of overwhelming and conflicted love—for persons, for histories, for artistic creation, for Berlin.” He adds, “[Aber’s] poet’s eye makes a thermal map of emotional landscapes, lighting up passion, desire, desperate hope, and violence, and showing how difficult they can be to distinguish in the crucible of experience. Rarely has the wildness and bewilderment of youth been conveyed with such richly textured heat.” Aria Aber was born and raised in Germany and now lives in the United States. Her debut poetry collection, Hard Damage, won the Prairie Schooner Book Prize and a Whiting Award. She is a former Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford and graduate student at USC, and her writing has appeared in the New Yorker, the New Republic, the Yale Review, Granta, and elsewhere. Raised speaking Farsi and German, she writes in her third language, English. She recently joined the faculty of the University of Vermont in Burlington as an assistant professor of creative writing and divides her time between Vermont and Brooklyn.

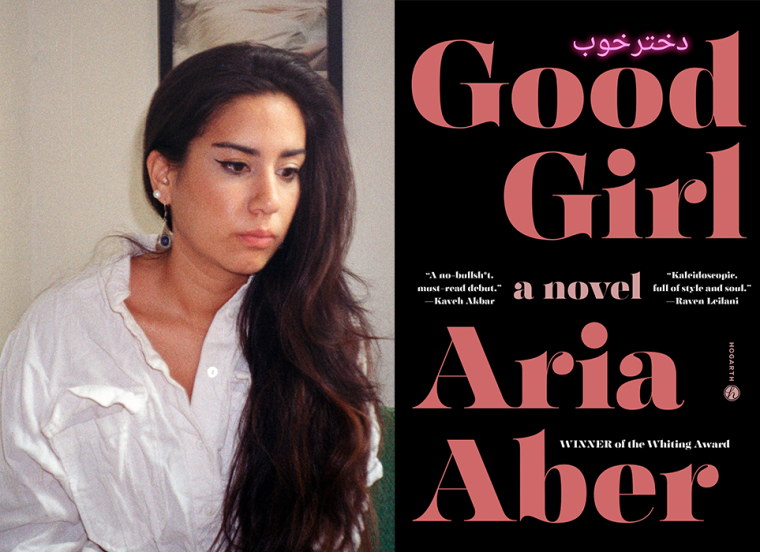

Aria Aber, author of Good Girl. (Credit: Natalie Aber)

1. How long did it take you to write Good Girl?

The earliest chapters of the book came to me in the spring of 2020, when I lived in Berlin and was going on long walks through my old neighborhood. Seeing the shuttered shopfronts, the closed clubs, the protests, and the rainy streets allowed me to re-inhabit the past through an almost surreal lens. A close friend of mine had just passed away, and this private grief, in combination with the great public grief of all the political upheaval that emerged during the pandemic, animated my consciousness. This allowed me to envision Nila, my protagonist, whose worldview is fractured by an acute sense of melancholy, both for the limits of her own life and for the world at large. We sold the novel in April of 2023, so all in all, it took three years to complete the book, though most of the writing happened in manic, intermittent outbursts. After Berlin I attended the Wallace Stegner fellowship as a poet, so I was writing poems on a weekly basis during that time as well—the novel was a secret project, which I nurtured on the side.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The book is concerned with several types of violence—the macroscopic, national, organized violence of neo-Nazis and the state versus the microscopic, domestic instances of violence within a nuclear family and a romantic partnership. I always knew that I wanted to end the book with an act of right-wing terror against Muslims that tears at the daily fabric of my characters, and therefore collapses the frail boundary between the private and public. The biggest challenge was to carve out a respectful way to write about the uncovering of the NSU, the German neo-Nazi underground terror cell, who were responsible for the murders of nine small business owners and one police officer. It was a fine balancing act to write about true events, while dramatizing the violence for the sake of fiction and yet trying to abstain from exploiting the tragic deaths of real people. Thus, it felt imperative to create a fictional climax to the murders—I invented the killing of the Qurbani brothers, with whom my main character, Nila, is familiar because they are part of her community back home.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I am a nocturnal writer, and writing is a secretive, mystical act to me. Ever since childhood, I have been most creatively uninhibited at night, after other people have gone to bed and the world gains a quiet and mysterious quality. For Good Girl, this night-time writing was extremely beneficial—although the book isn’t quiet, so much of the story takes place at night and in enclosed spaces such as clubs and apartments.

Most of my work begins in my iPhone notes or on my laptop while lying in bed or sitting on the couch. Once the vision for a project has taken shape, I can start writing at my desk like a normal person. At the moment I am experimenting with writing longhand for the first time in my life. The notebook and pen provide another level of intimacy with the blank page and force me to decelerate from the overcorrection that occurs while typing fast on the computer.

4. What are you reading right now?

The preparation for my next book includes a lot of research, as I’m writing about the 1970s and 1980s in Afghanistan, specifically the period under Soviet occupation. I am combing through government documents, archival photography and interviews, and several history books, including Invisible History: Afghanistan’s Untold Story (City Lights Publishers, 2009) by Paul Fitzgerald and Elizabeth Gould. I am also reading Pluto Press’s newly published volume of Ghassan Kanafani’s Selected Political Writings (2024), edited by Louis Brehony and Tahrir Hamdi.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

There are so many writers from the non-Anglophone world who deserve more recognition—Ghassan Kanafani, the Palestinian novelist and political writer, among them. Elias Khoury, who wrote Gate of the Sun (Archipelago Books, 2005), is still quite underread in the United States and in Europe. There is the Iranian poet and filmmaker Forugh Farrokhzad, who created incredible, politically charged work. I also highly recommend the work of the martyred Afghan poet Nadia Anjuman. She was part of the infamous Herati Golden Needle Sewing School, where women secretly studied literature under the strict patriarchy of the first Taliban government, which forbade women’s education. Anjuman was ultimately murdered by her husband in what could be considered an honor killing. A new edition of her poetry, translated by Diana Arterian and Marina Omar, will be published by World Poetry Books next year.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

This is a question my undergraduate students often bring up. I always answer the same way: only if it’s free. There are wide-ranging structural problems with the whole educational system in the U.S., but especially an MFA in creative writing is not worth incurring debt for, I believe, as long as there are so many wonderful programs across the country that offer full funding. Personally, I highly enjoyed my time at the NYU MFA—it was an incredibly transformative time for me. It’s an invaluable luxury to dedicate yourself solely to your writing practice for several years. You learn from accomplished professors, you read books you wouldn’t be otherwise exposed to, and you build a real community of like-minded people. But I am aware that I was lucky to have the funding and freedom to really focus on my writing without the burden of financial hardship. And I know, too, that many writers do well without one—craft can be taught, but the most important trait of a writer cannot be imparted in a classroom: You need to learn to really see the world. You need to look at, live inside, and care about the world; you need to let it change you. Eventually, one day, you will learn to see the world as text and see the text as a world.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

Both were instrumental in whipping the book into shape; both offered a symptomatic analysis of where the manuscript fell short in its early stages. My agent told me early on that we needed more background information about Nila’s upbringing, an aspect which I had been trying to avoid. Ultimately, writing into Nila’s childhood and familial context really unbolted the narrative arc and made me understand her motivations better. The childhood chapters were also some of the most exciting to write in terms of style, because I was more playful and experimental in them; some of those paragraphs really feel like prose poems to me.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Good Girl, what would you say?

Take your time. And indulge in the messiness, the privacy, the anxieties of the writing process. Nothing will feel as intimate or fulfilling as the phase where the book is just your own.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Good Girl?

The are two answers to this. One is more esoteric, about fostering my creative intuition and the world of my subconscious. Writing is an art, and I believe that fully immersing yourself in your project is the highest priority, so that your mind works on the book even when you’re not writing; I solved some of the most challenging problems while going on walks, while being at dinner with friends, at the movies, on vacation, and even during my sleep—I know this sounds ridiculous, but I dreamt entire chapters.

But the more pragmatic and obvious answer would point to the cultivation of a rigorous reading practice. I was obsessively reading through news articles, architecture books, propaganda pamphlets about neo-Nazis, blog entries, and memoirs on the Berlin techno scene. I also immersed myself in contemporary and canonical fiction, analyzing their plot points and structures, in order to teach myself how to write long-form prose. I had never attended a fiction workshop, so I didn’t exactly know how to craft a novel. I especially turned to the novels of James Baldwin, Jean Rhys, Marguerite Duras, and Shirley Hazzard for inspiration. They all portray exiled characters drifting through an urban landscape, and I see Nila as growing out of the tradition of flaneurs and flaneuses of their fiction. When I got tired of reading, I would watch films—Fatih Akin’s Head-On, Hou Hsiao–Hsien’s Millenium Mambo, Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides, and Agnès Varda’s Vagabond are films I would include in the bibliography of Good Girl.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Louise Glück once told me that living life well is as important as writing well—writing comes out of life. But I also cherish Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, which I often turn to when I feel blocked in my writing. He writes that one must regard one’s solitude as sacred, and that the past is an infinite fountain of inspiration: “And even if you found yourself in some prison, whose walls let in none of the world’s sounds—wouldn’t you still have your childhood, that jewel beyond all price, that treasure house of memories?” Yes, everyone can write, because everyone has had a childhood.